How many police officers does it take to charge an elderly and ailing man of 83 who is accused, as one complainant put it of ‘going the grope’? One? Two? Three? According to an eyewitness, around 30 police officers burst into the apartment of Alan Jones and charged into his bathroom where they arrested him while he was getting into the shower.

Why were so there so many officers? Did they want to have a sticky beak at his digs in the famed Toaster building on Circular Quay? Did they want bragging rights at cutting down the tallest poppy on commercial radio for several decades? Were they worried that if only two officers turned up they wouldn’t be safe with Jones?

Not only does Alan Jones have no history of violence of any sort, none of the alleged offences involved violence. Indeed, none of the complaints are alleged to have occurred in the last five years – the most recent dates back to 2019. Since then Jones has been repeatedly in hospital enduring lengthy operations.

If thirty police officers pouring into Jones’ residence sounds like a suboptimal use of taxpayer resources that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

For nine months a ‘top-secret’ child abuse strike force has devoted its working hours to investigating Jones yet hasn’t found a single allegation of child abuse. Not one. According to the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, anyone who reports a sexual assault and is over the age of 16 is categorised as an adult whereas the youngest person to lodge a complaint about Jones was 17 at the time of the alleged offence.

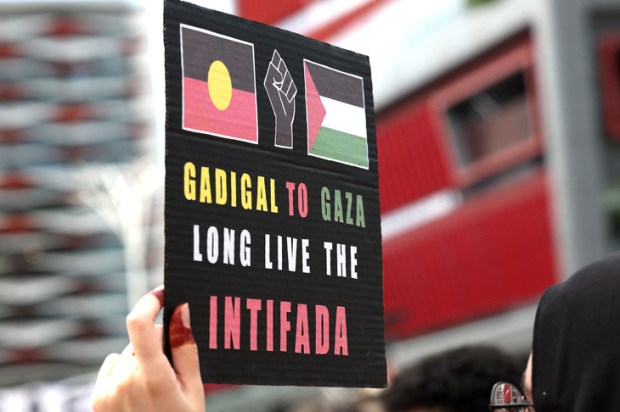

Yet that’s not the end of this extravaganza. Assistant Police Commissioner Michael Fitzgerald decided to devote more police resources to a media conference to discuss the morning’s jamboree. The police did not call a media conference to denounce an antisemitic rampage a few days later, for example, or when Mohommed Farhat, 20, was arrested at Sydney airport attempting to flee the country and charged with 21 offences related to the rampage.

Why did the Commissioner single out Jones? He didn’t say but we should perhaps be grateful that he doesn’t do it on every occasion since, according to the most recent statistics, in the twelve months to June 2024 there were 8,474 recorded incidents of ‘sexual touching, sexual acts and other sexual offences’, the category of charges levelled against Jones.

What Commissioner Fitzgerald and Detective Superintendent Linda Howlett did say was how ‘brave’ the ‘victims’ were, commending and thanking them ‘for the courage that they have shown in coming forward and reporting to police’. Not once were they referred to as ‘alleged victims’ or ‘complainants’. It was as if the onus of proof had been reversed and what Jones was afforded was the presumption of guilt.

Fitzgerald did concede that the ‘victims… are fully aware, as are the investigators, that the hard work is just beginning and they have given their statements fully aware that they will go before the courts’. This seemed to be the only veiled reference to the fact that the veracity of their statements still had to be tested in a court of law but Fitzgerald left no one in any doubt that a crime had been committed and he stood by the injured parties saying, ‘The victims have our full support,’ he said, ‘as do all victims.’

The Judicial Commission of New South Wales takes a more orthodox approach. In the Criminal Trial Courts Bench book it points out that, ‘A critical part of the criminal justice system is the presumption of innocence.’ It explains that what that means is that ‘a person charged with a criminal offence is presumed to be innocent unless and until the Crown persuades a jury that the person is guilty beyond reasonable doubt’. Perhaps Assistant Commissioner Fitzgerald and Detective Superintendent Howlett could take a look. Not once in the travesty of a police media conference was Jones afforded the vaguest semblance of the presumption of innocence.

The Criminal Trial Courts Bench book also observes that to prove the accused is guilty of sexual touching, for example, the Crown must prove ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ each of the four elements which make up the offence; that ‘the accused’ ‘intentionally’ touched ‘the complainant’; that ‘a reasonable person’ would deem the touching was ‘sexual’; that ‘the complainant’ did not ‘consent’ to being touched; and that ‘the accused knew the complainant did not consent’.

It should be obvious but it seems not to be, at least to the police, that if they ignore the presumption of innocence it doesn’t just make it difficult if not impossible for the accused to get a fair trial, it undermines confidence in the justice system as a whole. Perhaps they don’t care.

When asked about the gravity of the charges against Jones, the Assistant Commissioner replied, ‘All charges that go before the court are serious.’ Yes, but why are the scarce resources of a specialised Child Abuse Squad (CAS) being used to hash over decades old allegations of men groping men? The squads are meant to ‘prevent, disrupt and respond to… sexual abuse, serious physical abuse or extreme neglect of children aged under 16 years’.

Meanwhile, the most recent statistics show that in 2022 to 2023, there were 45,400 Australian children who had been, are being, or are likely to be, abused, neglected or otherwise harmed of whom 13,700 were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare).

Bryan Wrench, one of the lawyers defending Jones is no stranger to child abuse cases. In 2018, he defended the Cook family, seven of whom were arrested over the alleged sexual abuse of three children. The children claimed they had suffered repeated abuse including extreme sexual assault, torture and blood rituals that were filmed and photographed. In the absence of any physical evidence, (no signs of injuries, DNA, videos, photos), the police based the entire case on the word of the children, one of whom admitted to his mother that he was lying. The accused were incarcerated for between four and seven months and repeatedly denied bail. It took Wrench two years but he got all 127 of the horrific charges dropped. He described the police behaviour as a ‘witch hunt’ and the case as ‘one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in New South Wales’. The lesson, he said, was, ’When you’re chasing monsters, make sure you don’t turn into one.’ But is it a lesson the police have learned?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.