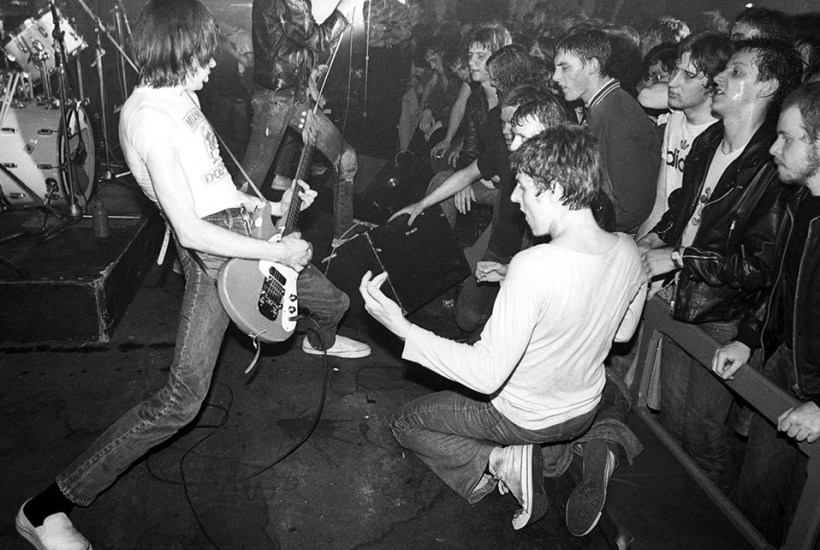

‘If any journalist asks you about the Beatles because you’re from Liverpool, say you hate them and you don’t listen to that old crap.’ Such was the advice that the DJ Roger Eagle, promoter and founder of the legendary (and there really is no other word for it) Merseyside punk club Eric’s, dispensed to a young Ian Broudie in the late 1970s.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in