In May 1966, Bob Dylan toured the UK with The Band, minus drummer Levon Helm, and abrasively pulled the plug on any lingering notions of his being a mere folk singer. Playing two sets every night – the first acoustic, the second electric – even the solo numbers were wild, lysergic, unravelled. The electric ones whipped through the tweed and tradition like the howl of a strange new language. The crowds booed and one chap famously cried ‘Judas!’ (though presumably many of those present also enjoyed it). Dylan muttered and swore and was unbowed. The fast-moving currents of pop culture changed course almost perceptibly.

In 1998, one widely bootlegged date from that tour was finally officially released as the fourth instalment of Dylan’s exhaustive and ongoing Bootleg Series of archival albums. Known as the ‘Royal Albert Hall’ concert due to an early and inaccurate claim on its provenance, it was actually recorded a week or so earlier, at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, on 17 May 1966.

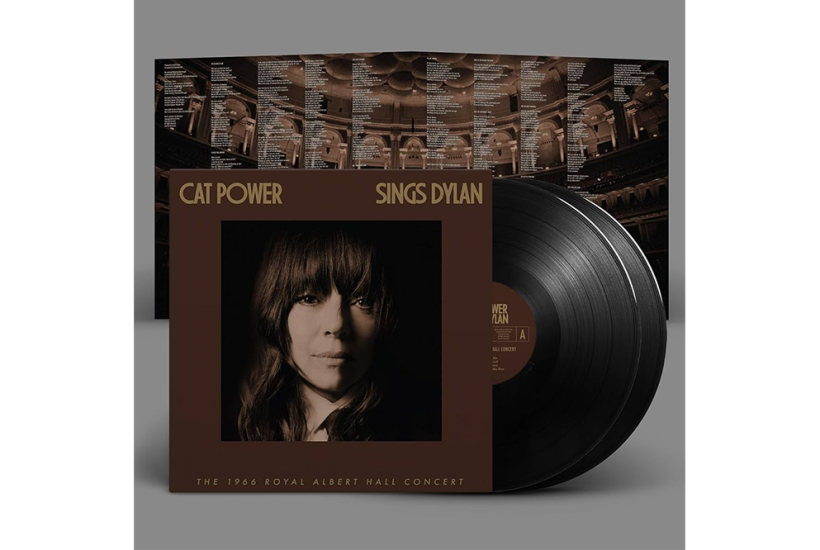

Last November, American singer Chan Marshall, who performs as Cat Power, recreated the entire Free Trade Hall concert – at the Royal Albert Hall. In other words, her aim was to engage with the mythology of the show as much as the music. A year later, that performance of a performance is being released as an album. Musical history is never linear. It folds layer upon layer.

What is the point of her doing this, you might reasonably ask. Well, there’s a couple of things. The first is that the original Dylan concert progresses like a terrifically compelling 90-minute play. It has its own internal drama, its own seesawing dynamic, and a climactic third act in explosive versions of ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ and ‘Like a Rolling Stone’. You might as well ask why anyone would bother staging Waiting for Godot after opening night.

The second point is that Marshall is a supreme interpreter. She has made her mark principally with three albums on which she has recorded other people’s songs, ranging from Mae West to the Pogues. Her voice is spare, sultry, twilit. She understands the power of restraint and emptiness. Give her the right lines and she will often as not do something extraordinary and unexpected with them.

Here, she has tamped down a natural inclination to play fast and loose, being more faithful to the ‘text’ than she might usually be. Dylan, and perhaps also the venue, tends to bring out an artist’s reverent streak. This album is on the one hand simply a souvenir of a historic recreation. The same songs played in the same order; even the same cry of ‘Judas!’ ringing out from the audience, this time to guffaws rather than uproar. ‘Jesus,’ Marshall responds.

But it is also an act of creative reimagination. Marshall possesses the same still, stoned, mesmeric quality in her presence as Dylan (sometimes) did at the time, but she also brings a deep devotional energy to the songs that wholly changes them. Her phrasing is as idiosyncratic as Dylan’s, only more nuanced. She has great musicians backing her – on acoustic guitar and harmonica in the first half, and a full electric band on the second half.

The acoustic set is slow and beautiful, a reminder of how deeply strange and yet brilliantly crafted songs such as ‘Desolation Row’ and ‘Visions of Johanna’ are. If this part feels as though Marshall is trying to tiptoe back inside venerated history, the second set is more raucous and good-hearted. It lacks any whiff of the rancour of the 1966 show, which means the original play is shorn of much of its contemporary drama. That piledriving rock’n’roll swirl – new and shocking at the time – long ago became the cultural default. Revolution becomes fond celebration. We all know these lines. Nevertheless, Marshall has done a fine job in making them sing anew.

The same can be said of Mickey Dolenz. On his new EP Dolenz Sings R.E.M. (one nice thing about both these records is that their titles tell you precisely what is on offer), the last Monkee standing has done rather wonderful things to four songs by the disbanded American group.

It’s an inspired fit. R.E.M.’s melancholic melodicism, rich harmonic sensibility and occasional bubble-gum tendencies owed an obvious debt to the Monkees. Here the circle of influence is completed with great joy, care and no little invention. The version of ‘Shiny Happy People’, in particular, feels as though it has brought the song home. In common with the three other tracks – ‘Radio Free Europe’, ‘Leaving New York’ and ‘Man on the Moon’ – it hits like a hefty dose of unfiltered sunshine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in