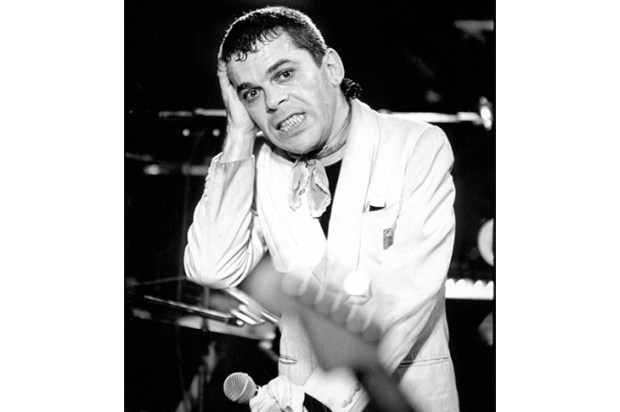

Charlie Kirk, founder of Turning Point USA and one of the most visible conservative activists of his generation, was shot and killed while speaking at Utah Valley University on 10 September. Kirk joins the grim company of those who have paid with their lives or bodies for refusing to soften their message.

Anna Politkovskaya, murdered in 2006 after exposing the brutality of Putin’s Chechnya campaign, became an emblem of what happens when gangsters seize the state. Salman Rushdie endured decades under a fatwa for The Satanic Verses before being stabbed in 2022 by an Islamist fanatic. He still carries the scars across his face and body – a living reminder of how far zealotry will go to silence words.

The contexts are different, yet the thread is recognisable. Those who stretch the boundaries of what may be said invite attempts to shut them down. Sometimes it is done with bullets, sometimes with knives, sometimes through the quieter mechanisms of political discipline.

Kirk’s murder represents the latest escalation in America’s growing political violence. His approach was deliberately confrontational: he carried conservative arguments into universities where the reception was hostile, and the atmosphere noisy and combative. Crucially, the events went ahead. Disagreement was endured, never treated as grounds for cancellation.

Through Turning Point USA, Turning Point Action, and a web of affiliates, he created something more durable than any speech: infrastructure for contestation. Conferences, campus chapters, and media outlets gave conservative students platforms in environments that often worked against them. His death silenced a career and destabilised a network built to expand democratic discourse. Authoritarian regimes go after precisely this kind of structure because it sustains the habit of disagreement.

Kirk was combative, yet his instinct was engagement rather than annihilation. He thrived on questions from hostile audiences, often letting critics speak at length before responding point by point. He did not expect synthesis, yet he insisted that disagreement could be aired without contempt. His model was to keep adversaries talking, even when consensus was impossible. That discipline of encounter – argumentative without being insulting – is what separates democratic conflict from the endless sneer of partisanship.

Kirk understood something many politicians forget: democracies require conflict. Arguments, however heated, reveal where societies strain and where they can bend. His campus debates forced both supporters and opponents to spell out their positions under pressure, producing information no focus group could ever supply.

Australia reveals how democracies can suffocate debate without firing a shot. The problem here comes from inside the walls. Dissent is often strangled before it has a chance to be heard.

Senator Jacinta Price discovered this when she remarked that high immigration tends to benefit governments in power – an observation well within the mainstream of political science. Like Kirk, Price’s approach was straightforward without being inflammatory, empirical without being accusatory. Instead of counter-argument, she faced censure from her own colleagues: opposition leader Sussan Ley and manager of opposition business Alex Hawke. The claim was treated as taboo-breaking rather than a hypothesis to be tested.

Representative Nancy Mace, speaking in the stunned hours after Kirk’s assassination, captured the principle at stake: ‘Just because you speak your mind on an issue, doesn’t mean you get shot and killed. In this country we have the First Amendment, we have freedom to speak what’s on our mind, and shouldn’t get shot because we believe in our system of democracy; conservative, liberal whatever you are….’

Mace’s words were meant for America, yet they resonate uncomfortably in Australia. Senator Price spoke her mind on immigration, facing colleagues who moved swiftly to shut her down. The mechanics differ; the reflex is the same: punish those who break from the authorised script.

That choice is revealing. Universities in America allowed Kirk to speak and absorbed the uproar. Australia’s conservatives move quickly to suppress conflict before it arises.

Hawke styled his rebuke as loyalty to the party, yet his instinct was to silence Price before her argument could gain traction – the reflex of someone who mistakes authority for argument. Anyone who has watched party rooms closely knows how easily ‘loyalty’ becomes a pretext for shutting down debate. His fear was that difficult truths might be heard, that voters might notice disagreements exist inside the Liberal party.

Ley’s intervention carried a different flavour. Where Hawke acted the enforcer, Ley presented herself as custodian of respectability. Condemning Price gave her a way to polish her credentials as modern and moderate. Opportunism has consequences. Younger MPs learn the lesson: avoid speaking candidly on sensitive issues or risk internal punishment. Over time, silence hardens into habit.

Price’s treatment fits into a larger sequence. Katherine Deves was cast out for raising concerns about transgender participation in women’s sport, a subject openly debated in Britain and America. Senators who question the economic toll of net-zero policies – figures like Matt Canavan and Bridget McKenzie – are quietly sidelined. Each case follows the same script: isolate the dissenter, avoid the substance, and gradually contract the boundaries of acceptable discourse.

This corrosion is subtler than noisy protests outside a lecture theatre. A mob can jeer yet it cannot decide whether an event goes ahead. When suppression comes from inside the party, it carries the weight of authority.

The difference between robust and fragile democracies lies here. Robust institutions absorb the noise; protests and counter-speeches are tolerated, and society learns something about its own divisions. Australia is drifting the other way. Hawke and Ley reveal a political class uneasy with conflict, preferring to perform unity rather than grapple with difference. It looks tidy, yet it is brittle.

This narrowing comes just as the country faces pressing challenges: immigration, climate transition, social policy, demographic change. These demand honesty and argument. Instead, politicians signal that certain observations must never be spoken. That breeds self-censorship and robs the public of the debate it deserves.

Hawke and Ley illustrate this decay. They confuse party management with public duty. They appear strong while hollowing out the very process that makes democracy resilient.

The comparison with Politkovskaya and Rushdie may feel stark, yet the reflex is recognisable. Wherever speech unsettles, the instinct is to remove the irritant. The weapons change. The logic does not.

Australia’s conservatives are edging toward the habits of the very forces they claim to resist. They echo Putin’s gangster reflex, the censorious fury of Islamist fanatics, and the punitive zeal of campus radicals. Different tools, same desire: stop the conversation rather than face it.

This makes Kirk’s example stand out even more. In an era where supposed darlings of the left operate as ideological megaphones, mistaking provocation for dialogue and branding for argument, he carried a recognisably dialectical impulse. However sharp his words, he treated disagreement as an opportunity to keep a conversation alive, never as a chance to terminate it.

Kirk’s death showed what silencing looks like with bullets. Australia demonstrates how effectively it works with bureaucracy. Both erode the culture of liberty. Both leave a society less willing to hear itself speak.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.