Recently I delivered the Neville Bonner Oration at the 26th National Conference of Australians for a Constitutional Monarchy (ACM). My address was titled ‘A Tribute to Sir John Kerr – an Australian Hero’.

Included in the conference agenda was an interview of former prime minister John Howard, by Professor David Flint. In response to an assertion by Mr Howard that he thought it unlikely that an Australian republic would be on the agenda anytime soon, Professor Flint asked if there was then a continuing role for the ACM? Mr Howard said words to the effect of, ‘Yes, you can never be sure of anything.’

To that I would add that the need for an organisation like the ACM has never been more evident, because a republic is not the only threat to our constitutional monarchy.

It may not be explicitly replaced any time soon, but it can, indeed has, been undermined by a number of factors, including increased judicial activism and an appalling level of misunderstanding of our constitution.

This latter has been fuelled by a determined campaign to undermine the reserve powers of the Crown that are exercised when necessary by the governor-general. This has manifested itself in the lengths that certain ‘historians’ have gone to in order to make Sir John Kerr the Emmanuel Goldstein of Australia. The campaign reached absurd heights on this the 50th anniversary of the date on which Sir John Kerr resolved an intractable political impasse by sacking a prime minister who could not secure supply to the Crown and replacing him with one who could and did. One of the aims of this campaign has been, in my view, to indoctrinate/intimidate governors-general against the use of the reserve powers.

In perspective, the events of 1975 were controversial at the time, but the outcome was a peaceful transition from a dysfunctional parliament to a parliament which was able to provide an effective government.

My purpose here is to clarify some aspects of our constitutional arrangements. Let me begin with the claim that Kerr undermined our democracy by sacking an elected government. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of our constitutional arrangements. Conversationally we say we elect a government but, technically, we do not. We elect a parliament.

The governor-general appoints a government from within the ranks of that parliament.

Section 64 of the constitution provides that the governor general appoints ministers and that they hold office at his pleasure. Under normal circumstances it makes sense for the governor-general to appoint a government from the ranks of that party which holds a majority of seats in the House of Representatives because it is they who have the capability to implement a legislative agenda. But this is a common-sense convention. It is not a constitutional requirement.

Whitlam’s position as prime minister was not guaranteed him by being elected. That merely gave him the right to claim appointment. Understanding this fine distinction is essential to making sense of what happened in 1975.

The second concept not clearly understood is that ‘The Governor-General acts on only the advice of his/her Ministers’. That simply means that the governor-general cannot sign an instrument of executive government on his/her own account. He/she is entitled to seek legal advice as to the legality of any instrument put before him. Normally that advice would come from the attorney-general and/or the solicitor-general. If the governor-general seeks advice of this nature, as Sir John Kerr did on a number of occasions, and if he is doubtful or unsatisfied with that advice, his normal course of action would be to accept that advice and let the courts decide the matter. As Kerr did in the matter of the Executive Council minute approving the Khemlani loan. The fact that Kerr sought such advice, constituted a tacit warning to the government.

Importantly, the governor-general is not proscribed from seeking independent legal opinion on a matter related to the exercise of the reserve powers. If a proposed exercise of a reserve power is adverse to the interests of the incumbent government, such as withdrawing the commission of a prime minister, then it would not make sense for him to rely on the advice provided him by the government. In fact, Kerr sought advice on a legal opinion issued by shadow attorney-general Bob Ellicott that the circumstances prevailing at the time imposed a duty on the governor general to act immediately to replace the government. That he sought such advice should have served as a warning to Whitlam that dismissal was on the cards. In the event Kerr never received the requested advice. He was certainly entitled to seek separate advice from the chief justice. And there are numerous precedents for this.

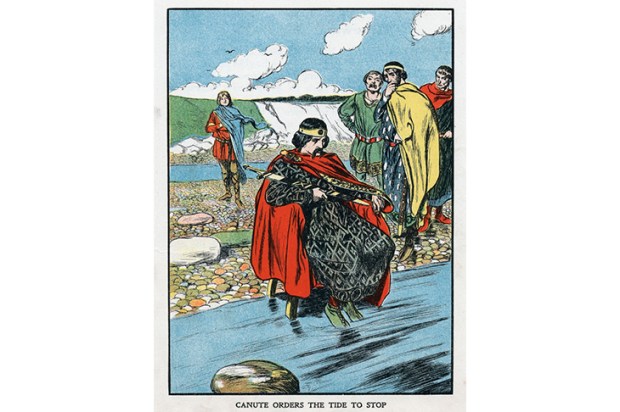

Our Westminster system derives from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which established the supremacy of parliament over the Crown and limited the power of the monarch. That was aimed to prevent a monarchical tyranny. But now that – as far as executive government is concerned e.g. raising taxes and spending money – parliament has all the power, what safeguards do we have against a parliamentary tyranny? As arguably exists in Victoria.

The obvious answer is the judicature. But if the judicature is now corrupted by activism to the extent argued by Professor James Allen, as a last line of defence we may have need of the reserve powers and a governor-general prepared to use them.

Let me give you an example of what a parliamentary tyranny looks like.

What if the governor-general were confronted with a monstrous piece of legislation such as the recently enacted Victorian treaty?

Intuitively it seems to me it may be unconstitutional. It gives to Aborigines in Victoria rights additional to those of ordinary Australians and moreover, which are not available to Aborigines in other states.

It certainly offends against the principle of equality before the law.

And, in its preamble, it tacitly concedes to Aborigines a separate form of sovereignty adverse to the Crown.

Regardless of that, it is highly destructive public policy that flies in the face of the emphatic rejection of the proposed Voice, even in Victoria. And this Bill goes considerably further than Albanese’s doomed project.

If I were a governor-general confronted with such a Bill, I would invoke one of the reserve powers and would refuse royal assent, certainly, until the public acceptance of it were confirmed by a plebiscite.

The constitution explicitly gives the governor-general that power, and it imposes no conditions upon its exercise. I accept that that is a big call. I accept that is very rarely done. It would not be done lightly. But we must not rule out the possibility that it may be justified in some circumstances.

As a traditional civil society, we live in troubling times. We do not need a diffident governor-general. We do not need a meddling governor-general. But now, more than ever, we need a governor-general prepared to be assertive when the occasion demands.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.