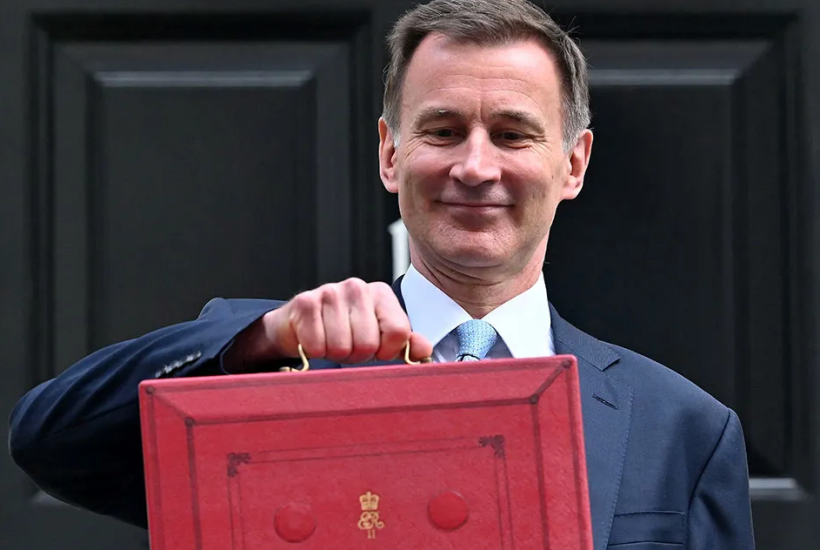

Is Jeremy Hunt’s ‘British Isa’ worth having? The new £5,000 tax-free allowance for UK equity investment comes on top of the existing annual £20,000 Isa limit, so on the general principle that it makes sense to maximise tax-efficient savings, the answer might be yes. But will it achieve the Chancellor’s aim of allowing patriotic savers to buy into the growth of ‘the most promising UK businesses’ while supporting them with capital to expand? To that, I’m afraid, the answer from the professionals has been a resounding no.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in