Back in Australia after six months in England and America. London packed with tourists but overall is more depressing than on my previous visit. In the Bloomsbury/Covent Garden area where I’m staying there are a lot of people living on the streets – many with tents, some double-occupancy and with a dog.

The large soup kitchen next to Goodge Street Station serves three courses and has numerous customers, many of them well dressed and appear middle-class; not down and out.

Old friends, many of them very old friends, from my years in London from 1963 to 1972, are unanimous that the British withdrawal from the European Union was calamitous. Not only have the euro-subsidies stopped but jobs in Europe are once again subject to passport checks, visas and a laborious online application process.

London is expensive, even more expensive than Australia. Cinema tickets are frequently $40 or more, beyond the reach of many younger film-goers. A further factor in the diminishing attendances worldwide are the large home TV screens and superior sound systems. A number of friends back in Sydney have told me, irritatingly, that they never go out to cinemas anymore. My protests that the largest TV screens and speakers just can’t match a cinema screen with surround sound are casually ignored. My suggestion that watching films with a responsive audience is more enjoyable than a home viewing with a couple of people is similarly dismissed.

Some of the largest London movie theatres have closed. Luckily there is a small but modern arthouse in Bloomsbury, where for around $50 I saw a superb new copy of Stanley Kubrick’s three-hour masterpiece (his only one, in my opinion) Barry Lyndon, a meticulous and exciting adaptation (Kubrick is credited with the script) of a great novel.

Cinemas may be having a bleak period but London theatres are booming. Perhaps it’s just the summer tourist season but the majority of live productions are musicals, not plays. Finding any seats at all is a trial even for the most resourceful. The Abba Voyage concerts, performed by four holograms of the once-again youthful singers, are permanently packed with many tickets costing around $400.

I thought the musical version of The Great Gatsby was visually inventive but found the songs pedestrian. A revival of Lionel Bart’s musical of Oliver was also staged with flair and was such a delight I’d probably have happily paid double.

A quick trip to USA. My son is an academic in Boston. An ancient philosopher. I’m still struggling with French after years of study, while he casually reads books in Greek and Latin. (I can now read French with some fluency but invariably fail to understand even a simple greeting from a French speaker). Visited the Boston Museum with its superb pre-Columbian collection, plus masterpieces by Winslow Homer, Sargent and Whistler.

A few days in New York. Called on Alfred Uhry, who wrote the play and film script of Driving Miss Daisy, which I directed to an Academy Award for Best Film in 1990. Alfred is now over 90 but is as acute as ever. He is still writing and has seen, it seems, every play running in New York. He didn’t share in the widespread acclaim for the Australian production (now running in New York) of Dorian Gray. He quietly questioned the point of presenting the play with one actor doing all 26 roles (why?) and found the numerous cameras and screens with assorted images irritating, claiming they distracted from the drama rather than enhanced it.

A visit to Carnegie Hall for a stunning performance of Dvorak’s New World symphony, which had its premiere there in 1893. The New World had a tremendous and almost instantaneous effect on the course of American music as Dvorak stressed the importance of the melodies and structure of American jazz and Indian music, rather than classical works from central Europe.

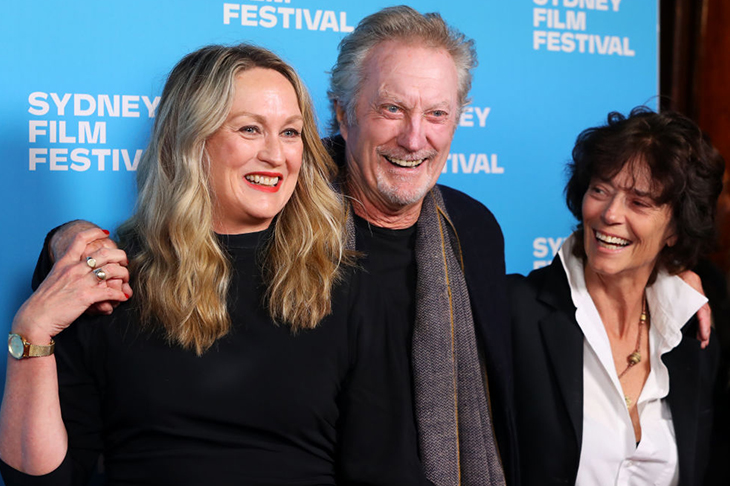

My return to Australia is timed so that I can join in the promotion schedule for my new film, The Travellers. Sony, the distributors, send me off to various cities, large towns and even small towns (I’m currently the toast of Boolaroo) around Australia in the struggle to lure people away from their TV sets and online entertainment. I introduce the film over and over and am often interviewed at the conclusion of a screening, aware that many (most?) audience members have only a vague idea of what the director on a film actually does.

Bryan Brown has a leading role in The Travellers. I last worked with him on Breaker Morant around 1980. A gifted actor and amiable personality, he headed a talented cast and was clearly adored by the excellent WA film crew. No slouch, he’s written three successful novels in his spare time.

Filming went smoothly despite a month of rain and it was only the insane regulations that produced moments of irritation and tension. The director is now no longer allowed to speak to the extras in crowd scenes but has to convey his direction through an assistant.

In London, a few years ago, it was pointed out to me on a film set that not only would the budget go haywire if I spoke to the extras; it was essential they didn’t move during a scene as this involved further payment. Not surprisingly, I found that a mute and motionless crowd didn’t do much to bring the scenes to life. Who invented these bizarre rules and who agreed to observe them?

A further problem contributing to the escalating cost of films is copyright. Virtually every sign, every poster, every work of art seen in a film has to be cleared in writing by the creator. This is so cumbersome, time-consuming and expensive it is unworkable without a limitless budget. In The Travellers we had to digitally remove Coca-Cola and Shell signs from buildings and even make sure we didn’t photograph the Mercedes symbol on a car. A superb Polish film poster from 1947 (for the Australian film Eureka Stockade) was forbidden as the artist was dead and his heirs couldn’t be traced.

The effect of all these restrictions, which remove so many familiar images of everyday life, leaves the audience wondering on which planet the story could be taking place.

Attended a book launch in Balmain of Peter Fitzsimons biography of Weary Dunlop. Peter is the only internationally celebrated ex-Rugby player I know of who is also a best selling writer. His numerous biographies and histories (Breaker Morant, James Cook, The Catalpa Rescue, Burke and Wills, etc, etc) are often reviewed with the words ‘accessible’ ‘readable’ which I think slyly implies ‘lightweight’. A long way from the truth, I maintain. Not only are the books thoroughly researched but Peter’s opinions are thoughtful, balanced, astute – and certainly entertaining.

The extensive press and TV coverage of the famous Whitlam/Kerr dismissal incident 50 years ago rather took me by surprise, with opinions unsurprisingly landing heavily in Whitlam’s favour. I remember, in 1975, that many of my friends, certain that the election see a huge victory for Whitlam, were shocked, even outraged, that he lost.

A short time before the dismissal I was at the Sydney Opera House queueing for tickets and saw Gough Whitlam in the line. We had met when he perhaps rashly, and probably unwisely, agreed to appear in a scene in my Barry McKenzie film. He explained he was buying tickets for an opera he wanted to see and expressed surprise at my suggestion that, as Prime Minister, surely someone on his staff could have arranged for the tickets? ‘I like to select the seats myself,’ he said.

A man with style and charm.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.