Whether you went with the two big rugby goalposts, those opposing H’s of Heaney and Hughes, or with Blake Morrison’s quondam super league of world English (or sometimes airport) poets, Brodsky, Walcott, Murray and Heaney, Heaney loomed amiably in the poetry landscape of the late 20th century. I knew him a little and liked him a lot. Enough now to appreciate that there was something endlessly consoling about being alive at the same time as an incontestably – or only rarely, foolishly contested – great, canonical poet, someone you might occasionally meet or, more regularly, see new poems or new books by; and something correspondingly harrowing and disorientating about this same poet no longer being alive. A geographical feature has been taken away, a hill, a forest, a river. Things look a little despoiled. A little pointless.

Towards the end of his life, and still more afterwards, the living succession of ‘slim volumes’ – and Heaney was a model of productiveness, books every three to five years, without fail – found itself replaced by bigger, bulkier, less useful, less original, less ‘speaking’ compendiums. (An exception is the truly priceless and sui generis book of conversations with Dennis O’Driscoll called Stepping Stones.) Each one somehow monumental. Big productions, all. So many tombstones, if not cenotaphs. There was Opened Ground: Poems 1966-96, that came out in the wake of the 1995 Nobel Prize; the Collected Prose,that bundled up his various lectures and essays; last year’s Collected Translations; the Letters; and no doubt Fintan O’Toole’s promised biography as well. And while we wait for that, there is this: The Poems of Seamus Heaney, a volume that includes some 600 pages of scholarly apparatus and introduction, the title making it sound almost like a critical work, a book about, rather than a book of.

Not that long ago in the scheme of things – the occasion was the publication of John Berryman’s Collected Poems in 1990 – I wrote something along the lines of ‘the collected poems of a modern poet should not have an academic turnstile put in front of them’. While the present production is nowhere as vaunting and foolish as that was, there is still something about it that puzzles me, dismays me a little, even though I understand what brought it about: a helplessness, a strickenness, a wish to dignify, even a form of mourning behaviour. There is a need to be seen to be adding value, a desire to find information to share and catch it while it’s new. I would suggest the opposing argument is at least equally true: the best thing one can do for a recently living great poet is nothing. Nothing but the poems and some white space in a binding.

As wild beasts are now for the most part seen in zoos, to the extent that we can imagine them in no other habitat, I suppose there is no stopping the movement of poetry into the doubtful shelter of the academy. It can even be argued that there is something right about it in this instance, given that the way Heaney’s poems entered most readers’ lives will have been as set texts for O- and A-Level.

Anyway, this is what we have, how-ever impractical and cumbrous and best not approached without a friendly lectern to hand. And at this point I double back on myself again, feel I have been churlish and ungrateful, because there is really so much interest and help in the little essays on the individual books and the detailed notes on the circumstances and contents of the poems, and even on individual words (all these modestly tucked away at the back). Is it really any worse than going around a museum with an audio guide (something else I don’t do)?

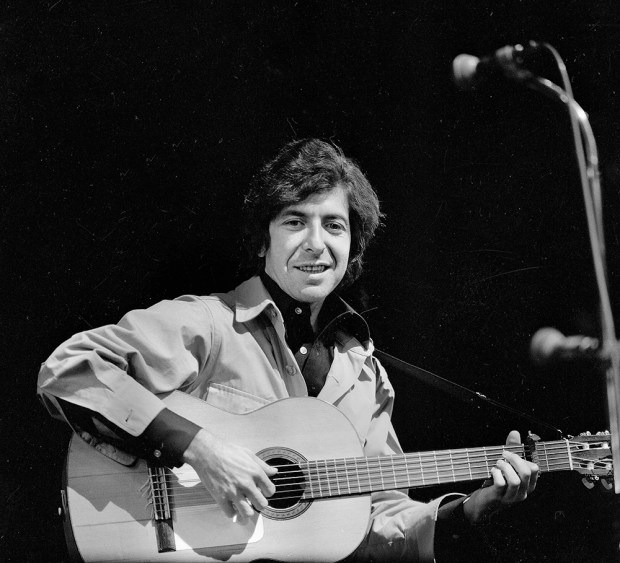

Heaney’s reputation crossed the Irish Sea, but the man himself somehow never left or changed his being

But even beyond that, it just feels right, it feels majestic, to have everything, all the poems, together. For upwards of half a century, it truly was ‘one life, one writing’. Especially with Heaney, whose work seems so especially centred and concentrated, so autochthonous, so immune to fashion and trend and chance, so devoid of false notes and missteps, without digressions and dependencies and failures. From the awed consciousness of the boy (‘By God, the old man could handle a spade./ Just like his old man’) to the memories of one who had become old himself (‘Next thing he spoke and I nearly said I loved him’): of parents and family and farm and village; to leaving home to study, and be offered alienation (which he refused); then love and marriage and a family of his own; to an ever-deepening awareness of riven, troubled Ireland; to his quiet refusal to let himself be instrumentalised. His reputation crossed the Irish Sea and then the Atlantic, but the man himself somehow never left or changed his being; he only grew. Here was one poet who really never lost himself or became corrupted or distracted: ‘The deal table where he wrote, so small and plain,/ the single bed a dream of discipline’. (Yes, he wrote it of Thomas Hardy, but it might as well have been himself.)

The voice was frequently encumbered (‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’), then later, notably un-, or better dis-encumbered (‘Do not waver/ Into language. Do not waver in it’). It seemed to reach, like the rippling geometries increasingly identified in the poems, all distant parts equally. It remained, as it was sometimes forced to protest, Irish, all the while encompassing and eclipsing English, and acquiring something Mediterranean as well, through the long engagement with Dante and with Virgil. (When he borrowed, he never took, he only gave.) An initial orientation to earth and water (‘The bogholes might be Atlantic/ seepage./ The wet centre is bottomless’) shifted upwards and outwards to air and light, though maybe never to fire. It perhaps seems fortuitous that, during Heaney’s lifetime, Ireland opened and found some sort of peace; I don’t believe it is. ‘The end of art,’ Heaney wrote, ‘is peace.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.