To our jaded century, ‘fairy’ carries connotations ranging from the sentimental to the sickly. It conjures childishness, foolishness, insipidity and softness – Tinker Bell, the Tooth Fairy, the Cottingley photographs that fooled Arthur Conan Doyle, cakes, twinkling lights and a certain brand of soap. Francis Young feels that the word should also be applied to countless other traditions of supernatural entities from earliest times on – that fairy stories help us fathom being human.

Young has written or worked on many books about religion and folklore, and this is his third specifically on fairies. Suffolk Fairylore (2018) and Twilight of the Godlings (2023) explored British ‘encounters’; now he expands across Europe, with a chapter-length foray following fairies carried as cultural cargo by Europeans during the ages of discovery and empire. He enjoys an intimate acquaintance with Old World eeriness, and evinces sophisticated understandings of the contradictory ways Christianity has handled vernacular beliefs in entities other than angels and demons. He is rigorous, yet respectful of ‘old believers’ of all ages and faiths. It is, he reminds us, arrogant to treat Christianity with academic seriousness yet scorn equally plausible or at least sincere folk beliefs.

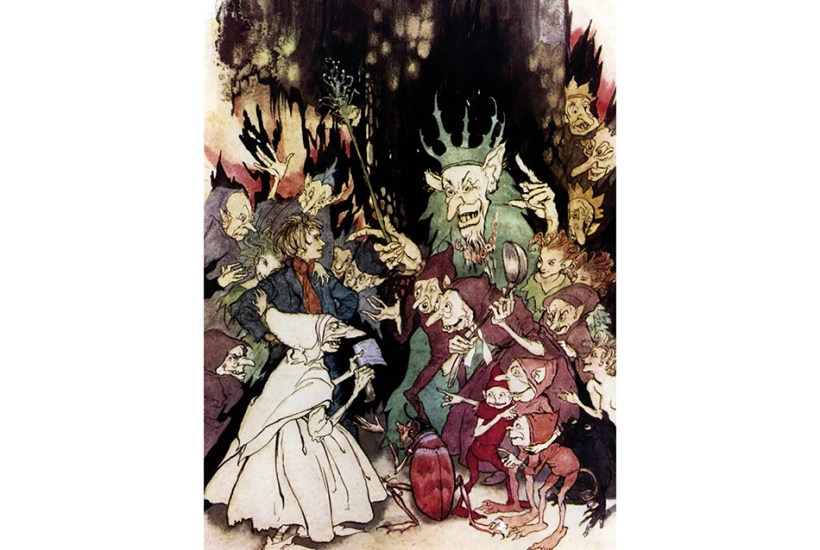

Fairies are protean. They are the diminutive, winged females of cartoons and children’s books, but they can equally be boggarts, brownies, dwarfs, fays, gnomes, goblins, kobolds, leprechauns, poltergeists and much else. They can be beautiful or ugly, tall or tiny, friendly or terrifying. They can guard a house, or a land, or a treasure – or lead us astray, trap us in their kingdoms and steal our babies. They can cause incurable diseases through the dreaded ‘fairy blast’ or cobble us shoes. Unpredictability is almost their defining characteristic, so they were often referred to, euphemistically to avoid provocation, as ‘the fair folk’, ‘the good neighbours’ or ‘the gentry’.

Though fairies could be strange, they could also be akin – with many stories about sexual liaisons, but also mirroring our social orders, and often Christian (or wishing to be). Elizabeth I was Spenser’s ‘Faerie Queen’, and even the witch-obsessed James I enjoyed court masques featuring unbiblical winged sprites. Shakespeare’s Puck acted as emanation of Arden, and so all-enchanted England; in 1942’s The Little Grey Men, ‘BB’ (Denys Watkins-Pitchford) enthused that Warwickshire was one of the last English counties where one might meet fairies. In Richard Dadd’s 1864 painting ‘The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke’, the pocket-size beings watching the Feller raise his axe resemble otherwise everyday Englishmen and women, caught in the rich vegetation of their nation’s understorey. Fairies have even been conceived as autochthonous racial stocks – marginalised peoples deriving from half-forgotten histories – and so a metaphor for national decline. For the poor, spirit beings were allies whose assistance might be obtained; they also offered otherworldly authority to offset oppressive real rulers.

‘Unreal’ entities have been historically omnipresent, linked to landscape features, natural phenomena such as ‘fairy rings’, artefacts such as ‘elfshot’ (prehistoric arrowheads), mystical reveries and inexplicable time-slips. The Greeks had their dryads and nereids; the Romans their lares and penates; Slavs their vilas; Norwegians their trolls; and the English their pucks – only becoming ‘fairies’ after the 15th century, courtesy of French romances. In some countries – Iceland, Ireland and Lithuania – folk beliefs in fairies are particularly resilient, but they have been, and can be, found anywhere. Even the most materialistic eras threw up influential fairy believers and those who thought seriously on the subject, from John Aubrey to J.R.R. Tolkien. Napoleon swore he had met a sprite called the Little Red Man of Destiny. Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, of Battle of Britain fame, later feared war between fairies, goblins and humans.

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding feared war between fairies, goblins and humans

There are fascinating connections with pre-Christian animistic and therianthropic ‘godlings’, Near Eastern spirit beings, medieval ‘wild men’, Renaissance occultism, early modern antiquarianism, 19th-century folklore studies, ghost stories, spiritualism, modern ufology, cryptozoology and neo-paganism. The hardest sciences are sprinkled with fairy dust, as suggested by entomologists’ choice of ‘larva’ (Latin for ‘ghost’ or ‘goblin’) to describe insect young, and ‘uncanny valley’ to express the unease aroused by AI humanoids. Fairies unfailingly update themselves, as ‘evidenced’ in September 1979, when children in Nottingham described being chased by gnomes driving cars.

There was a melancholic late medieval notion that the fairies were departing from an increasingly unmagical world, expressed by the Wife of Bath – ‘But now kan no man se none elves mo’ (but now no man can see any more elves). This resonated with Tolkien, whose elves were doomed to be succeeded by duller mortals, and resonates today in a world longing for re-enchantment. But, as Katharine Briggs noted reassuringly in The Vanishing People (1978), the fairies are ‘always going, never gone’. They have survived contempt, demonisation and Disneyfication, and are now attracting thinkers interested in imaginative ecology, fantasy LARPing, liminality and neurodivergency. Fairies, we find, have had a fantastical past, and seem destined for a fabulous future.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.