This time next year, Darren Jones could very well be deciding how your tax money is spent. As shadow chief Treasury secretary, his days are spent having difficult discussions with would-be Labour ministers and explaining that it would be hard for them to spend any more than the Tories already are. If Labour wants to change Britain, the party will have to rely on reform rather than cash. This message would be a theme of Keir Starmer’s government, in which it is assumed Jones would be a key player.

In his office, Jones, who is 37, has a framed front page proclaiming Labour’s 1997 election victory. Next to it hangs a picture of the Bristol council house he grew up in. He didn’t have ‘much of a view’ about Labour’s victory at the time (he was ten) but he now says it changed his life, because it was a New Labour policy which took him from one of the worst-performing schools in England (Bristol’s Portway Community School) and put him on the fast track.

‘It was the Gifted and Talented programme which plucked people like me out of the system and gave us opportunities to go to university, which no one in my family had done before,’ he says. ‘And the national minimum wage had a huge impact on my family. So I’ve got that sense of debt to the last Labour government.’ And to Blairites in particular: Brownites resented the Gifted and Talented scheme (an initiative which identified young and gifted individuals ‘significantly ahead of their year group’, who then received enhanced educational opportunities). Ed Balls regarded it as elitist and abolished it in 2010. By that time, Jones was moving from law to politics.

‘We must get out of the habit of thinking that a billion quid is not a lot of money’

Elected to Bristol North West in 2017, Jones rose to prominence as chair of the House of Commons business and trade committee, grilling his subjects for the cameras with theatrical flourish. His successful performances led to headlines, TikTok moments and, four months ago, a shadow cabinet seat. But it took him a while to ease into the role, he says. At first he was too lawyer-like – dry and unmemorable.

‘We were doing lots of heavily detailed reports. Great for policy wonks, but they weren’t really having any impact. So I took a breather and spoke to some other colleagues and I was like: what can we do differently?’ Labour veteran Margaret Hodge gave him the answer: ‘You have to think how the first question lands in the six o’clock news. So you’ve got to be punchy, to the point and land it well.’

He quickly scripted a question for the P&O Ferries executive who had just overseen the sacking of 800 British staff, asking him: ‘Are you in this mess because you don’t know what you’re doing? Or are you just a shameless criminal?’ It worked a treat, although Jones says he struggled at times during the rest of the session. ‘You then had to keep a straight face while staring at him directly, while the cameras were paying attention to you – which is quite difficult to do.’ He keeps up the inquisitions in his new job, but, he says, in a friendlier way. ‘I just have to ask colleagues, as opposed to ministers. And in a private setting, not on TV.’

Is he having to say ‘no’ when they ask permission for high-spending policies? ‘Well, yes and no,’ he says. ‘The question is: how can we get to the right answer together? We want to be helpful, we want to be reforming. We might be able to get you to the same or a similar place in a different way, so we should talk about it. My two buzzwords are “growth” and “reform”. Most of the work is anchored onto either of those. I want to be a reforming chief secretary to the Treasury.’

What was Sir Keir’s message to him when he offered the promotion? ‘He knew that the economy was going to be front and centre of the general election campaign and thought that I’d be someone who would be a good voice and a good kind of leader in that space,’ Jones replies. ‘He said “look, this is not an easy job that I’m asking you to do but you’re in the middle of it with me and Rachel [Reeves] making these decisions and we’d be happy to have you’”.

He pins a lot of hope on cutting waste, and wants to create an Office for Value for Money as a ‘hit squad’. ‘The way we deliver public services has to be modernised because the amount of money that is wasted on inefficiencies adds up to many, many billions. We’ve got to be able to claw that back.’

One growing cost awaiting whoever wins the next election is a surge in welfare. The disability benefit caseload is projected to rise to 920 people a day for the next five years. Is some radical reform needed here? It’s hard to tell, he says, due to a dearth of information on who is being signed off sick and why. ‘We don’t know from a Whitehall perspective who these people are, where they are and what interventions might help.’

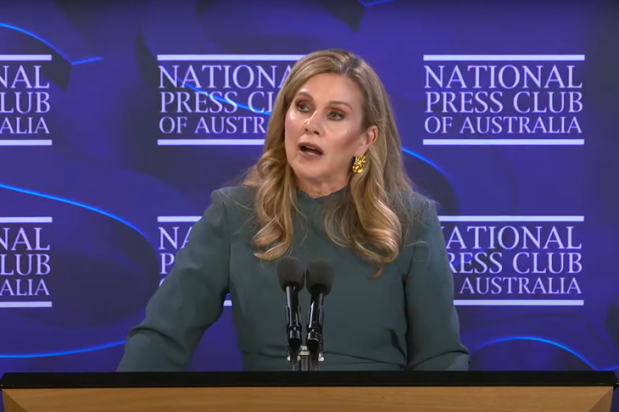

Darren Jones (PA Images)

Darren Jones (PA Images)

His office in the Commons is next door to that of another would-be Labour reformer, Wes Streeting, the shadow health secretary. ‘He talks about this stuff all the time –prevention vs treatment. Now, my job is to try to help Wes and the health team be in the best possible position to be able to effect those reforms that he wants to put in place.’

Jones says that the money raised when Labour abolishes non-dom status will be sent to the NHS. But does he think the £1 billion it’s expected to raise will even be noticed in a £170 billion-a-year NHS? ‘We must get out of the habit of thinking that a billion quid is not a lot of money,’ he replies quickly. ‘The problem we have is that there are billions here, billions there, billions everywhere in government that are wasted.’

If a billion is a lot, what about the £28 billion the party has said it will spend to fund its green prosperity plan? His boss, the shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves, announced the plan two years ago but has since cooled, saying it would happen only if it meets Labour’s debt rules (not to borrow to fund day-to-day spending and to reduce national debt as a share of the economy). Starmer and Reeves are expected to discuss whether the policy could be diluted further in the coming weeks.

Some in the Labour party think £28 billion is laughably unaffordable, but what does Jones think? ‘If we are successful in growing the economy in the way that we think we will be, then that creates the room for more investment,’ he says. ‘If we’re not, the fiscal rules come first and are non-negotiable.’ This is becoming the standard Labour answer: money will come not from taxes or debt, but efficiencies and growth. How then would Labour grow the economy without making serious cuts to tax or regulation?

‘Public-sector subsidy isn’t what grows the economy,’ he says. So what does? He hopes that private companies will start to invest under Labour, encouraged by the end of Tory psychodrama and the emergence of stable Starmer. ‘We are calling it a stability premium,’ he says. ‘But we hear that from investors, we don’t just make that up. It’s what people have been telling us that they need and want in order to unlock investment.’

Say that Labour’s ‘stability premium’ works and the economy grows, would the government seriously spend £28 billion a year, as per Reeves’s original pledge? ‘The important question, though, is why 28 and what does that mean? That number was originally decided in 2021 when Rachel and Ed [Miliband] announced it at conference and there were two bits that underpinned that.’ Since then, he says, two things have changed. First, borrowing costs are much higher. Second, there is now more information about the work that needs to be done to reach net zero.

‘The National Infrastructure Commission has done its five-yearly assessment, which came out maybe two months ago, which made it very clear that there is plenty of private-sector capital and most of the infrastructure will mean using that.’ The new information, he says, emphasises private capital more than state subsidy. ‘I think a big test of the next Labour government, if we are to win the election, is how successful we are at unlocking that private-sector capital and that investment.’

‘The fiscal rules come first and are non-negotiable’

Should that fail, can Jones promise taxpayers won’t have to stump up? This is how the Tories plan to attack Labour in the general election campaign – they will say that Labour’s plan will lead to huge borrowing costs or higher taxes. ‘We have said we recognise that the tax burden on working people is the highest it has been for a very long time, so we want to see tax coming down for people,’ he says.

He points to Labour’s support for Sunak’s recent National Insurance cut as proof of ‘our inclination around the tax bill – we want it to come down. But only when it is affordable to do so.’ This sounds like the old Cameron refrain: ‘stability before tax cuts’. What about further windfall taxes? ‘The current windfall tax does fall into the next parliament,’ Jones says. ‘Of course we will have to do a Budget if we win the election, obviously it will be for the chancellor of the day to announce any tax policy at that stage.’

Jones has already made history in the Commons: he is the first MP to be called Darren (‘Apparently the only name that is dying out more quickly is Nigel’). But what he would really like to be remembered for is helping return Labour to power after 13 years .‘Tony and Gordon have both been very generous with their time and their support over the years, but we need more Labour prime ministers and former Labour prime ministers.’