At a time when almost everything gets worse, it is nice to recount that this State Opening of Parliament was better than the last one. Last year, there was a wintry sense of fin de régime, as the Prince of Wales stood in for his ailing mother. Now that Prince is King. Everyone wanted it to go well for him, so it did. There was a feeling of excitement, and perhaps relief that the chilly hand of rationalisation has not used the new reign to tighten its grip. The ceremony was, in a way, grander than under Elizabeth II, because we now have both a King and a Queen. For the first time since 1950 (King George VI was too ill to deliver the speech in 1951) two trains were required and so – to avoid a train-crash – more pages.

In case the whole thing gets Starmerised, I feel it worth recording for posterity the atmosphere of such occasions. They are both impressively stately and oddly intimate. The Chamber of the House of Lords looks splendid but is actually quite small. It has a hugger-mugger feeling. Except for the dramatis personae, peers must find a seat where they can, some stuck on benches supported by no backs for more than two hours. There is a curious box in the far corner in which the eldest sons or daughters of peers (including, this time, our daughter), are penned standing throughout, like guillotine candidates in a tumbril. In addition to the two principals, many of those present looked splendid too: a bewigged Scottish judge with red crosses all over his robes; the bishops, shepherds of their flocks, with their ovine-looking collars; the Lord High Chancellor, Alex Chalk, is high in physical stature and walked backwards with aplomb; the Duchess of Wellington was perfectly lovely in her tiara. And, near me, a new entrant, Lord (Andrew) Roberts of Belgravia, wrapped copiously in what he tells me were the oldest robes in the chamber, lent to him by Lord Willoughby de Broke, whose ancestor received his writ of summons in 1491, when Christopher Columbus was trying to raise money for a certain voyage west.

Then there is the Cap of Maintenance, famous for its obscurity. The Order of the Procession in which it is carried stated: ‘The Cap of Maintenance The Lord True.’ The Lord True is a real person, the much-admired present Leader of the Lords. I prefer to falsify history and claim that The Lord True was a permanent office under our old ways, like The Lord Steward, to distinguish him from the many Lords Untrue who beset all sovereigns.

One measure reiterated in the King’s Speech was the commitment to building a Holocaust memorial and learning centre in Victoria Tower Gardens next to parliament. This is one of those projects which governments promise in haste and repent at leisure but try, embarrassed, to stick with as opposition and costs mount. It bids fair to be the HS2 of memorialisation.

As the Covid Inquiry rakes over the coals of the fateful spring of 2020, Boris Johnson has been assailed for having taken a bit of time off to get on with his book about Shakespeare. He had a role model. Here is Bill Deakin, recalling an evening in the Admiralty in late March/early April 1940: ‘Naval signals awaited attention. Admirals tapped impatiently on the door of the First Lord’s room, while… talk inside ranged around the spreading shadows of the Norman invasion and the figure of Edward the Confessor, who, as Churchill wrote, “comes down to us, faint, misty, frail.” I can still see the map on the wall, with the dispositions of the British fleet off Norway, and hear the voice of the First Lord as he grasped with his usual insight the strategic position in 1066.’ Adolf Hitler may have been on the point of invading Norway, but Winston Churchill was late with his deadline for The History of the English-Speaking Peoples.

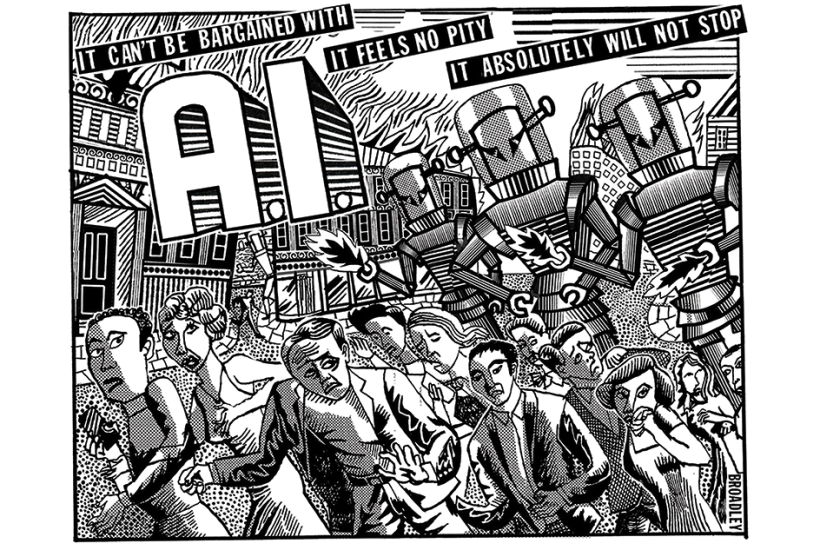

One of the many difficulties in thinking about AI is that I am sure the main figures in the story do not include themselves in the list of those who will have no work once it reigns supreme. Elon Musk obviously does not, and Rishi Sunak, who interviewed him last week at Bletchley Park, must feel fairly confident that a man of his modernity, non-artificial intelligence and Silicon Valley contacts will also find a place in the brave new world. Such men (about 90 per cent are men) probably feel quite perky; the rest of us, not. The trouble with intelligence is that it is not naturally humane. It tends be very bored by the slowness of others and rather self-admiring. One of the things I like about human beings is our intermittent stupidity. When I am wrestling with officialdom, a public service, a utility company, a local council, I am often buoyed up by the idea that those I am dealing with may be no more competent than I am and may therefore fail to overmaster me. It is a comforting thought. If Artificial Intelligence (AI) were truly as clever as it aspires to be, could it not create Artificial Stupidity (AS) as well?

It was typical of my trade that we covered our semi-exclusion from Bletchley Park as a major aspect of the story. ‘Journalists were at the event but were not allowed to ask questions,’ reported the BBC, as if this were lèse majesté. Of course we had to be restrained: otherwise we would have bombarded Mr Musk with questions about his treatment of X (the mania formerly known as Twitter) and ignored AI, which hardly any of us understand. The gathering reminded me of Mrs Thatcher’s Downing Street meeting of scientists and thinkers, such as James Lovelock, to discuss climate change with cabinet colleagues in April 1989. Obviously, most ministers thought it crazy and boring; obviously, the media were not there, and not interested. But actually, it turned out quite important in the history of how this subject captured the Western world.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in