The fundamental purpose of science is to view the world from a different perspective. In the age of modern science, however, in which each academic discipline represents a world in itself, this is hard to remember. The field of ‘tribology’ would appear to be a perfect example. But such opacity is merely a front for the study of friction. And, according to Jennifer R. Vail, friction is ‘the unsung hero of the material world’. Why? Because ‘the way we experience the world, whether through greater efficiency, flight or space exploration, has been shaped by our understanding of friction’.

Indeed, ‘our relationship with friction dates back to one of humanity’s greatest discoveries: fire’. How’s that? Well, as Vail explains, the mastery of fire is really the mastery of friction, right? Look again. Fuel and oxygen are abundant. But heat? ‘The act of rubbing objects together produces friction,’ and therefore heat. Simple. But Vail’s book is more than just a lesson in perspective. It is a study of scientific progress.

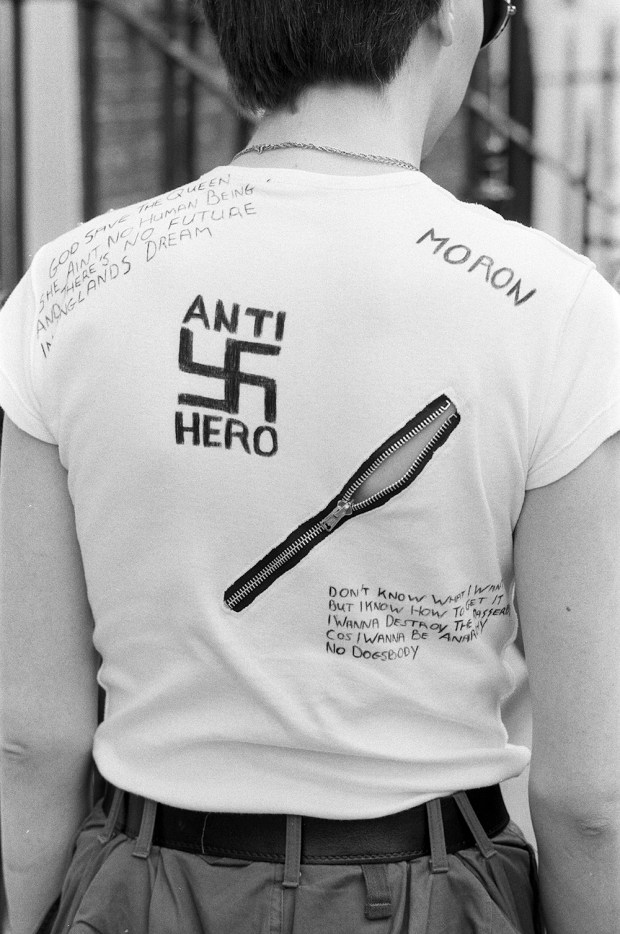

Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific studies of friction were centuries ahead of their time

In the 20th century, the automation of heavy industry led to productivity on a previously unimaginable scale. The downside of such monumental efficiency was that even the tiniest flaw ‘cascaded through the production line’. Across the United Kingdom in the 1960s, ‘extreme production delays’ were being caused by malfunctioning equipment at iron and steel plants attributed to inadequate lubrication.

The solution was not simple – nor was it a local difficulty. Industry representatives and engineers examined equipment failures throughout Britain, the United States and Germany only to find that the problem was the machines themselves. ‘The old designs weren’t equipped to handle the wear and tear of continuous operation.’ New designs were required; and if progress was to continue, this meant that a ‘new discipline of science’ was needed, involving ‘the marriage of chemistry, physics and engineering to see how surfaces interact’. In this way, tribology was born, and once again it was time to re-examine the world.

Of course, the study of friction is nothing new; and to explain the 20th-century crisis, and to understand where tribology may yet take us, we must first understand how we got here. So begins Vail’s brief but enjoyable history of human progress, seen through the lens of rubbing and lubrication.

Once the pyromaniacs arrived, ‘the ability to manipulate friction fuelled many of humanity’s most significant cultural achievements’. Take the Egyptians, who – as physicists showed in 2014 – manipulated frictional forces to pull 60-ton objects across the desert sands; or the wheel, the ‘tribological trick’ of the Romans, which needed friction to move and was itself overcome by frictional heat unless lubricated. (Horace describes how chariot wheels would glow during racing.)

History swiftly progressed from the ingenuity of the ancients to the extraordinary genius of Leonardo da Vinci, whose unpublished writings were the first scientific study of friction and were centuries ahead of their time. But by the middle of Vail’s second chapter, the energy of the writing diminishes and it becomes clear that the book is intended more as a textbook. Especially because, as Vail notes, ‘friction is ignored in high school physics classes’, and therefore she must explain everything. So, for example, we learn: ‘The Roman Emperor Caligula [was] a brutal dictator who enjoyed ambitious construction projects…’

Gradually the structure gets murkier, and you begin to sense that Vail is telling you everything she knows in no particular order (and you still don’t really see how tribologists solved the industrial crisis). Nevertheless, some of the applications of tribology are truly wonderful, no matter how they’re delivered. We learn that creatures such as the green anole use friction to walk on walls and that the discovery of a ‘solid lubricant’ is compelling evidence that life began on Mars. Unfortunately, when Vail slips back into the theoretical underpinning and we read sentences such as ‘…and like graphite, molybdenum disulfide gets its lubricous nature from its similar hexagonal chemical structure…’ the music stops.

Still, if you make it through energy audits, Crayola, electric vehicles, weather dynamics, plate tectonics, fluid mechanics and the science of coatings, you will realise that friction really is the unsung hero of the material world – and you can tell people smugly that the mastery of fire is really the mastery of friction.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.