‘These things start on my birthday – like the Warsaw Uprising – and spoil my day,’ wrote the understandably self-pitying Barking housewife Pat Scott in her diary on the first day of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. ‘And then to spoil it more, Ted [her husband] took his driving test for the second time and failed.’ It is clashes like these, of the personal and humdrum against the political and global, that make David Kynaston’s close surveys of Britain in the second half of the 20th century such fascinating and lively documents. Yes, the world might be about to end, but that was no excuse to spoil Pat’s 37th birthday.

In the eighth book in his social history series Tales of a New Jerusalem about Britain from 1945 onwards, Kynaston takes 600 pages to cover just two years and four months, from 6 October 1962 (just before Cuba) to Churchill’s funeral on 30 January 1965, after which, commented the Observer, Britain’s era of importance and grandeur was over, and it woke up in ‘the coldness of reality’, with ‘the status of Scandinavia’.

So, with this brick on your lap, sit back and brace yourself for discovering what happened on pretty well every one of those 847 days. You never know what’s coming next, in Kynaston’s marvellous, long, semicolon-divided paragraphs describing a typical single weekday on which, for instance, Margot Fonteyn danced at Covent Garden with Nureyev for the first time, Dennis Lee in Yorkshire paid his first visit to a Chinese restaurant, the first supermarket in Carlisle, Fine Fare, opened, and Mr R. Stockting, the owner of Gillott Lodge Hotel in Edgbaston, stated: ‘I do not take coloured guests because it is a small, compact hotel, and in a family atmosphere such as we have, it would be embarrassing to us and to them.’ Reading this book is like putting your arm into a lucky (or sometimes unlucky) dip of the recent past. What nugget or stinky detail will come out next?

You might think you don’t want to know that, for example, ‘on Tuesday afternoon, there was a thickening fog in Chingford’ – but I assure you, you do. This (in late October 1962) turned out to be the last ever pea-souper, 12 years after the Clean Air Act. During it, 106 people died, a mink coat was stolen from Swears & Wells in Kensington High Street, Churchill groped his way to dinner at the Savoy and the Duke of Norfolk was stranded in a plane circling London Airport.

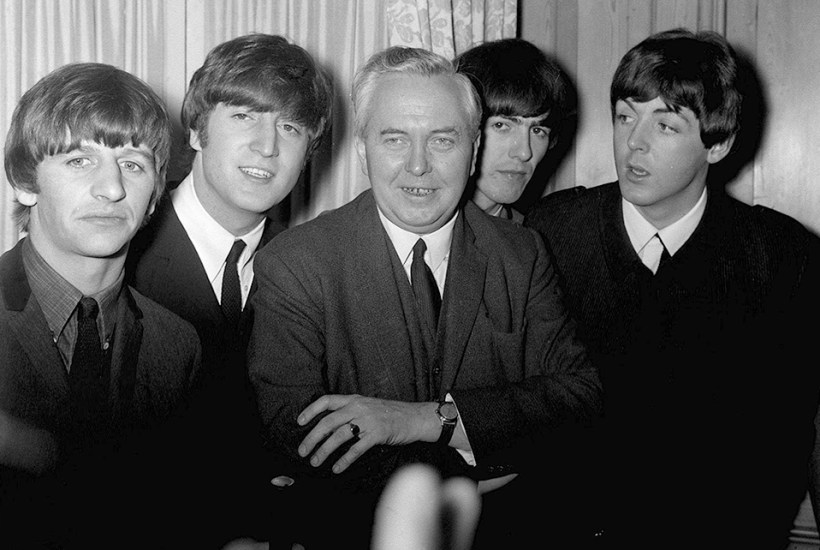

While sometimes playing the game of ‘which detail would I have cut from this long paragraph to make the book shorter?’, I relished the randomness of Kynaston’s gallery of Britain in the early 1960s, in which he masterfully juxtaposes the big events – Cuba, J.F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Profumo Affair, the Beeching cuts, the dawn of comprehensive schools, Beatlemania, the boom in high-rise building and the country’s gradual swing towards Labour – with the daily concerns of ordinary people. I imagined him thinking again and again ‘I simply can’t bear to leave that detail out’, even the diary entry: ‘Rained. Cold, miserable day. Made Christmas pudding.’

The humdrum details include the diarist Madge Martin choosing ‘the safe roast turkey’ during her first visit to a Chinese restaurant in Oxford and Philip Larkin complaining to his girlfriend Monica Jones after visiting his mother on Christmas Day 1962: ‘I don’t think I did anything I wanted ALL DAY except go to the lavatory.’ These are actually more illuminating of the feel of the period than the officially important details, such as the oscillating polling figures during the long run-up to the 1964 general election, which do rather go on and on. I think the sentence I would have cut from that extended section would be: ‘Next day, with the Tube strike in its final stages, David Bruce, the American ambassador, weighed up the electoral possibilities.’

We see a Britain on the cusp of the high-rise and shopping-centre age. While some families were still huddling round the wireless listening to the play on the Third Programme, or GPs were still saying to patients ‘Come in and have a cigarette. What’s the trouble?’, towns were being bulldozed. The phrase I came to dread most was ‘inner ring road’. ‘Don’t do it!’ I begged. ‘Don’t flatten Kingston-upon-Thames, or Newcastle, or Birmingham, or Sheffield to build your utopia for cars.’ But they did. It is astonishing how few complaints there were: even the Northern Architectural Association didn’t object to the proposed (and soon carried out) destruction of the 1820s gem Eldon Square in Newcastle. Kynaston doesn’t often bombard us with his own opinions, but after quoting an enthusiastic article in the Surrey Comet on the plans for the Kingston one-way system, he writes: ‘Of the destruction of a perfectly pleasant, intimate area, of the unrivalled concrete ugliness of the car parks, of the harsh and sometimes frightening wind-tunnel effect, and of the general soullessness, not even a hint of anticipation.’ But then he quotes the young housewife Rosina Vaughan thrilled with her new high-rise council flat. ‘Just fancy me with a stainless steel draining board.’

It’s salutary to be reminded how popular The Black and White Minstrel Show was: favourite entertainment for the family. Questions were beginning to be asked about its suitability. The producer defended it in what would now be a career-ending few words: ‘Blacking up is equivalent to clown’s make-up and is all surely traditional entertainment. The show is pure fantasy, like golliwogs. So what is wrong? It has nothing whatever to do with undermining the Negro.’

Small incidences of everyday racism keep bringing one up short. A diarist described the labour exchange in London N5 in May 1963: ‘One tall West Indian man in a cap and long coat, holding an attaché case, was sent from queue to queue: no clerk spared him a moment.’ Meanwhile, the Daily Mirror ran a piece called ‘How to Spot a Potential Homo’. And Pat Scott changed her washing powder from Omo to Fairy Snow. I needed to know all this. Each detail adds to the truth about the still quite unhappy Never Had It So Good era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in