Perhaps unfairly, Marcel Theroux does rather bring to mind Dannii Minogue. Not only does he look very similar to his more famous sibling, but when not writing (pretty good) novels, he’s in the same line of work: like Louis, he makes TV documentaries that feature much brow-furrowing.

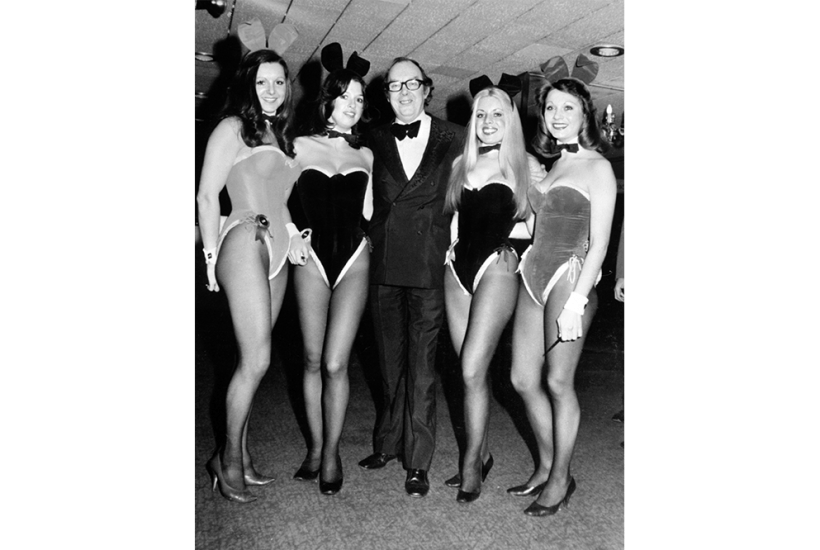

His latest was a neat fit for ITV1’s continuing obsession with true crime. As it transpired, The Playboy Bunny Murder was an over-simple title for an extremely tangled tale. Nonetheless, the programme did start with the killing of bunny girl Eve Stratford who, in March 1975, had her throat cut at her Leyton home. In those pre-DNA testing days, the police did what they could – which is to say they arrested and soon released Eve’s musician boyfriend, and then hoped for something to turn up.

‘I’ve never been able to regard paperbacks as real books’

For the next four years, not much did. But in 1979, Lynda Farrow – a croupier at another West End club – was murdered in her home in the same way. So, wondered Theroux, were the Met detectives right to believe these crimes were committed by the same man? As he would for much of both episodes, he investigated his own question with possibly excessive thoroughness before coming up with a firm ‘no’. And with that, he moved on to the testimony of Lynda’s mother: that her daughter had learned who Eve’s killer was and been silenced by an accomplice. Much assiduous sleuthing later, Theroux duly decided that she hadn’t.

But then came an especially baffling twist. Once DNA profiling entered the scene, a match was established between Eve’s murderer and that of 16-year-old Lynne Weedon in Hounslow in September 1975. This came even though the crimes were very different: Lynne was hit with a blunt instrument, raped and left for dead as she walked home from a night out – quite different to Eve’s murder in her home.

Theroux has apparently been examining these cases for years – and has the theatrical wall of press cuttings linked by red string to prove it. Nor could you fault his commitment as he tracked down crime-scene photos, coroner’s reports, Eve’s old boyfriend and what seemed to be every living detective involved in the investigations. Yet, perhaps for this reason, he appeared like a man who’d disappeared down a rabbit-hole with no obvious way out.

Instead, the theories continued to pile up – and then to be painstakingly discredited. The bottom of the barrel was reached with a careful consideration of the idea proposed by a former police intelligence officer: that Lynne had been killed by the Yorkshire Ripper on a trip to London.

The Playboy Bunny Murder did a fine – if somewhat alarming – job of conjuring up 1970s London. Theroux’s sorrow for the victims was obviously sincere. Even so, his regularly expressed wish that this documentary might help the truth to emerge one day began to sound increasingly desperate, as we were reminded all over again that messy old real life rarely offers the consoling satisfactions of fictional whodunits.

The Remarkable Journey of Bernard Levin took us back to the far-off days when influencers were clever men in specs who revered Shakespeare and said things like: ‘I strolled down to the water’s edge and thought about Wagner.’

The programme opened – as it more or less had to – with that trusty clip of Levin being punched on live television by the world’s poshest assailant. From there, it jumped about through the highlights of his career, reminding us that he wrote three Times columns a week for more than 30 years (an estimated total of 22 million words), and was also a TV star of some magnitude.

In his interview shows, he spoke to the likes of Robert Kennedy, Henry Kissinger and Stephen Sondheim. In his travel documentaries he showed there’s nothing new about middle-aged blokes in Panama hats joining in with such local activities as milking goats.

Along the way, we got a basic biography, which began surprisingly (to me at least) in the back streets of Camden, where Levin grew up as the child of a single mother whose own parents had fled the pogroms in Tsarist Russia. After scholarships to Christ’s Hospital and the London School of Economics, he cut his journalistic teeth by revolutionising the art of parliamentary sketch-writing in The Spectator. (‘As a schoolboy, I was astonished by how rude his column was,’ said Michael Billington, one of the many genial old hacks on display.)

But while the programme was touchingly celebratory in tone, it did acknowledge – I think deliberately – the edge of faint absurdity that came with Levin at his most lordly. In one travel scene he was reading Anna Karenina, ripping out each page after he’d read it and throwing it in the bin. This was partly, he explained, so that he’d have less to carry – but also because ‘I’ve never been able to regard paperbacks as real books’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in