Agatha Christie, who died fifty years ago today on 12 January 1976, possessed a genius for making the ordinary strange. In her imagination, the sleepiest lanes of the English countryside could, at any moment, become the setting for murder. Yet alongside the vicars, the colonels and the gossipy spinsters, another set of figures appears again and again: the excitable foreign maid, the prim continental governess, the French girl with a secret, the nervous Polish refugee working in the kitchen.

Alongside the vicars and gossipy spinsters, another set of figures appears again and again: the excitable foreign maid, the French girl with a secret

Foremost among them is, of course, the Polish housekeeper Mitzi in A Murder is Announced (1950). Christie presents her by turns as comic relief and plausible suspect. She is forever screaming, convinced that her employers intend to poison her and that Nazi spies remain on her trail, even in the tranquil village of Chipping Cleghorn. ‘They laugh at me, they call me crazy,’ she cries, yet insists that she notices things others overlook. To the English she seems absurd, but her hysteria has its roots in real trauma.

By the late 1940s, tens of thousands of Poles had found their way into British society: soldiers who fought alongside the Allies, civilians unable to return to a communist-run Poland, and displaced refugees. The Polish Resettlement Act of 1947 introduced some 200,000 Poles into British life. Many secured jobs in industry; others worked in kitchens and sculleries. Middle-class households that once employed local cleaning women suddenly found themselves with staff who had thick accents and vivid wartime memories. Mitzi, however, was more than a comic invention. She was an acknowledgement of a new social reality.

Christie heightens every trait until Mitzi becomes melodrama personified, the archetype of ‘foreign hysteria’ set against Miss Marple’s unflappable logic. Yet Mitzi plays a crucial narrative role. Her muddled, exasperating testimony is also the clue that helps Marple discern the truth. She obstructs and enables in equal measure. She is both indispensable and suspect – much like many migrants living in Britain today.

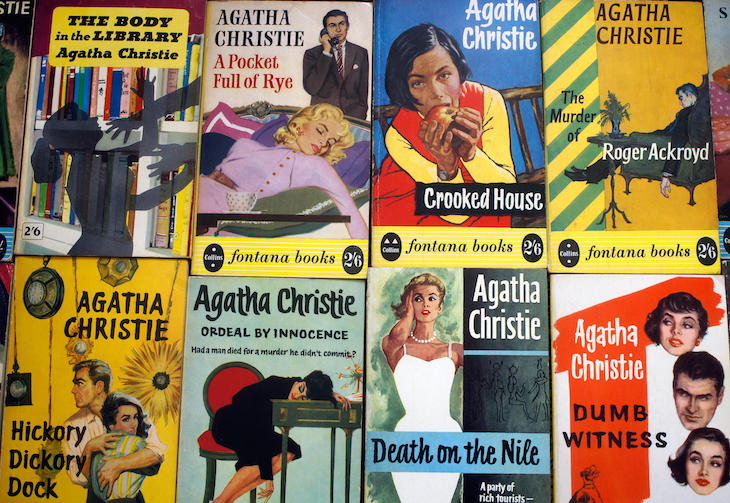

Nor was this Christie’s first use of such a device. The French maid Louise Bourget in Death on the Nile (1937) is sufficiently vain – and sufficiently desperate – to attempt blackmail. The German governess Fräulein Schmidt in Cat Among the Pigeons (1959) brings discipline and rigour to Meadowbank, only to be drawn into conspiracy. Mlle Brun, the French governess in The Secret of Chimneys (1925), hides revolutionary zeal beneath impeccable manners and a delicate accent. Greta Ohlsson, the Swedish missionary and former nurse in Murder on the Orient Express (1934), blushes and stammers her way through interrogation while timidity masks guilt. Each is simultaneously insider and outsider: intimately acquainted with the household, yet never quite belonging to the place. Their accents and mannerisms set them apart, and Christie extracts narrative gold from that difference. They become living, breathing red herrings.

To the modern reader, the stereotypes may seem broad. Yet they also reflect the social realities of Christie’s world. Her contemporary readers recognised the types because they encountered them daily: the governess who brought Swiss or German order to the nursery, the housemaid whose French was more polished than her English, the Polish refugee whose presence felt incongruous in the corner shop. The stereotype worked because the original was so familiar.

This, I think, is why Christie’s fiction still carries a certain relevance. Mitzi is unmistakably a caricature, yet she also embodies a truth: that much of the essential work of this country has long been done by outsiders. In the 1950s, it was Poles in the kitchens and laundries. Today, it is Romanians on building sites, Nigerians in hospitals, Filipinos in care homes. These workers are rarely the targets of public anger; their value is broadly acknowledged. The sharp edge of political debate now turns instead on the so-called illegals, the small boats, the benefit-seeking migrant.

The tittle-tattle of St Mary Mead treated all foreigners with equal suspicion; contemporary Britain, however, distinguishes between them. The Polish carer and the Romanian fruit picker are considered essential. Controversy centres on those outside the labour system. Yet the underlying paradox remains. Mitzi’s neighbours tolerated her tantrums because someone needed to cook the dinner. Britain, for all its protestations, still cannot function without its migrant workforce, legal or otherwise.

Christie’s foreign characters may seem today merely obvious types, almost the stage props they resemble, but they reveal something subtler about the country. The ‘finest quintessentially English tales’ were not, in truth, entirely English. They relied on outsiders – for texture, for labour, and quite literally for the machinery of the plot.

Which brings us to the final twist. For in Christie’s England, the foreign servant was seldom the true villain. The real suspect, of course, was always Britain itself.