It’s over for Sussan Ley, apparently. Don’t even be guided by the polls. Just sound out her own parliamentary party room: the question is not if she should go but when. Her party abounds with colleagues wielding knives and waiting to sink them between her shoulder blades.

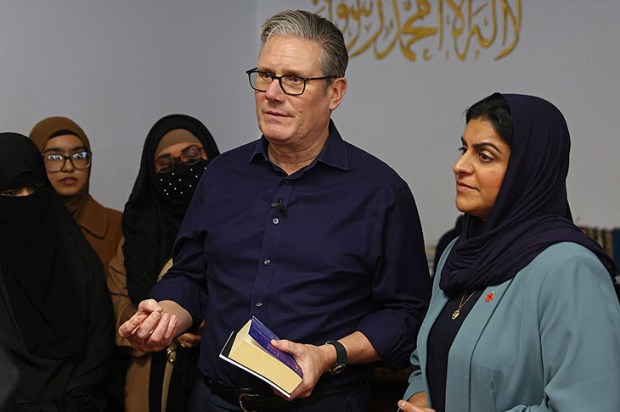

What Andrew Neil says of Keir Starmer, which you can read in the UK Daily Mail, could be said of Ley: there will be no comeback, no resurgence, no clawing back of support bit by bit. The Libs have plumbed the depths too deeply for any kind of renaissance to be realistic.

Yet despite the predictions of disaster – or perhaps even because of them – Ley ended up having a good week. The Liberals are now developing some firm policies on energy and immigration. Initially ridiculed, Ley now looks honest, serious and determined. Witness her many television and radio interviews where she was subjected to the most intense scrutiny, and she answered all questions with aplomb. Even her sceptics have come to respect the persistence of a patently decent woman trying to do one of the worst jobs in Australia.

The sophisticates scoff at her decision to jettison net zero, but the public will share her view about the sheer absurdity of the government’s unaffordable and unreliable energy plans, especially given that governments across the globe are walking back climate goals they made years ago.

Ley’s courage and stoicism remain admirable in her battle to wean the nation off a renewables-first policy. If she can now offer equally sound statements on where her party stands on other great issues – from taxes and spending to schools outcomes and identity politics – she will find people at last returning to the Liberals.

Besides, as if we need reminding, political assassinations rarely end well. Since the Australian people retired John Howard, both major political parties have had a dozen leaders: seven for the Libs, five for the ALP. For a dozen years, from 2010 to 2022, we experienced seven prime ministerships: Kevin Rudd (2007-10), Julia Gillard (2010-13), Rudd (2013), Tony Abbott (2013-15), Malcolm Turnbull (2015-18), Scott Morrison (2018-22), and Anthony Albanese (2022-). Four of them were sliced and diced by their colleagues, their assassins egged on by a bloodthirsty press gallery.

It’s only recently that Australian politics have returned to any sense of normality. Albo’s thumping election victory in May marked the first time a prime minister has been re-elected since 2004. But our political discourse was so badly damaged during 2010-22 that one wonders why knife a leader six months after the last leadership transition.

Have we forgotten that night in June 2010 when Labor’s powerful factional chiefs told Gillard to, in Macbeth parlance, knife King Duncan? Like many such gambits, this one ended badly for the assassins. The conspirators fatally stabbed someone they loathed (Rudd), but in the process sparked a cycle of revenge knifings in the form of damaging leaks that culminated in a disastrous election result.

These days, Gillard is lionised as something of an elder statesman. So it’s easy to forget that in office, from 2010-13, her credibility drained away as if from an open wound. At the same time, the spectre of Rudd haunted parliament: he rose from the political grave and pursued his nemesis so effectively as to make even a ghostly Banquo proud. That did not end well for Labor or the nation.

Have we also forgotten the disastrous Turnbull experiment? Abbott sank Rudd in a general election – and, in power, repealed the widely unpopular carbon tax and restored sovereignty to our nation’s borders. Ultimately, though, he was also living on borrowed time. Within 18 months, his colleagues had enjoyed the ecstasy of their landslide election victory followed by the agony of feeling doomed.

Talk of a leadership bid was encouraged. And it was (of all people) Turnbull who emerged as Abbott’s assassin, something no one would have foreseen six years earlier, in 2009, when Abbott (thankfully) overthrew him as opposition leader. But it was not long before Turnbull came to resemble what the aforesaid Andrew Neil says about today’s beleaguered British prime minister: that ‘he isn’t just useless at politics (they rumbled that a while back), he is useless at government, which becomes all the more apparent with every passing week.’

The lesson here is clear: defenestrating an unpopular party leader may feel cathartic: the plotters might be relieved at ending a rush of bad polls. But any successor would likely face the same problems, and there could be vendettas, smears and reprisals.

For now, Ley’s critics have been seen off. She has taken one monster pummelling after another: the resignations from her shadow cabinet ministers and the debacles of question time. No professional boxer has taken such a beating and come back for more.

Ley is denounced for being in cahoots with wets. As an experienced parliamentarian – she’s been an MP three years longer than the youngest MP (Charlotte Walker) as has been alive – Ley is the first to recognise that the Liberal party has always been a grand coalition between rival interests: town and regions, right and left, conservative and moderate. The task of any party leader is to strike a balance between rival factions of the party.

The challenge now is to find all the discipline, talent and energy she and her team can muster, to seize the imagination and win the trust of the Australian people. It’s time her underlings stopped playing games and got behind her.

Because if any internecine struggle within the Liberal parliamentary party erupts into a political bloodbath, the biggest loser won’t be Ley or even the Coalition itself. Instead, it will be the general public – deprived of the chance of an opposition to hold a wayward government in check during these desperately difficult times.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Tom Switzer is author of ‘Events, Dear Boy: Any Government Can Be Derailed’ (Centre for Independent Studies.) https://www.cis.org.au/publication/events-dear-boy-any-government-can-be-derailed/

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.