Kyiv

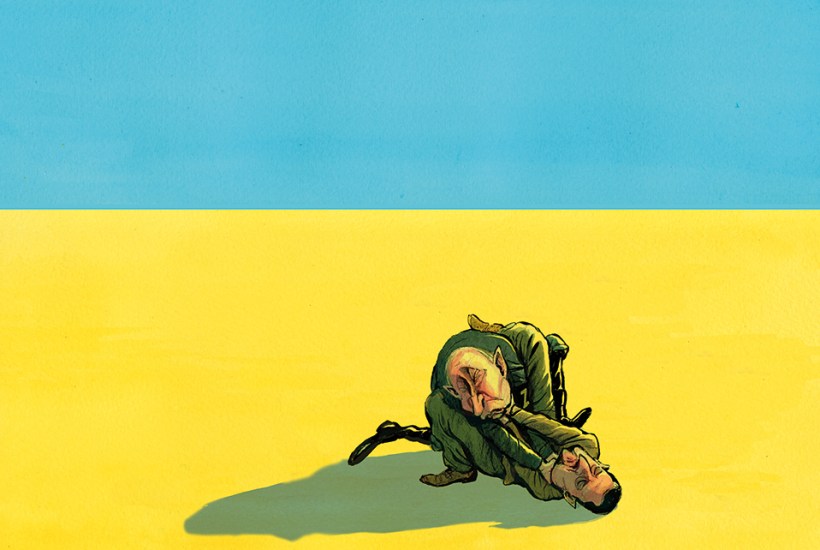

In Ukraine, the political mood has become sombre and fractious. As the front lines settle into stalemate, Russia ramps up for a new season of missile and drone attacks, and vital US support for Ukraine’s war effort crumbles under partisan attack in Congress, one existential question looms large. Should Volodymyr Zelensky continue to fight endlessly in pursuit of a comprehensive defeat of Russia which may be unattainable – or should he consider cutting his losses and reaching a compromise?

At the war’s outset, the Ukrainian President had a clear answer.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in