Donald Trump’s rendition of Nicolas Maduro was a brilliantly executed coup. It was also an exhibition of America’s hard power, power that has underpinned the rules-based international order that protected America’s allies for decades. Now those allies fear that the rules-based order is as much a smoking ruin as Maduro’s Caracas compound. European hysteria is, however, misplaced. President Trump has not inaugurated a new era of disorder, he has responded to realities about which European elites have been in denial.

The post-war international order has been crumbling for more than a decade. And British governments have been enablers of that process. One of the most determined users of hard power in subverting every restraint has been communist China. British policy, accelerated under this government, has supported China’s economic rise and acquiesced in its suppression of freedoms.

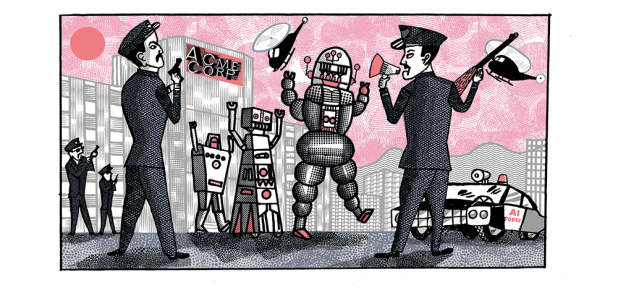

The rules-based international order only works if its adversaries are too scared to defy it

We were cheerleaders for China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation, assuming that would tame Beijing’s authoritarianism. Instead, China turned our naive belief in free trade and our faith in trans-national institutions into a mechanism for transferring jobs, intellectual property and wealth into their hands.

Our drive towards net zero and attachment to the Kyoto Protocol have allowed us to become dependent on Chinese technology manufactured by slave labour in Xinjiang. And we have proved false friends to those actually invested in democratising China. Britain had promised Hong Kongers autonomy through the Basic Law. Instead Beijing was able to subvert the city, eventually subsuming it into the mainland.

Whether it was misplaced post-colonial guilt, or wilful naivete, the same instincts are also in play in our surrender of the Chagos islands to China’s ally Mauritius. We think we are adhering to the international law rule book. China sees a shrivelled, cuckolded nation trying to hide its impotence behind the fig leaf of Richard Hermer’s legal opinion.

Prior to Trump’s return to the White House, Joe Biden’s America displayed similar evidence of exhaustion. The fall of Kabul and the collapse of American might in the face of teenagers with Kalashnikovs was no triumph of rules-based order. Rather, it was a demonstration of hypocrisy and infirmity. The Taliban was able to overrun 20 years of US occupation in just a few weeks.

For those who argue that Europe offers a brighter alternative to either British or American statecraft, consider the failure of the 2015 Minsk II Agreement in guaranteeing Ukrainian sovereignty. A defence pact orchestrated by France and Germany collapsed in the face of Vladimir Putin’s war machine. Russia has contempt for a continent that spends massively on welfare while flinching from preparation for warfare.

Any notion of an international order works on two conditions. The first is that those who are a part of it choose to enforce it; yet the West has repeatedly failed to uphold its promises. The second is that the adversaries of international order are too scared to defy it. Maduro made clear that he was not scared. He traded oil for loans with China while helping Moscow avoid sanctions. He rigged elections and had opposition activists shot in the street. He allowed fentanyl and weapons to flood across America’s southern border. Trump put an end to that.

Maduro was part of a web of dictators. Thirty-two Cubans were killed in the raid on his compound; they were part of a communist bodyguard corps from another dictatorial regime. Venezuelan oil props up Havana. Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, believes that toppling the dictator of Caracas could hasten the end of Cuban misery. Those on the streets of Havana will be watching, hoping for liberation from poverty and dictatorship, rather than worrying that international law has been breached.

The people who have genuine cause for concern, however, are our enemies. Caracas’s air defence systems were mostly Russian-made. They were unable to down a single aircraft or even kill a single American serviceman. Russia now knows the superiority of American weapons systems. That sends a message, one that differs from the fiasco in Kabul that emboldened Putin in his invasion of Ukraine. It also sends a message to Russia’s customers, such as the Belarusians, who use the same Buk-M2 anti-aircraft missile systems as the Venezuelans, and the Iranians, who use the Pantsir-S1s that also failed. Russian defence systems can be overawed.

European leaders saw the supremacy of American technology too. The offer is there from Trump: choose to invest in your militaries, to defend your own homelands, and we’ll sell you the arms. America can grow its domestic defence industries and Europe can fend off its enemies. Trump’s administration has repeatedly expressed its desire to enact this win-win. The White House’s national security strategy, published last month, was explicit: ‘We want to support our allies in preserving the freedom and security of Europe, while restoring Europe’s civilisational self-confidence and western identity.’ This belief in basic western values was evident when, this time last year, J.D. Vance chided European leaders for failing to uphold western freedoms.

Instead of laying claim to a virtue they have scarcely exhibited themselves, British and European politicians should heed the wise words of Peter Mandelson. In his Ditchley lecture last year, and again in our pages, Lord Mandelson displays a clear-eyed assessment of how to work with Trump which is much more acute and constructive than his detractors have offered. If we want to exercise influence, win respect and secure our interests, then we need to invest in our hard power. International law is a palisade of paper; it is by following the iron laws of hard statecraft that we serve our people best.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.