Gerald Murnane’s Landscape with Landscape opens with a splendidly disgruntled preface. The book is a collection of six longish stories and was originally published in 1985, when it was panned by a reviewer. ‘Some writers may claim not to be affected by reviews or even not to read them,’ he observes in his preface: ‘I make no such claim.’ And he explains how this brutal notice (‘I call to mind easily some of the nastiest passages’) led to poor sales and the disappearance of the collection, his fourth book.

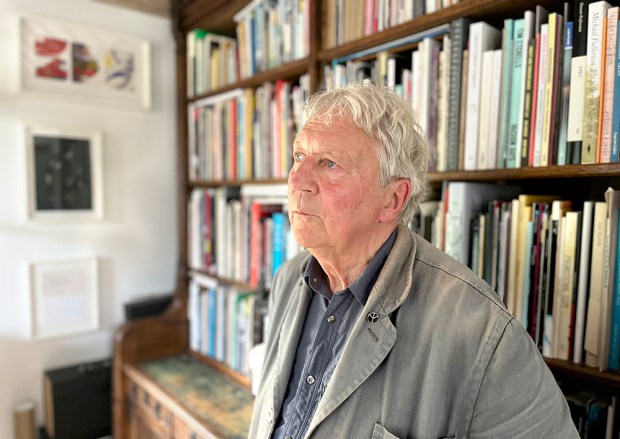

There is some comedy in this alongside the spiky pathos. Murnane is about as close to review-proof as any writer can get. Now 86, he is often mentioned as a likely contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He has high-minded admirers (J.M. Coetzee, Ben Lerner); and the fact that his books are considered worth reissuing 40 years on is a sign of his cult status. But they are Marmite (or perhaps Vegemite, given that he is Australian). You either love his stuff or roll your eyes at it.

So: what is his stuff? Murnane writes in a curious and faintly otherworldly rhythm. His sentences are often flat and his paragraphs recursive, yet build up to moments of evocative and surprisingly lyrical insight and beauty. The first story in this collection, ‘Landscape with Freckled Woman’, describes an encounter between a character much like Murnane with a woman at a committee meeting. Over a plate of biscuits and tea she asks him fairly banal questions, and these set off a chain of memory, as the old man remembers the idealistic young man he had once been, who longed to be a writer.

This is all very high modernist: epiphanies in the everyday, a figure who is also the author, and the rejection of much of the conventional baggage of fiction: character, plot, development. ‘At about this time he married,’ writes Murnane of his protagonist, and that is all the detail he gives.

Yet Murnane’s writing – this collection and his novels, the most celebrated of which is The Plains – also turns upon one of the great questions of Romantic literature. How do we grow into ourselves, and, as we do, what is our relationship with the world around us? The second story, ‘Sipping the Essence,’ begins with a group of young men in a grotty rented flat in Melbourne. They live off porridge and sardines; they are ‘unqualified with girls’; it is New Year’s Eve of 1959, the night before the 1960s.

But this being Murnane, the story then swerves from promisingly slapstick set-up and describes a rivalrous friendship between one of the young men, named Kelvin Durkin, and the narrator. The narrator is another stand-in for Murnane: he talks about Jack Kerouac and dreams of becoming a writer and escaping into the wilds of Australia. Durkin, by contrast, borrows his extremely efficient pick-up lines from magazines and does not suffer from daydreams. The story then plays out variations on this conflict between conformity and art, between the suburbs and the imagined north, over the following years.

The stories are linked as in a daisy chain: the title of the second is mentioned in the first, and in the second the young man plans to write a story with the title of the third. This story, ‘The Battle of Acosta Nu,’ is the most disturbing and moving of the collection. A second-generation Australian expat in Paraguay watches over his son dying of septicaemia in a hospital, but can only think obsessively about his homeland that he has never been to. Like all the characters in these stories, he is dreaming of Australia, and made powerful and yet weakened by those dreams.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.