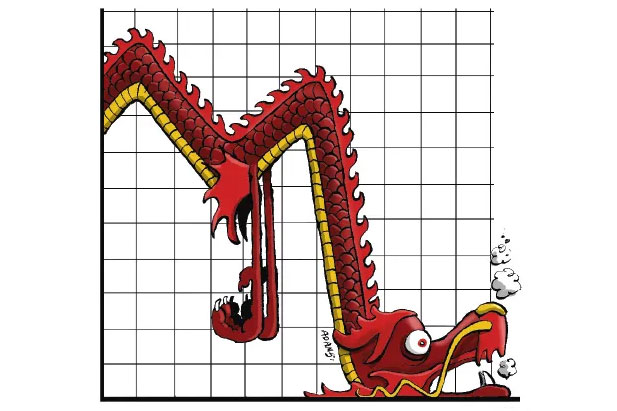

The future trajectory of the Chinese economy is a subject for doctoral theses rather than casual column items. But the advent of the Year of the Dragon, at last weekend’s Lunar New Year, was greeted with such pessimistic commentaries that the natural contrarian should ask whether the consensualists are getting it wrong: maybe the dragon is merely marking a pause before martialling its mighty resources for the next transglobal burst of fire?

The negative narrative goes like this.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in