There is a certain kind of politics that does better in Bellevue Hill than it does in Goulburn. It is the politics of curated virtue: the belief that with the right tone, the right palette, the right language of ‘community’ and ‘listening’, public life can be elevated above conflict and questions of distributional fairness. In 2022, this aesthetic became a movement. Climate 200 presented itself as gentle and neighbourly, a non-partisan restoration of decency. A kind of Whole Foods wrapped in Scanlan & Theodore. Yet in practice it was financed by billionaires, professionally messaged, centrally polled and targeted with great precision at the electorates most receptive to abstraction and piety.

Simon Holmes à Court never arrived on the scene as a dispassionate policy thinker. He emerged as a Twitter combatant – a man who treated politics as moral sorting. His persona was on display from the beginning: sanctimony personified. He aligned with the enlightened over the backward, the virtuous over the compromised. His case for renewables rested not only on values, but on certainty. He told us repeatedly, incessantly, that ‘renewables are now the cheapest form of electricity’ (while citing GenCost charts which neglected enormous additional system-wide costs), and that concerns about grid stability, dispatchability or the impact on farmers and rural communities were simply ‘distractions used by climate laggards’.

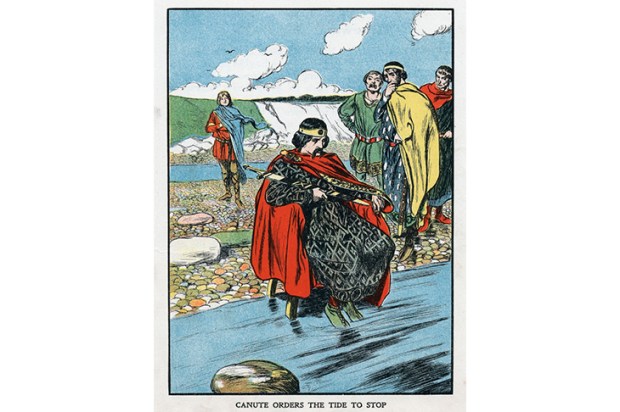

He presented himself as the custodian of the rational position – the adult in the room, the man explaining the obvious to those too blinkered to see it. Yet he has never been an expert in energy economics, grid engineering, synchronisation, transmission, or the financial mechanics of electricity systems. No, the transition would be simple because it was righteous.

After nearly a decade on the scene his impulses were scaled and branded. Climate 200 nailed the narrative of grass-roots revival, but operated as a political machine. Its candidates were independent in name, yet unified in message, style, posture and purpose. The emotional architecture was familiar: a single class of people who ‘get it’, an opposing class cast as morally compromised, and a leading figure who in his subsequent manifesto of self-congratulation would style himself as The Big Teal.

The Teal movement sponsored by him resembled the populist movements it claimed to oppose. Where American populism was brash and triumphant, this Australian variant was urbane and superior. Both depended on big money and colour and movement. Both used populist slogans and mercilessly attacked their villains.

But the chickens are coming home to roost. Labor’s climate overreach has been enabled and legitimised by Climate 200 and the Teals – with The Big Teal often the lead character in the national debate – playing on its left flank. For the nation-changing target of 82-per-cent renewables, the complexities are now impossible to ignore. The physics of stabilising a grid across continental distances, the real cost of firming intermittent generation, and the sheer land and capital intensity required to build thousands of small energy factories across our ancient landscapes – plainly obvious difficulties farmers grasped from the outset – are now visible to everyone. With dispatchable capacity declining faster than replacement is being built, and organised revolt across regional Australia, the scale of the misjudgment is now exposed.

The slogan ‘renewables are cheaper’ was electorally powerful because it allowed voters to feel virtuous at no cost and scorn those who queried it. But slogans are not systems. As Oxford Professor Dieter Helm has made clear, intermittency is not free, transmission is not neutral, and backup is not optional. Helm wrote yet again this month what farmers have said for years: the more intermittent generation one builds, the more expensive and infrastructure-heavy the system becomes. This transition is land-hungry, capital-intensive and socially fracturing. The fracturing occurs elsewhere – amongst provincials who are expected to roll over and take one for the country.

The irony is unavoidable. The need to hasten carefully – to secure social licence, to confront questions of fairness, and above all to ensure that decarbonisation does not impose unsustainable costs – is now being acknowledged across the world. Our own now-not-so-merry band of energy technocrats concede these are the points at which the transition is failing.

Even Bill Gates, long a champion of rapid climate action, has now stressed that climate change will not end civilisation and that the transition must succeed without driving energy prices beyond what communities will accept.

Electricity prices have risen sharply. Regional Australia is in open revolt. Projects and transmission corridors have become political battlegrounds. As the rollout becomes more authoritarian social licence is not just eroding – it has vanished. Even in Teal heartland, the tone has shifted. The polo set who live in Bellevue Hill but spend weekends stick-and-balling at Goulburn and Scone have seen the turbine ridgelines, the seas of panels and heard about the corridors of monstrous towers now set to pass through some of our best farming country. Young renters in Bondi have seen their electricity bills. The distance that once separated the virtue from the cost is closing.

The wise elders of Australia’s decarbonisation club are alarmed. Rod Sims, former ACCC chair, warns the transition risks becoming ‘politically unsustainable’ because the costs are falling so unevenly. Ross Garnaut has said recently that scaling up subsidies for wind and solar ‘won’t get Australia to its targets’ and risks ‘buying failure’.

All the while we’re told it’s only just getting started.

All of this explains the shrill tone of Holmes à Court’s piece in the Australian last week. The most striking feature was the omission: gone was any claim that electricity obtained from the wind and the sun would be cheaper. He would be alarmed more than anyone that the rules of the game have changed. Donation cap laws have removed Climate 200’s central strategic advantage: the ability to purchase feel-good emotion. More than halving the $2 million spends in inner-city seats will require the Teals to do something they’ve not had to do before: make the case for their version of the transition based on actual evidence.

The slogans from 2022 will need to change, because the moment of madness has gone. The country has seen the bill and is starting to feel the consequences. The Big Teal may hanker for a return to centre stage – but this time he’s set to be the villain playing the Big Denier.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.