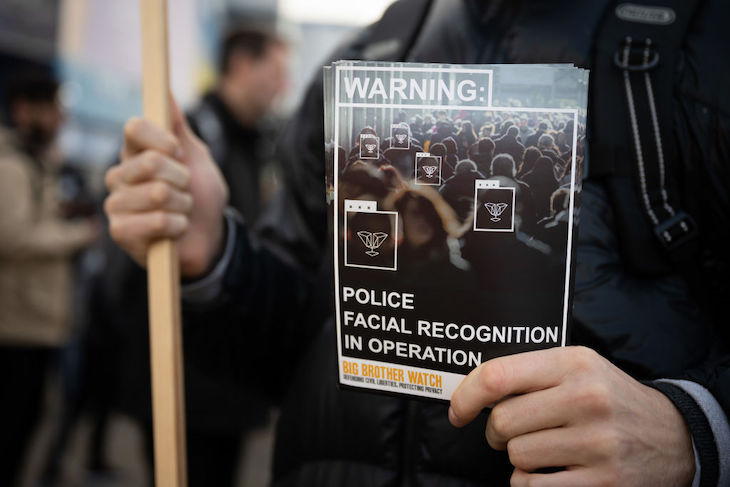

Shabana Mahmood’s announcement that facial recognition is to be rolled out across the nation is no vague statement of aspiration. Part of wider policing reforms and backed by the promise of fifty more camera-topped vans, the Home Secretary’s announcement signals the government’s determination to make mass surveillance part of daily life. Combined with the current consultation on facial recognition, it also confirms that Britain is becoming a surveillance state without any real thought or debate.

Mass surveillance isn’t compatible with a healthy society

The focus of the public consultation on a new legal framework for the use of biometric surveillance technologies by law enforcement agencies is framed in ‘when did you start beating your wife?’ terms. It assumes that the people of a liberal democracy have already consented to a national surveillance system which will profoundly change the relationship between state and citizen.

Over the past decade, police have increasingly used live facial recognition to identify possible criminals. Since cameras surveilled the crowd at the Notting Hill Carnival in 2016, facial recognition vans have been appearing in various parts of London and other cities, with the first permanent cameras installed in Croydon. Over the past year in England and Wales, police have scanned the faces of over seven million passers-by.

All this has happened amid rumblings of concern and in something of a regulatory vacuum. In a slight of hand which glosses over the lack of democratic process, the Home Office presents the consultation as the beginnings of a remedy. More candidly, it admits that the purpose of a new legal framework for facial recognition is to ‘give the police sufficient confidence to use it at significantly greater scale’.

Accordingly, the consultation kicks off with a series of questions about which technologies the framework should permit, avoiding any first-principle enquiry about whether live facial recognition should be used at all. In contrast to continental Europe where the EU AI Act restricts the use of live facial recognition for law enforcement, the Home Office assumes the introduction of cameras to every town and city is simply a matter of adopting ‘a valuable tool to modern policing’.

This technocratic attitude reflects a wider shift in Britain’s political establishment in which democratic principles are set aside for the excitement of what ‘works’. We would do better to pause and consider what new world we are ushering in. Mass surveillance upends the presumption of innocence that has traditionally characterised the British justice system. It violates the right to privacy which underpins our cherished anonymity in public space and the requirement that explicit consent be given for the use of biometric data. And it imperils a way of life in which people go about their business without undue interference from the state.

Having jettisoned the ‘what’, the consultation deals only with the ‘how’, suggesting that the bother of ‘Parliament considering each new technology’ could be saved if the public would give advance consent for the use of emerging technologies. One question asks whether police should use inferential technology to predict criminal action from body language, another whether object-recognition technology should flag up wanted individuals by their hats and coats. A question about ‘other technology types’ could take in any number of unspecified future developments. All this goes well beyond matching a face to one on a watchlist and would give the police carte blanche to use experimental surveillance techniques on the British public.

The potential for both abuse and mistakes is enormous. As the case of Shaun Thompson, who is taking the police to court after being wrongly identified as a suspect while being filmed at London Bridge station, illustrates, facial recognition technology is error-prone. Facial expressions are not a reliable indicator of human emotion, nor can body language be understood as a universal predictor of action. And yet the College of Policing and Home Office seem to be rubbing their hands at the prospect of unleashing AI on the public in a new age of ‘predictive policing’.

The suspicion that government would like all public space, indoor and outdoor, under continuous surveillance is supported by a telling admission by the Home Secretary

The state’s appetite for surveillance isn’t confined to policing, and didn’t begin with the current government. In March 2023, policing minister Chris Philp and Home Office officials held a meeting with Facewatch, a company supplying facial recognition technology to the retail sector. Officials subsequently agreed to write to the Information Commissioner’s Office to persuade the body charged with protecting our privacy of the benefits of using facial recognition to tackle shoplifting. This month, Sainsbury’s announced plans to use facial recognition technology in its stores.

The suspicion that government would like all public space, indoor and outdoor, under continuous surveillance is supported by a telling admission by the Home Secretary. ‘When I was in justice, my ultimate vision for that part of the criminal justice system was to achieve, by means of AI and technology, what Jeremy Bentham tried to do with his Panopticon,’ Mahmood told Tony Blair at his think tank’s Christmas do. ‘That is that the eyes of the state can be on you at all times.’

Bentham’s panopticon – a circular prison in which inmates live in fear of constant surveillance from a central watchtower – was used by the French philosopher Michel Foucault to highlight a dangerous aspect of modern society. Foucault argues that centralised scrutiny extends beyond the prison system to other areas of public life, creating a self-censoring, docile population. Mahmood’s blithe endorsement of the model illustrates how Britain’s leaders are forgetting the hard-won lessons of modern history, truths we didn’t have to learn the hard way. The technology of biometric surveillance may be new, but mass surveillance is not. Apart from the ones we’re still watching – China, North Korea – societies which imposed mass surveillance have generally ended in revolution or collapse. I’ve stood in museums in Berlin, Lisbon and Tirana peering into glass cases where the paraphernalia of surveillance is presented as evidence of human folly gone by.

As I wrote in The Spectator last year, mass surveillance isn’t compatible with a healthy society. Long after the collapse of the dictatorship in Albania, the effects of corrosive surveillance live on. I only hope that we, in the cradle of liberal democracy, remember that we know better.