Harper Lee’s writing career was brief, but her single novel became one of the most famous in American history. To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) won the Pulitzer Prize, sold tens of millions of copies and remains a fixture of classrooms and popular memory. She published almost nothing else until Go Set a Watchman – an earlier draft of Mockingbird – appeared in 2015, just before her death and perhaps without her meaningful consent.

The Land of Sweet Forever gathers apprentice stories written before Mockingbird, along with a few later magazine pieces. Most are slight and the volume is more commercial than literary. Yet the early stories show Lee testing the voice and tensions that would define her later work: an insider’s affection for the South strained by growing awareness of its injustices.

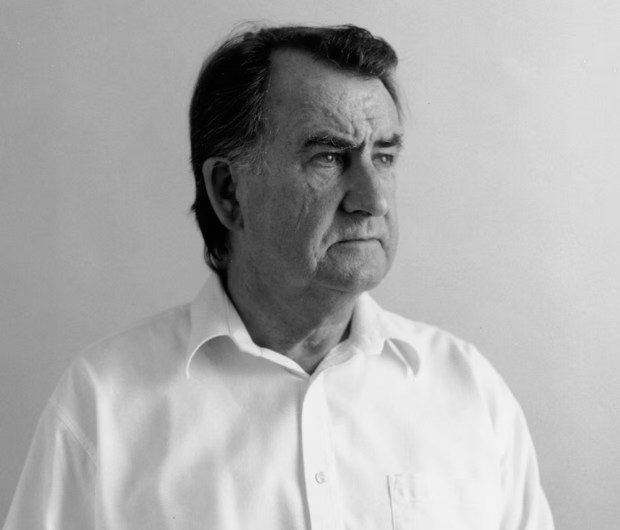

Harper Lee knew the world she came from, and she knew whatit cost to write about it honestly

Watchman was controversial because it revealed what Mockingbird had worked so hard to conceal: its Atticus Finch is an avowed segregationist and his adult daughter, Jean Louise, though calling herself ‘colour blind’, recoils at the idea of inter-racial marriage. The shock many readers felt in 2015 was like discovering an early draft of Nineteen Eighty-Four in which Orwell shrugs off mass surveillance. The limits of Mockingbird’s liberalism were suddenly clear. Yet those attitudes had always been present, softened by the novel’s sentimental humanism and its faith in the white saviour. Both books reflect the white South’s effort to reconcile inherited power with the language of liberal conscience.

Lee grew up in a culture where white respectability was its own moral currency. Class and race were tightly bound: status depended on lineage and on distancing oneself from the ‘poor whites’ who blurred the line between black and white in a segregated world. Respectable Southerners could see themselves as humane precisely because they drew that distinction – condemning racism in theory while preserving the hierarchies that sustained it.

The Land of Sweet Forever captures a young writer formed by those contradictions, trying to write past the world she would later critique. Several of these rediscovered stories contain the raw material of Mockingbird: the evasions of smalltown Alabama; the attempt to reconcile love for home with disgust at its prejudices. When Lee’s editor reshaped that conflict into Mockingbird, the result was a fable of decency for a nation eager to believe in its own virtue. These early sketches recover the harder story Lee struggled to tell – not innocence lost, but the ease of living with what one knows to be wrong.

‘The Cat’s Meow’ offers a study in strategic silence. The narrator returns to Maycomb to find that her sister, a ‘deep-water segregationist’, has hired an educated black gardener who is ‘not like any Negro you ever knew before’ – because he refuses to perform the expected deference. ‘You have to put him in his place occasionally,’ she adds, ‘but do it nicely.’ The narrator, now living in New York, literally bites her tongue: ‘The first lesson of living at home these days is if you don’t agree with what you hear, place your tongue between your teeth and bite hard.’ It’s an anatomy of liberal paralysis – knowing better, but giving in to get along.

That conflict runs through all of Lee’s work: the wish to be decent within an indecent order. Politeness becomes self-protection, dissent reduced to private disapproval. The result is not moral progress but the restoration of a genteel civility that turns prejudice into propriety and leaves the old order undisturbed.

In ‘The Water Tank’, perhaps the only story that stands on its own, a 12-year-old girl becomes convinced that she’s pregnant after an ambiguous encounter with a local boy. Ignorance, not guilt, drives her panic as she awaits punishment in a world where sex is never named. The story anticipates the sexual politics Lee would rework in Watchman and Mockingbird. In Watchman, a 14-year-old girl is impregnated by her father, and Atticus defends a black man accused of rape by arguing that the woman consented. By the time of Mockingbird, that material has transmuted into Mayella Ewell’s story – the abused daughter whose longing for tenderness condemns an innocent man. What begins in ‘The Water Tank’ as private fear ends, in Mockingbird, as moral fable.

What ultimately unites these works is Lee’s instinct toward accommodation – the drive to make peace with what she believes is wrong. Mockingbird translated that impulse into moral uplift, turning deference into civility and racial paternalism into virtue. Watchman stripped away the disguise, exposing the moral evasions such compromise required. That same tension shapes The Land of Sweet Forever, a collection so conflict-averse that most of its stories have no plot at all, collapsing into narrative drift, rehearsing the art of looking away. Lee knew the world she came from, and she knew what it cost to write about it honestly. These stories bear that pressure: the urge to preserve a vanishing South and the equal need to protect its self-image by smoothing away its cruelties. In the end, she could not afford the candour her subjects demanded.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.