‘What we need is a governor-general!’

This was the angry outburst of an American to an Australian journalist when she was frustrated by one of those recurring US government shutdowns.

The current one is the longest in history, with a Democrat insider reported to have threatened that ‘short of planes falling out of the sky’ the government would not be reopened. The claim that poor children are not getting the food they need, or are even being starved, is apparently not enough.

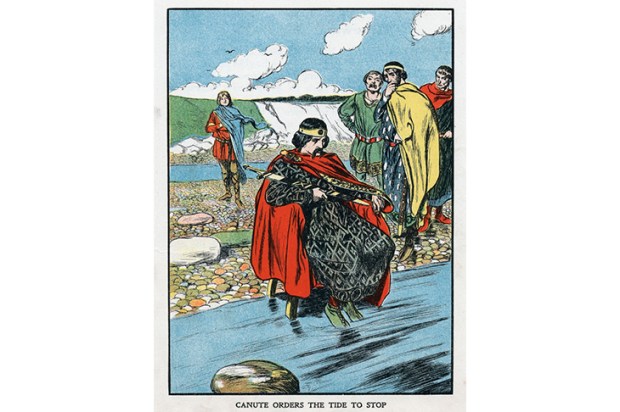

Little wonder that President Trump is calling on a reluctant Republican Senate establishment to end the filibuster rule that requires a 60-per-cent majority for budget approval. That should remind soi-disant Australian republicans to think twice before insisting on scrapping the one part of our constitution that saved Australia from a threatened long-term shutdown in 1975 -1976.

On that I was interested to see the eminent constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey’s assessment of the law surrounding the 1975 dismissal of prime minister E.G. Whitlam, with which I agree, and her report about Sir John Kerr’s genuine concern, based on his own childhood poverty, about those who would suffer from any extended shutdown.

That the poor would suffer from their action was hardly prominent on the list of concerns of either protagonist, neither Gough Whitlam nor Malcolm Fraser.

For the sole purpose of demonstrating the independence of her judgment, I should point out that while Professor Twomey is a leading authority on the existing monarchy’s powers, the fact that she has proposed a replacement republican model for Australia is a reasonable indication of her position as a republican.

With Remembrance Day 2025 marking the 50th anniversary of the dismissal of the Whitlam government, much of the media recollection seems to constitute a rehabilitation of the failed Whitlam government.

Much is made of the ‘reforms’ of that government. This involves classifying every change, including those deemed unworkable by subsequent Labor governments, as a reform. This is lazy reporting, acting as the propaganda arm of a long-gone government.

The Whitlam government made many changes, but the number which could really be classified as true improvements is minimal. Apart from the Trade Practices Act, it is difficult to think of a real reform.

Making something free, that is requiring some taxpayers to pay for someone else’s advantage, is not in itself a reform.

In foreign policy, lending moral support to a debauched government responsible for the deaths of millions of its own citizens through starvation and murder is not a great achievement.

Much better to let the people overthrow that monstrosity.

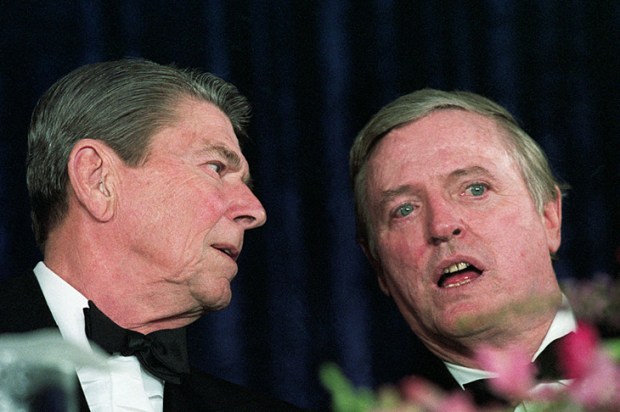

Reflecting back on that period, in many ways it seems to have centred on an Olympian struggle between Whitlam and Fraser, with the finding of a way to avoid the disaster of a government shutdown or worse dependent on the wisdom and courage of another Olympian, a better Australian than either, Sir John Kerr

While I will never forget first seeing Sir John, a large and impressive man with almost ornate flowing grey hair, wearing a black coat, winged collar and grey striped pants striding down Sydney’s Phillip Street, Whitlam was by far the more charismatic.

And as former prime minister John Howard recently observed, Whitlam was also probably the most impressive parliamentarian of the time; that is, he was a master of parliamentary process and procedure.

That is why it is so surprising how much he failed in that parliamentary process when it mattered most for him on 11 November 1975.

As the driver of the events which culminated on that day, Whitlam was endowed with great theatrical ability and style, and a personal confidence that he was always right.

He believed he was right, even if the change he proposed destroyed something which worked well, such as the then health system, which centred on mutual societies which had been so successful in such areas as health and insurance.

He believed he was right even when he radically changed his mind.

The prime example of that was when he ensured Labor would regularly vote against a government money bill in the Senate. He was so proud of this strategy that on the 170th occasion he had Senator Lionel Murphy table in the Senate a list of the preceding 169 occasions. The purpose always, Whitlam declared, was to destroy the government. An election must follow.

He followed this when he was prime minister and the opposition moved against him in 1973.

With Whitlam winning the resulting election, absent undefined ‘reprehensible circumstances’, Fraser forswore any move to force an early election.

Meanwhile, Whitlam informed the parliament that the extraordinary proposal to take over all of Australia’s mining and energy projects by buying them back through massive loans negotiated through a Pakistani commodities broker,Tirath Khemlani, authorised behind the back of the governor-general and although obviously long-term, designated short-term to avoid the need for long-term approval, had been abandoned.

When it was demonstrated the loans were still being sought, and although Whitlam denied knowledge of this, Fraser declared this to constitute the reprehensible circumstances which would justify the withholding of supply until an election was called.

What Whitlam did then was certainly reprehensible.

Knowing that he had no constitutional alternative but to advise a general election, he tried everything improper, devious and unconstitutional to cling to power.

As Peter O’Brien details in his excellent book, Villain or Victim, Whitlam’s apologists even now defame Kerr for something he did not do and which Fraser agreed he did not do, at least until 1987.

This was to tip off Fraser that Whitlam would be dismissed. Strong evidence indicates his call to Fraser was strictly limited to whether he would still block supply.

If a prime minister again tries to cling unconstitutionally to power, let us hope the then governor-general has the same sense of duty and courage to do what Kerr did.