If the European Union created its own version of Mount Rushmore, who would it place in its pantheon? Horst Köhler, Helmut Kohl, and Francois Mitterrand – the architects of the Maastricht Treaty – perhaps? Or maybe Alcide De Gasperi, Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet, and Konrad Adenauer, who set in motion the long and winding process of European integration in the 1950s?

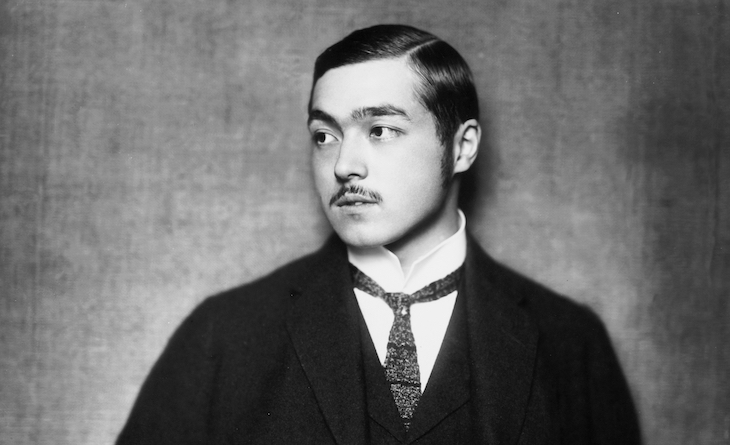

Almost certain to be overlooked is the man who founded the modern movement for European unity in the first place. That is, the eccentric, cosmopolitan Austro-Hungarian aristocrat Richard Nikolaus Eijiro, Count of Coundehove-Kalergi.

Kalergi had an unusual background. He was born in Tokyo in 1894 to an Austrian diplomat father and a Japanese mother. It was a rare match for the nineteenth century, one that required the personal permission of the Japanese emperor. Kalergi’s father had impeccably aristocratic credentials, which gave the family historic links to just about every corner of Europe, from Crete to Belgium. His son’s upbringing was decidedly ordinary by the standards of Austro-Hungarian aristocracy. Kalergi’s childhood was spent on the family estate in Bohemia where he was imbued with an aristocratic ethos and taught several languages, then on to schooling at the Theresianum in Vienna (the Habsburg Eton). After that his life took a strange turn. He went on to pursue a PhD in philosophy and married an older Jewish divorcee, which caused a minor scandal.

After the first world war saw the continent engulfed in violence, Kalergi founded the journal Paneuropa to advocate for European unity. For the next 14 years it would be the principal organ of his movement for the ‘Pan-European Union’. He became something of an international celebrity, schmoozing with the political, cultural, and social elites of the time and attempting to win them over to the dream of a united Europe. So great was his celebrity status that the dashing Victor Laszlo in Casablanca was based on him.

Part of Paneuropa’s lobbying activities included sending a questionnaire to prominent European figures asking them if they thought the creation of a United States of Europe was necessary and possible in the 1920s. The responses were printed in issues of Paneuropa, and were meant to show its subscribers how widespread the movement was. But as the responses make clear, despite the widespread philosophical support, it was difficult to imagine how such a union could be created in an era defined by anti-democratic mass movements and the rise of Nazi Germany.

Albert Einstein responded that a Pan-European Union was ‘absolutely’ necessary, but cryptically asked if it was possible. ‘Materially certainly. Psychologically?’ Or as the mayor of Cologne’s response, given pride of place in one issue, put it: It was necessary, but ‘not [possible] at this moment.’ That mayor was Konrad Adenauer, soon to be pushed out of politics by the Nazis and forced to live in seclusion for years before becoming post-war West Germany’s founding father.

Kalergi’s preferred strategy of attempting to convert national elites into a new pan-European ‘aristocracy of spirit and mind’ turned out to be a miserable failure in the face of nationalist and socialist movements that rather successfully mobilised the masses.

It is easy to see Kalergi as a figure caught in the past – a half-Japanese half-Bohemian-German aristocrat attempting to recreate the multinational Austro-Hungarian world of his youth on a continental scale. Or maybe was he simply ahead of his time – the first European to see the potential of today’s European Union.

The map of his envisioned Paneuropa is much closer to today’s map of the EU than the European Community of the Cold War or the early union of the 1990s. Notably, he excluded both Britain and Russia from consideration, thinking of both as too committed to their own empires and spheres of influences to participate in the European project. Fundamental to his vision of Europe’s future was the belief that the rise of non-European powers would relegate Europe to a global periphery. Only as a single continental bloc could Europe retain its sovereignty and role in global affairs.

Though somewhat light on details, he envisioned democratic and semi-democratic European governments coming together voluntarily to form a customs union and then eventually transforming into a United States of Europe modelled on the United States of America. Every state would have ‘maximum freedom’ within this federation and the legislature would be divided between a State House and People’s House, akin to the US Senate and House of Representatives. Curiously, he saw the introduction of English as a pan-European language taught in schools across the continent as crucial for the project because ‘the development of English as an international lingua franca is unstoppable.’

Relatedly, the second world war softened his attitude towards Britain somewhat, but it would mean little in the end. When it came to the eventual process of post-war European integration, Kalergi was shut out of the process, despite his close relations with Adenauer as well as Winston Churchill and Charles De Gaulle. Churchill even wrote the introduction to Kalergi’s autobiography, noting that the ‘form of his theme may be crude, erroneous and impracticable but the impulse and the inspiration are true.’ In a sense he was a victim of his own success. By the post-war years the ideals of European unity had become so widespread and thoroughly entrenched in the minds of western European elites that Kalergi was superfluous. Moreover, he had never and would never hold any actual position of power. He never stood in an election, so no European would ever vote for him. Who was he to dictate the terms of European unity?

In the end, Kalergi died in 1972 in relative obscurity. His grave in the Swiss Alps was neglected and forgotten until a Japanese admirer tidied it up and built a Japanese rock garden there several years ago. But the Pan-European Union did not end with him. His successor as its head was his close collaborator, Otto von Habsburg, the last crown prince of Austria-Hungary. Unlike Kalergi, he engaged with Europe’s new democratic politics. He spent two decades in the European Parliament, where he tirelessly advocated for the freedom of countries trapped behind the iron curtain. And, by extension, he advocated for Kalergi’s dream of a truly united Europe.

In 1989, Otto helped organise a ‘Pan-European picnic’ on the Austro-Hungarian border to test the resolve of the flagging communist regimes behind the iron curtain. Several hundred East Germans crossed the border unhindered, exposing the indolence of the regime. It was one event in a long chain that helped bring down the iron curtain. We can only imagine how Kalergi might have felt hearing that upon his successor’s death in 2011 the European Parliament held a minute of silence in his honour, and the head of its executive proclaimed ‘a great European has left us.’ Europe will probably never have a Mount Rushmore. But today’s European Union might just owe as much to Kalergi, Habsburg, and Paneuropa as it does to any of its post-war founders.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in