‘On BBC 2 last Monday,’ noted the Sunday Telegraph’s TV critic Trevor Grove in February 1979, ‘the return of Fawlty Towers was immediately followed by a programme about faulty towers.’ He went on:

This was odd, but on close examination turned out to be without significance. After all, what connection could there possibly be between a comedy series based on the exploits of a domineering, havoc-wreaking megalomaniac called Basil Fawlty and a serious study of what has been done to Britain’s urban environment by a bunch of domineering, havoc-wreaking megalomaniacs who call themselves architects?

The programme was Christopher Booker’s still remembered City of Towers, a ferocious attack on Le Corbusier-inspired concrete high-rise, especially when used for public housing. Five years later, another notable TV documentary, Adam Curtis’s The Great British Housing Disaster, a coruscating, detailed examination of the system building of the 1960s, involving pre-cast slabs and dangerously easy on-site assembly, was a further nail in the coffin for the reputation of postwar high-rise social housing.

Politicians weighed in, too. ‘Slums that defy description’ was Michael Heseltine’s 1987 verdict on Liverpool’s tower blocks. Margaret Thatcher, much influenced by Alice Coleman’s Utopia on Trial (1985), would lament how ‘the vast, soulless high-rise council estates’ had become ‘ghettos of deprivation, poor education and unemployment’, places whose tenants ‘mutually reinforce each other’s passivity and undermine each other’s initiative’ – in short, encapsulating the very worst vices of the welfare state.

Writing about postwar Britain, I have found it hard not to be influenced by this and much similar rhetoric, coming mainly, though not solely, from the right. It has also been difficult not to be shocked by the arrogant disregard of all the surveys over the years conclusively showing that most people wanted to live not in a flat, whether high-rise or otherwise, but in a house with its own garden, however small. To take one example among many: in 1962, just as slum clearance and the building of high-rise council estates was about to hit peak intensity, a survey of Leeds slum-dwellers revealed that among the young and middle-aged only 5 per cent wanting to move into a flat. Popular tastes, to the despair of a modernist architect such as Rodney Gordon, remained stubbornly old-fashioned. He wrote in disgust at about this time, after his pilgrimage to the new, high-profile, high-rise, Corb-inspired, hard-modernist estate at Roehampton:

The windows were covered with dainty net curtains, the walls were covered with pink cut-glass mirrors and ‘kitsch’ and the furniture comprised ugly three-piece suites, not even the clean forms of wartime utility furniture.

Holly Smith, in her impressive, highly knowledgeable and crisply written survey – essentially a series of case studies about high-rise social housing – does not shy away from serious failings, whether in relation to the buildings themselves (too often poorly built and always expensive to maintain) or the way the local authorities ran them (too often unsympathetic and overly bureaucratic). She shows how the selection of who went to live in Sheffield’s showpiece ‘streets-in-the-sky’ Park Hill development was in effect a policy of social engineering, based on the Victorian distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. She is unsparing about the justly notorious ‘Piggeries’ of Everton; and her account of the aftermath of the Ronan Point disaster of May 1968, involving attempts at an utterly discreditable cover-up, is truly eye-opening.

Even so, at the heart of Smith’s book is the case, if not exactly for the defence, then certainly for a much more nuanced treatment of the whole phenomenon:

High-rise housing is routinely castigated as monotonous. If we take the time to look up – to actually look – we find otherwise. These blocks make up a fantastically varied part of Britain’s built heritage. Modernism is marked in its multiplicity. This was no narrow architectural tract; it evolved, expanded and pluralised across the course of the 20th century.

And again:

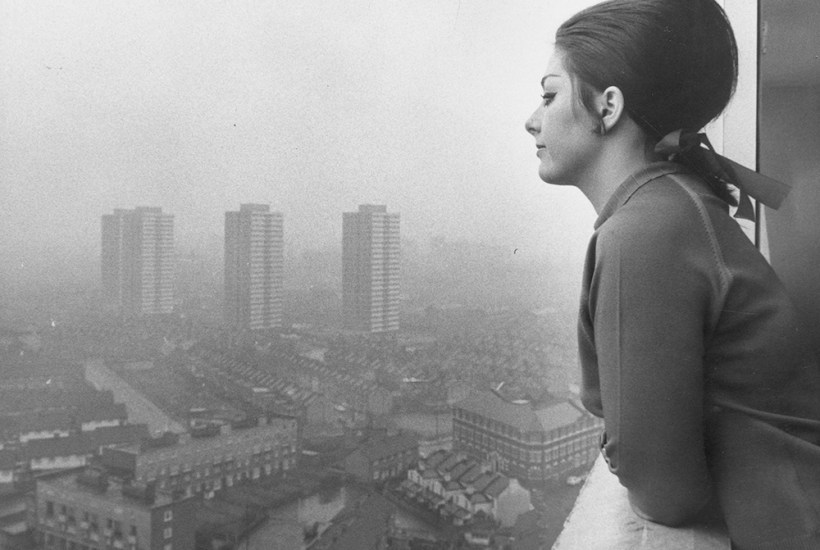

Many tower blocks had solid structures. Some were architecturally superb. Lots were average but humane, providing commodious dwellings with novel mod cons and lovely views.

Whatever one’s personal prejudices, these are surely valuable correctives. Moreover, arguing that architectural modernism was not just about functionalism, Smith even seeks to redeem the great man himself. In Vers une architecture (1923), Le Courbusier declared:

Architecture goes beyond utilitarian needs. You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces. That is construction. Ingenuity is at work. But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good. I am happy and I say: ‘This is beautiful.’ That is architecture. Art enters in.

Crucial to Smith’s broad thrust is that the attitudes and feelings of high-rise flat-dwellers were far from uniformly negative once they were actually in their new homes. A 1967 survey of Park Hill tenants found only low levels of dissatisfaction. ‘It was a nurturing environment in which we could start a family, surrounded by people we could trust,’ remembers Sorys Angel about the St Katharine’s Estate, Wapping, of the 1980s; and the Liverpool writer Jeff Young has described the experience of researching a play based on the testimony of that city’s high-rise tenants:

Time and again, people told us how much they loved living in these buildings. A woman called Josie Crawford talked to me of beauty. When she woke in the morning she could hear the sound of the milkman all those floors below, and in the evening she told me she could see the river and it shone like sweet wrappers.

Sometimes, as Smith shows in illuminating detail, this affection took the form of organised resistance by tenants – a resistance as equally likely to be against attempts by central government to take over or privatise their estates as it was to be against the inefficiencies of local housing departments. A particularly resonant case study is that of the Ocean Estate in Stepney. Its very active Tenants Association was fiercely opposed in the late 1980s to the Thatcher government’s Housing Action Trusts (HATs) scheme that sought to transfer ownership away from Labour-controlled councils.

Smith’s own sympathies are clearly with this resistance. But she also brings out that the well-established Ocean tenants, almost invariably white, were quite capable of dishing out racist abuse – and occasionally worse – to Bangladeshi newcomers on the estate. ‘Whose fault is it that our flats are falling down on our heads?’ asked in vain a member of the Tenants Association at a ‘tempestuous’ anti-racist workshop in Stepney in 1984. ‘We shouldn’t get diverted. The real issue is bad housing.’

Smith’s achievement is considerable, and it is wonderful to have an architectural historian writing about people as much as buildings. Yet, as we look back on one of the major ‘New Jerusalem’ experiments, much of whose physical legacy has been ruthlessly demolished, I find myself still instinctively sympathising with the town planner Frederic Osborn. Writing in 1945 to the great American urban prophet Lewis Mumford, he called the growing momentum behind the concept of ‘large-scale multi-storey buildings in the down-town districts’ not only ‘a pernicious belief from the human point of view’, but also ‘a delusion’. Or put another way: yes, human beings are adaptable, almost infinitely so; yet at that crossroads moment, the path taken went against rather than with the grain of tradition-valuing, privacy-valuing, garden-valuing human nature.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.