The US government in recent years imposed global rules that prevent any company anywhere from selling advanced computer chips or the equipment that makes them to China. Washington thought Beijing could never outflank this restriction.

No one thinks that any more after Beijing announced global rules that weaponise its production of rare earth metals and magnets. The edict said that any company anywhere wanting to sell anyone any product that has even a tiny amount of these essential tech ingredients sourced from China would need a licence from Beijing.

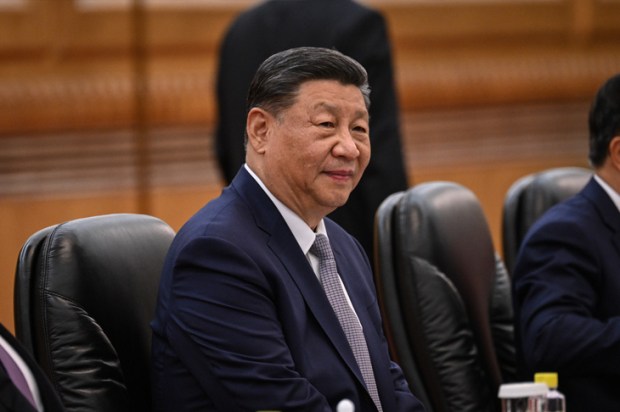

This display of China’s geoeconomic might came as the Communist party of China held a plenum to discuss the country’s 15th five-year development plan, for 2026 to 2030.

Past plans amassed resources for technological and green ‘industries of the future’ and strategic dominance in rare earths and pharmaceutical ingredients. That’s why China can seemingly hold the world hostage economically.

But wait. Beijing delayed imposing restraints on rare earths in exchange for lower US tariffs.

Why? Beijing back-pedalled to ward off more retaliatory blows against China’s spluttering manufacturing-based, export-led economic model that, by flooding the world with goods, irritates trading partners.

China’s problem is it’s stuck with its flailing economic model because its policymakers can’t upgrade to an advanced-world prototype where household consumption drives the economy.

This inability is undermining China’s relative economic power. The size of China’s economy relative to the US’s has declined from a peak of 77 per cent in 2021 to 64 per cent now using IMF data and market exchange rates. China’s problem is it can’t overcome how its one-party political system acts against economic advancement.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s book of 2013, Why Nations Fail, explains China’s insurmountable handicap. The authors sought to understand why only some countries get rich. They found the incentives promoted by a country’s institutions lead either to poverty or prosperity, and that politics determines what institutions a country possesses.

In short, rich countries have pluralistic political institutions that form and sustain inclusive economic institutions. The diffused sources of power in these countries combined with the rule of law, secure property rights and a market economy foster the ‘creative destruction’ articulated by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter that leads to prosperity.

Countries that stay poor are those with ‘extractive’ institutions that concentrate power and opportunity to a few. Acemoglu and Robison wrote that ‘fear of creative destruction is often at the root of the opposition to inclusive economic and political institutions’.

A communist dictatorship is a classic extractive political institution that stymies creative destruction. The country’s reliance on extractive institutions manifests in (at least) five pitfalls that, combined with the curse of excessive debt and a shrinking population that China shares with advanced countries, arrest its economic advancement.

One is the lack of household consumption. China’s consumption is just below 40 per cent of GDP compared with at least 60 per cent in rich countries and the percentage will struggle to rise. (Some bodies give a higher reading for China’s consumption. But all say the country lags advanced ones.)

The problem is Chinese households feel too insecure to spend. People save as the country lacks a modern welfare system. State resources instead subsidise industry while an artificially low exchange rate and suppressed interest rates favour industry over consumers. The property crisis that began in 2021 has impoverished families and boosted unemployment, thereby inhibiting spending.

Another extractive-related handicap is distorted incentives motivate business to overproduce.

In capitalist countries, the price mechanism limits production to profitable goods. But this efficient way to allocate resources is broken in China for two reasons. The main one is party officials get promoted for delivering growth at any cost in their remits. The other is the value-added tax on goods, China’s main revenue-raiser, is shared between Beijing and the local government where goods are made, not consumed. Overcapacity is a bigger problem of late because local governments rely more on VAT now the property crisis limits their ability to raise revenue from selling land.

This excess production causes deflation, squeezes profits, thus employment and reinvestment opportunities, deepens trade wars and limits innovation.

A third extractive-related impediment is restricted competition (or brake on creative destruction) that leads to low productivity and the misallocation of resources. While Beijing permits private companies, they are not allowed to challenge state-owned companies that are sources of riches and employment for party members. Nor can they disrupt private companies favoured under industry policy. Restricted credit is one way that’s done. Companies that become giants in new industries are hobbled too – note how Beijing disappeared Alibaba’s high-profile CEO Jack Ma in 2020.

A fourth handicap is the uncertainty surrounding succession, a perennial problem for autocracies made worse by President Xi Jinping, who on gaining power in 2012 ended the post-Mao process for handling successions. The 72-year-old did this by abolishing presidential term limits, using an anti-corruption drive to purge rivals and by not anointing a successor who would then be vice president. These steps could lead to political havoc and thus create uncertainty that deters household spending and business investment.

The fifth impediment is immature capital markets. The absence of the rule of law, secure property rights, an independent central bank and trusted economic data and government meddling with price settings and capital flows prevent China from developing the deep and sophisticated capital markets that funnel savings to investment opportunities in advanced countries.

Given these challenges, China’s autocrats always double down on plans to ensure China remains a manufacturing and export powerhouse, as the plenum just did, which will only hasten the country’s relative decline. For all China’s technological and industrial flexing and geoeconomic smarts, China’s economy’s development is snookered unless the political system changes. And there’s no sign of that.

Other ways exist to assess Peak China besides using GDP as a proxy for global economic power. But output is pertinent enough especially when its drop is abrupt. For sure, China industrialised under extractive institutions from 1978 when its economy was nine per cent of the US’s. But that was due to landmark reforms that were one-offs. No question that Peak China economically doesn’t equate to Peak China militarily. No argument either that Beijing is talented at maximising its weakening economic strength.

But even the smartest mandarins can’t overcome the handicap that an extractive one-party state imposes on economic advancement. Not even if China holds sway over rare earths.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.