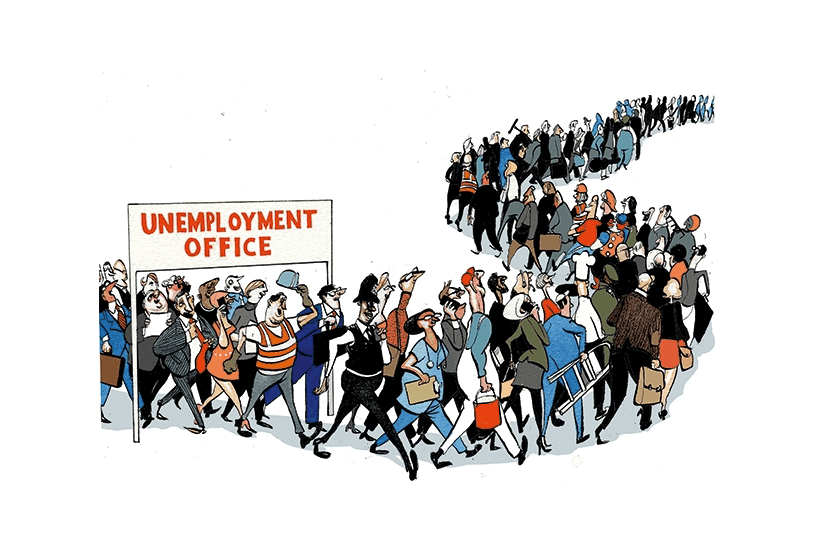

Britain’s unemployment statistics are unreliable, and the Office of National Statistics is experimenting with a new method of counting the number of people out of work. Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, said as much this afternoon while giving evidence to the House of Lords Committee on Economic Affairs.

Until the 1990s the unemployment figure was a simple count of the number of people who were claiming unemployment benefit. Since then, however, the figures have been collected via the Labour Force Survey, which is a questionnaire put to a sample of households. As Bailey says, the size of this sample was already shrinking before the pandemic, making the figures more volatile. Then, the Labour Force Survey moved from face-to-face to telephone interviews. ‘The problem is generally that as a nation we don’t answer the phone if we don’t know who is on the other end.’ As a result of this and a further shrinking of the sample size, says Bailey, ‘whether unemployment is 3.8 per cent or 4.2 per cent is really hard to judge’. And when you are setting interest rates that rather matters – although it perhaps doesn’t explain why the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee was so slow to raise interest rates in 2021 and early 2022, failing completely to see the inflationary forces which were building.

The ONS, he says, is now working on a new method of measuring joblessness which should help to bring unemployment and economic inactivity together. He didn’t, however, expand on what that would be. But if, as he says, the new system will be rolled out later this year it will not be without controversy if the election ends up being fought against the background of joblessness figures which have suddenly dramatically worsened.

As The Spectator has observed many times over the past few years, if you look at the unemployment figures alone Britain appears to be enjoying a jobs miracle. But that vanishes when you look at the figures for the number of people claiming out of work benefits, which, as revealed here this week by Michael Simmons, has reached a record of 5.6 million. The problem is masked thanks to the growing numbers of people who are claiming Universal Credit and who are not obliged to look for work. For the two decades until 2019 the number of people registered as long-term sick steadily declined. Yet over the past five years – and starting a little before the pandemic – it has surged to reach a record of 2.8 per cent.

But you would know nothing of this if you were looking purely at the official unemployment statistics, which show it at a near 50-year low of 3.8 per cent. We are back to the bad old days where people were shunted onto long-term sickness benefits to massage the unemployment figures – at a price of condemning people to long-term welfare dependency. This is exactly the problem which Universal Credit was supposed to reverse, but instead seems to have been made worse. It is just that it has been hidden by an apparent reluctance on the part of unemployed people to answer the telephone.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in