Like the characters in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, it seems that when the Labor party is voted into government, it swears off vice. For the King of Navarre and his merry men that vice was the company of women (women’s company was just too good – not that women themselves were the vice). For the ALP, it seems, it is the company of comedians.

Now while Shaun Micallef is definitely a man afflicted by the ability to create trouble around every corner and Chris Lilley seems to have broken every rule in the woke handbook of conniving offence, it is difficult to understand what necessitates the comedy hiatus at the ABC when the likes of Rudd, Gillard and Albanese arrive at the Lodge.

It was not always so. When Whitlam entered Canberra in 1972 astride his white charger, Reform, Australians had the good fortune to have been subtly prepared for the wild ride by the Aunty Jack Show, which had premiered a few weeks before. While not political comedy, its bearded, boxing, motorcycling transvestite was a sight for sore eyes for a country still fighting the Viet Cong and trying to understand the implications of second-wave feminism.

Max Gillies took the political satire genre on TV in Australia to new heights in 1984 with his highly talented ensemble (which included John Clarke) in the Gillies Report. Gillies was equally adept at sending up the self-importance of Bob Hawke or Andrew Peacock and managed to milk the impressions gag cow for all it was worth, sharpening his pen and applying his make-up to lob grenades at the likes of Neville Wran, Russ Hinze, David Lange and Kerry Packer. The format was resurrected as the Gillies Republic and Gillies and Company until 1992.

The short-lived Dingo Principle, created by Patrick Cook and Phillip Scott in 1987, was a touch rhapsodic for my tastes at the time but had the singular distinction of creating diplomatic headaches for ABC supremo David Hill, and Michael Duffy, the then minister of communications.

The show lampooned Ayatollah Khomeini in a mock interview that got two Australian diplomats expelled from Tehran. This month, we finally got our revenge – Tehran’s man in Canberra was shown the door. The irony will be lost on Labor’s woke advisors, of course; they don’t even know the context of why our diplomats were expelled in the first place. It also put the boot into Mikhail Gorbachev and Vladimir Lenin, leading to a strongly worded letter from the USSR’s Canberra press attaché reminding Comrade Hill that Lenin’s name was cherished by millions around the world, including in Australia.

Hill must have believed him, having had first-hand experience of dealing with the Australian Railways Union in his previous job as head of the NSW State Rail Authority.

The ABC had some wonderful, not quite political but politically aware, comedy in the late-Eighties and early-Nineties, with the Big Gig and DAAS Kapital. Keating’s ‘recession we had to have’ seems to have put a downer on political comedy and the next iteration was Peter Berner’s incisive Backberner which ran from 1999 until 2002.

Smack bang in the middle of Howard’s reform agenda, Backberner made the Gareth Evans and Cheryl Kernot saga, unimaginable to most, engaging and well, real. By real, I mean, ‘Really? They did what?’ Kim Beazley’s natural gormlessness made for easy pickings for Berner as Bill Shorten’s was to provide for Shaun Micallef in Mad as Hell, a decade later.

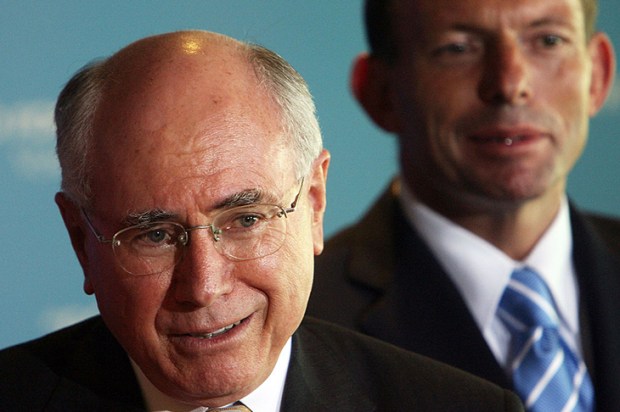

Berner’s easy gags were just what Australians wanted and they didn’t need to be fancy: ‘George Bush underwent a colonoscopy recently, or an IQ test, depending on how you want to look at it.’ ‘John Howard is called the prime minister because he is only divisible by himself and one.’ Satire was used to good effect to highlight the perception that Howard’s policy of turning back the boats was uncaring. A Hugh White-inspired defence analyst character was happy to observe that Australia was only under threat of invasion in 2002 by groups who had the decency to sink a few hundred miles before making landfall.

It’s hard to overstate the value of shows like Backberner or Mad as Hell in stimulating a scepticism of untrammelled and unquestioned political decision-making. Despite Micallef’s foray into politics with Newstopia, Berner’s show wasn’t really repeated again until Mad as Hell debuted in 2012. John Clarke and Brian Dawe’s brilliant, short weekly satires on the 7.30 Report filled the gap between Berner and Micallef, but theirs was one that was not widely accessible. The Chaser programs had moments of inspiration too, at the end of the Howard era. Unlike the Chaser, Clarke and Dawe never expected politicians to act more honourably than spivs on a gravy train. Perhaps that is why they never lost the irony that made their material so priceless.

In 2018, Scott Morrison quipped Mad as Hell needed to be exempt from ABC budget cuts– a small but telling act that revealed how conservatives often see comedy as a natural human expression. The current crop of Labor politicians, by contrast, seem to treat satire as dissent – a destabilising force that must be contained if it threatens their progressive project.

That outlook has shaped the ABC itself. Where satire once pushed boundaries and provoked uncomfortable laughter, it is now treated as a liability rather than a strength. Chris Lilley built his brand on equal-opportunity piss-taking. His humour was risky, deliberately provocative and boundary-testing in ways that once defined ABC comedy. After the brouhaha over Jonah from Tonga and the blackface character Smouse in Angry Boys, the mandarins appear to have decided that such risks are no longer worth taking.

Mad as Hell finally came to the end of its tether in 2022, not with scandal but by Micallef’s own decision to step aside. What has followed is telling. In 2024 he returned with Eve of Destruction, a limp parlour-game chat show where celebrities are asked what two items they’d save if their house were burning down. It is television as blancmange: wobbling, sweet, instantly forgettable. The sharpest satirist of his generation has been reduced to cultural pudding, and the ABC seems perfectly happy with that.

Previous Labor governments in the dinosaur age of Whitlam and Hawke were made up of people who understood the Australian tendency to punch up with their larrikin humour and to celebrate the quirkiness that attaches to our social identities. Not all ‘bogans’ are stupid and not all ‘blue bloods’ can justify their place in a social hierarchy. Australians have always known this and our ingrained sense of fairness has allowed us to create a particularly open society, one that celebrates difference even if it does not always understand it particularly well.

I hope that the demise of Mad as Hell –and its replacement by cultural blancmange – is not accompanied by another five-year hiatus where we wait and wait for someone to hold a mirror up to our political leaders. The conservative side of politics has shown itself particularly tolerant of the shout ‘The Emperor has no clothes’. Labor, by contrast, seems to think Australians will be safer if the court jester is locked in the basement.

That betrays a tin ear for who we are. Australians don’t need to be protected from satire – we thrive on it. Our sense of irony is what stops politics from tipping into pomposity. The notion that conservatives pose some looming danger to a decent, caring democracy is not just misguided; it’s the sort of misreading you get when you’ve stopped listening to the laughter of your own people. We are still waiting for the real Australia to return – the one that can laugh at itself, even when the joke hurts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.