There is a moment in Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall which has been much on my mind lately. It is the bit towards the very end of the novel when our hero, Paul Pennyfeather, re-encounters the sinister modernist architect Professor Otto Silenus. By this point Pennyfeather has undergone all manner of travails. He has been debagged and sent down from Oxford, accused of human-trafficking and sent to prison. But, as the pair sit outside the Corfu villa in which Pennyfeather is staying, the professor suddenly offers to reveal his theory about the meaning of life.

How many people in politics have been picked up and flung off this great revolving fairground ride?

Silenus describes a particular fairground attraction, the Devil’s Wheel (‘the big wheel at Luna Park’). For five francs the public can go into a room with tiers of seats. At the centre is a great revolving floor which spins around fast. People try to clamber up the revolving floor and get to the centre of the wheel. How everyone laughs as they see other players get flung off. How they whoop and holler as they get similarly flung around and fail in their climb.

‘I don’t think that sounds very much like life,’ said Paul rather sadly.

‘Oh, but it is, though,’ [replied Silenus.] ‘You see, the nearer you can get to the hub of the wheel the slower it is moving and the easier it is to stay on. There’s generally someone in the centre who stands up and sometimes does a sort of dance. Often he’s paid by the management, though, or, at any rate, he’s allowed in free. Of course at the very centre there’s a point completely at rest, if one could only find it.’

In recent years I have thought of this passage often while observing British politics. The whooping, laughter and falls seem to have become almost part of the purpose of things. For the press and other participants, they seem to provide a meaning of a kind.

Remember when we thought we couldn’t be worse run than we were under Theresa May? Remember how, having got rid of her, we had the great dawn of Boris Johnson? Remember how that devolved into a great row about a cake and booze and eventually some completely unknown Tory MP touching someone’s bum and the whole government collapsing? Remember the hours of Liz Truss and the rain-soaked end of Rishi Sunak? Next the great dawn of Keir Starmer, and now perhaps the end of that too. How many people in politics have been picked up and flung off this great revolving fairground ride in the past decade?

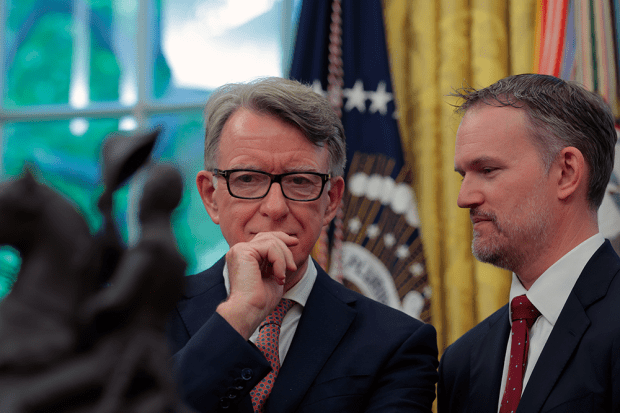

I can’t deny that there isn’t a certain fascination to it all. If Labour is mad enough to turf out Keir Starmer I suppose we might get Angela Rayner as prime minister, or conceivably see Ed Miliband enter Downing Street. Perhaps even this Labour party would blush at that switcheroo, vote for Christmas and we could then watch most of them get thrown off the wheel in their turn. Certainly there would be a sort of pleasure in watching this. As there was this week when Wes Streeting – who seems to imagine he could be prime minister – released all of his private text messages with Peter Mandelson, apparently in an effort to slow the wheel down, with the result that he merely sped it up.

I suppose the one consolation that the players have in this country is that our particular fairground ride is not as lethal as it is in other places.

News came through last week of the death of Saif Gaddafi, son of the late and unlamented Libyan leader. He appears to have been murdered by a rival faction in the north-west of the country. Personally I was rather surprised to learn he was alive at all. Some years ago, amid the Gaddafis’ crackdown on the Arab uprising, Saif decided to join his father in fighting to the last bullet to keep his family in power. His father then met a distinctly sticky end at the hands of a mob and a knife. Saif turned out to have been captured somewhere in the south. After a time he was reported to have re-emerged with a few fingers missing, with his captors saying something about frostbite in the desert. It seemed rather more likely they had caused the falling-off during some interrogation procedure.

All of which brings another memory to mind – that time in the late 2000s when a whole bunch of people in the UK tried to bring the Gaddafis in from the cold. The London School of Economics awarded Saif a PhD which had clearly been written for him. The university’s then leadership accepted a seven-figure donation from the family, with those of us who criticised it being breezily dismissed. LSE even invited Colonel Gaddafi to give a guest lecture via video-link.

The fawning-ness of the students was quite something to behold. If the guest lecturer had been a Republican leader from Washington D.C. there would have been nothing but protests and heckling. But this was merely the butcher of Lockerbie and so, after a slavish introduction from faculty, the nice students asked the Colonel hardball questions like: ‘Where do you see Libya´s place in the world?’ A question I will forever be grateful for, because – after a pause – he replied through a translator, ‘Libya is in north Africa’, showing that perhaps the only person to rate that crop of students lower than I did was a dictator sitting in Tripoli.

As ever, I digress. My point is simply that it is quite the trajectory the Gaddafis ended up being on. One day they were lauded in London, and grandees couldn’t move for invites to meet them. The next moment they were waving their digits and promising to fight to the last bullet, never expecting the last bullets would be aimed at themselves.

I suppose most countries, like most sensible people, would like to find the still point in this spinning world. The best way to achieve that would be to find someone – paid or unpaid by the fairground – who has the nerves, skill and staying power to show us how to get there.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.