It is de rigueur among our so-called knowledge classes to lament the fall of America. The refrain is familiar: the United States is in terminal decline, democracy is all but dead, and a narcissistic, authoritarian President stalks the stage, much like Hitler. Meanwhile, we are assured that our democracies – calmer, more civil, and less polarised – are working much better. The United States is consumed by chaos, while Australia and the other Westminster countries are supposedly models of health.

It is a comforting story, especially for the supercilious progressive left.

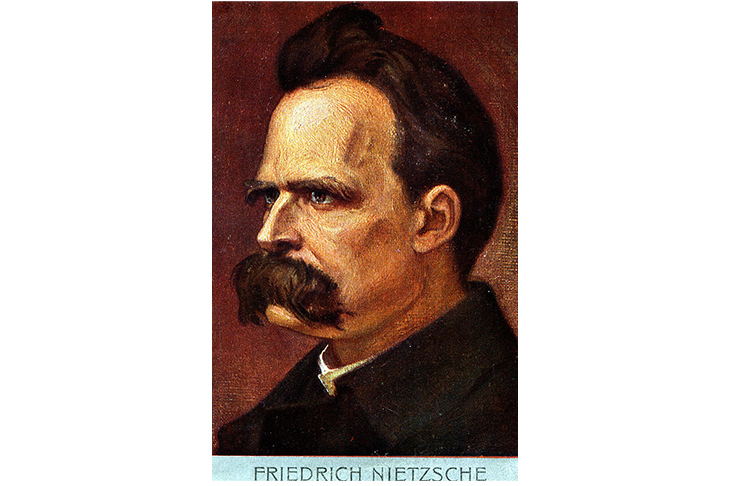

Yet, for all its dysfunction, America remains the one great democracy where the most important arguments are forced into the open. By contrast, Westminster democracies like ours risk sliding into what could be coined a ‘Nietzschean technocracy’: rule by experts, sustained by consensus and comfort, where the rough work of democratic conflict is outsourced. The paradox is stark: the United States looks sick, but it is still doing democracy’s hard yards – not just for itself, but for all of us.

Nietzsche, whose main works were published in the 1880s, distrusted the modern state even then. He described it as a ‘cold monster’ (Thus Spoke Zarathustra). He foresaw the bureaucratic expansion of power and the role of educated specialists in administering it. In The Will to Power he mocked the ‘objective man’ – the type of academic or expert who thinks himself value-free but is in fact servile to prevailing fashions and institutions.

Australia is increasingly a place where governments and technocrats muffle debates before they even begin. Consider three examples, from an increasingly large pool.

In South Australia, recent electoral law amendments ban political donations in a way that would be unconstitutional in the United States. They could even be unconstitutional here. They have been celebrated as a triumph of fairness, but the laws hugely limit freedom of political expression and entrench incumbents. There has been no debate – the Australian media, academy and chattering classes have not even blinked.

On the Voice referendum, every expert and institution lined up behind the proposal, assuring us it was inevitable and morally necessary. None of them stopped to examine unintended consequences or practical design. Platforms for legal debate – the lifeblood of constitutional design – were avoided and even shut down by some of our most senior lawyers. The Voice was defeated only by the common sense of all Australians, and a handful of people prepared to take on the cacophony of consensus from the expert class. Had it been left to the parliament, we would now have a constitutionally enshrined Voice.

On renewable energy, we were told by governments, rent-seekers and technocrats that the transition to large-scale renewables would be smooth, cheap, and inevitable. Yet if you question the now systematic obfuscation of the financial and environmental costs, or demand elementary mechanisms to ensure remediation and decommissioning, you are still a denier. The messier it gets, the more it is declared by experts to be beyond politics.

This is what a Nietzschean technocracy looks like. Nietzsche warned of the last man: the citizen who wants only comfort, safety, and entertainment, avoiding risk, striving, or any conflict. Francis Fukuyama adapted this warning in The End of History and The Last Man, suggesting that liberal democracy might indeed be the end point of ideological struggle – but that it could become less of a contest and leave mankind anaemic, unfulfilled, and, in a democratic sense, barely functioning.

Prominent political scientists like Colin Crouch (post-democracy) and Daniele Caramani (The Technocratic Challenge to Democracy) have diagnosed the modern version: politics is hollowed out, citizens disengage, and expert consensus closes off debate on issues that matter. While Fukuyama places faith in a properly functioning administrative state, Caramani and Crouch have diagnosed a drift into technocracy and post-democracy.

In Westminster systems, the trend is supercharged by institutional design. Without a bill of rights, free speech protections are statutory and fragile. Courts are deferential. Parliaments these days often bend to the fashion. It is easy for governments to narrow the contest and hand issues to regulators, tribunals and ‘experts’ who frequently take a too narrow and political lens to solving problems.

America, for all its flaws, cannot so easily shut down debate. Its Bill of Rights, especially the First Amendment, places speech beyond the reach of majorities. While Trump tests the limits of executive power to the extreme, the Supreme Court is a true bulwark: it has constrained presidents of both parties, Trump included, at every turn. Far from enabling authoritarianism, the Court has stopped many executive power grabs in their tracks. The recent and frankly ridiculous Trump forays into banning flag burning will be shot down in seconds by the Court, as it has before.

This is why debates on speech, identity, equality and executive power play out noisily – often painfully – in America. Chaos is the sound of democracy working, and since its founding, when America has convulsed the world has always watched – and learned.

Consensus and civility can be dangerous masks. We should ask: if debate on highly contested matters is smoothed over by reference to expert authority, is that still democracy in the full sense? Or is it the final manifestation of Nietzsche’s last man politics – a system that prizes harmony at the expense of vitality and truth?

Technocracy is not tyranny, but it is corrosive. It breeds distrust, narrows choice, and weakens resilience. It creates an illusion that democracy is functioning while the most important questions are decided elsewhere.

It is likely that in coming years, as America struggles with its internal divisions, historians and political scientists will debate with renewed vigour whether its 18th-century constitution is fatally flawed: whether too much power was given to a president resembling a monarch rather than to a prime minister accountable to parliament. And whether an entrenched bill of rights is simply too hot to handle for a modern administrative state.

Whatever the constitutional trade-offs, one fact remains: America’s system forces the contest. It drags arguments into courts, the Congress, and public squares, where they belong. It does not allow elites to declare matters settled.

Most Australians would prefer to live here than in America, but we should stop sneering at America and ask in all seriousness whether our relative quietness is in the longer term a greater danger.

In the end, as throughout history, America’s tendency to turbulence could be its saving grace.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.