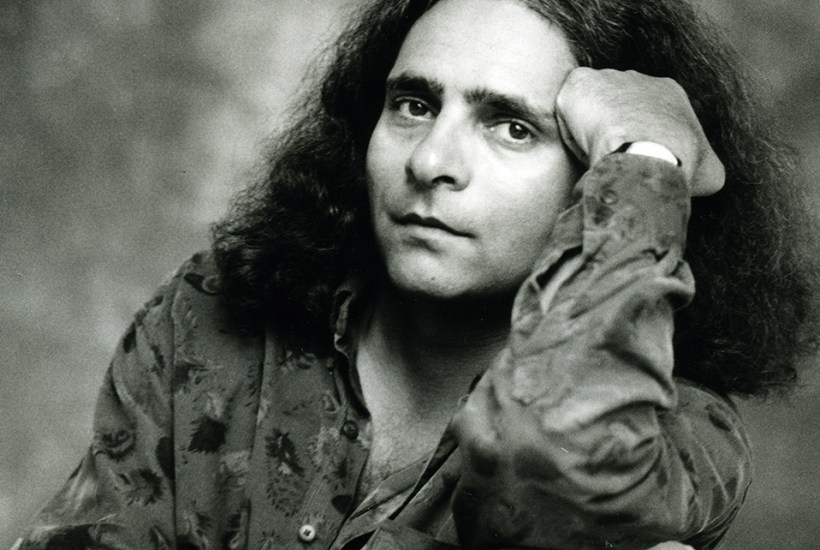

If any novelist, playwright or screenwriter of the past 40 years could be called ‘a writer of consequence’, to use the literary agent Andrew Wylie’s term, it would be Hanif Kureishi. While not shifting units on the scale of his near contemporaries Ian McEwan, Martin Amis and Salman Rushdie, Kureishi’s cultural influence – through his explorations of race, class and sexuality in novels such as The Buddha of Suburbia and films like My Beautiful Laundrette – is inestimable.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in