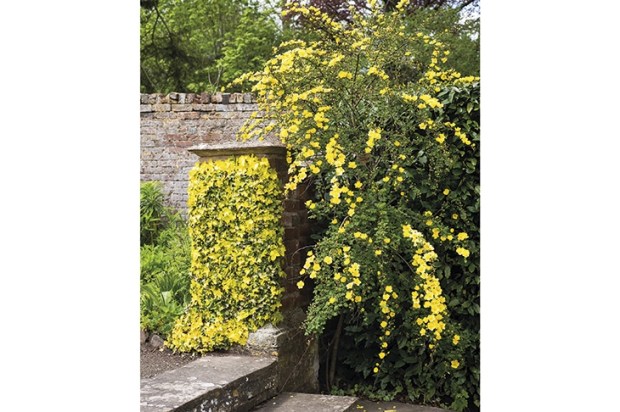

What makes a garden is an increasingly pressing question, in the light of what Jinny Blom, in her witty and wise What Makes a Garden: A Considered Approach to Garden Design (Frances Lincoln, £35), calls ‘hairshirt hubris’. By that she means the refusal of some gardeners to call any native plant a weed or any slug or aphid a pest. She wishes to inject a little sense into what has become an ill-tempered dialogue between ‘traditional gardeners’ and the self-deniers who cannot see gardens as anything but parcels of sacrosanct earth, in which any major intervention by a human is to be regretted. But to Blom, garden-making is one antidote to the modern curse of solipsism. ‘Gardens insist we care for them as much, or more, than ourselves.’

She started working life as a psychotherapist, and knows a great deal about the healing and regenerative properties of gardens. Twenty years ago, she turned to making gardens for a living and runs a well-regarded international design practice, based in London. This book is part memoir, part design manual, part exploration of the senses and part reflection on landscape and the designer’s art. Crucially, it is attractively presented and enhanced by sparkling prose. You could read it like a novel, if it were not in a coffee-table format; but the apt and beautiful illustrations and photographic images, with their wide cultural references, are integral, so you’ll just have to read it on your knee.

Unlike some garden designers, Blom loves plants and understands the dynamic of plant growth. I fancy she would get on well with the Pryors. Francis Pryor is the (now retired) archaeologist who discovered and excavated the internationally renowned Bronze Age settlement at Flag Fen on the industrial outskirts of Peterborough. With his equally distinguished archaeologist wife, he is also a fanatical gardener, as is plain from A Fenland Garden: Creating a Haven for People, Plants and Wildlife (Head of Zeus, £27.99). Accounts of how gardens are made and maintained rarely have universal appeal, unless the writing is exceptional or the author has some particular and unusual expertise. The writing here is workmanlike rather than sparkling, but the story it tells is fascinating.

The interest comes both from the unique perspective Pryor brings as an archaeologist, who knows and deeply respects the ground beneath his feet, and from the fact that, 30 years ago, the couple bought a 17-acre field in the Lincolnshire Fens, built a timber-framed house and barn, and made a complex garden, wildflower meadow, woodland and small sheep farm out of it. It was a hostile place, raked by north-easterlies channelled through the nearby Wash, and with soil devoid of worms or goodness, thanks to its previous incarnation as an intensively farmed arable field. But Pryor’s experience as a fenland archaeologist gave him familiarity with excavating equipment, drains, dykes and roddons, which proved invaluable. This is a charming story of a fruitful, resourceful partnership, which has produced a landscape of real quality, attractive both to wildlife and to visitors welcomed on charity open days.

Poets make fine garden writers – think of James Fenton, for instance – so I gladly picked up Led by the Nose: A Garden of Smells (Souvenir Press, £9.99) by the late Jenny Joseph. First published in 2002, the book is finally available in paperback. Scents, perfumes, smells – call them what you will – are the most difficult things to evoke, since we have so few words for them. As Joseph wrote: ‘What is less talked about becomes less noticed.’ But she knew well how much scent enhances our enjoyment of our gardens. This book would make a good present for a thoughtful, sensitive gardener, especially an elderly one who is tempted both to wear purple and to pick flowers in other people’s gardens.

Joseph referred to the flowers of an elder tree as having the smell of ‘a musty closed-in cupboard’. Don’t expect such flights of fancy from The Essential Tree Selection Guide: for climate resilience, carbon storage, species diversity and other ecosystem benefits by Henrik Sjöman and Arit Anderson (Filbert Press and RBG Kew, £50). Mercifully, a certain earnest clunkiness does not matter, since this is a reference book – and a very important one. The authors, a Swedish scientific curator at Gothenburg Botanic Gardens and a British garden designer and TV presenter, have interpreted – for the benefit of foresters, urban planners and gardeners alike – the latest scientific research on how trees function, as well as the power they have to do good (what the authors call ‘ecosystem services’). As they make clear, it is not enough simply to plant trees; you need to know which, where and how. The extensive A to Z tree directory, with characteristics and cultivation notes, is invaluable and the photographs are superb.

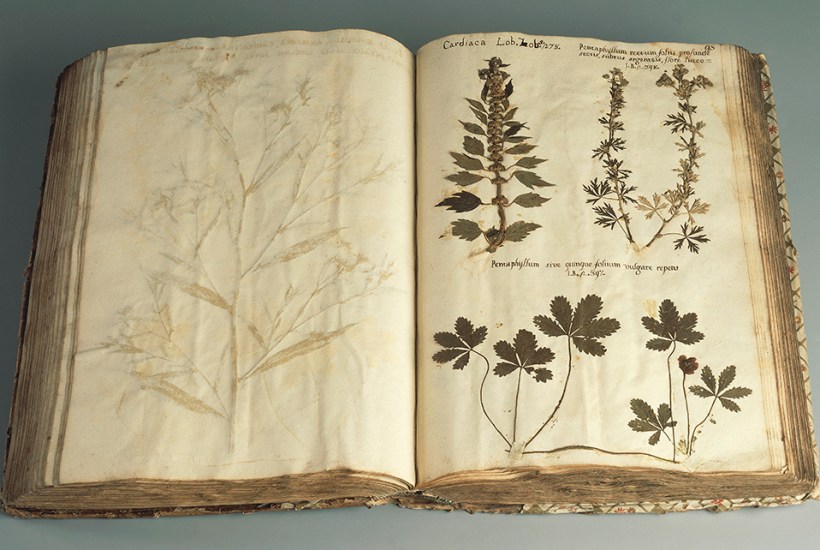

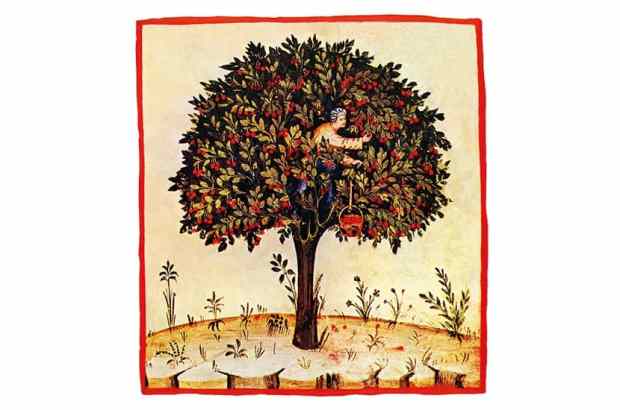

This book has the imprimatur of the Royal Botanic Gardens where, as in other botanic gardens across the world, dead plants play a vitally important role for botanical identification and exploration, as we learn in Maura C. Flannery’s scholarly but readable In the Herbarium: The Hidden World of Collecting and Preserving Plants (Yale, £25). Professor Flannery, an American biologist, became so beguiled by preserved plants that she travelled widely to herbaria, to study plants that have been collected, pressed, dried and preserved between layers of paper, then labelled and annotated, over nearly 500 years. The book is the fruit of her exploration into their vital importance for study (including now their DNA), but also what they tell us about history, culture, aesthetics and ethnobotany.

That importance has always been recognised. Napoleon even saw herbaria as spoils of war and stole them during military campaigns in Italy and Spain. Pressed specimens provide glimpses into a global plant-rich past, vital to help understand, and even inform the restoration of, biodiversity at a time of climate change and habitat destruction. As she says: ‘The plants are dead, but so much lively, passionate work went into creating the sheets and studying them, that they bristle with life.’

Pressed and growing plants are different sides of the same coin, which is why, since the first botanic garden was founded in Pisa in 1543, herbaria have been kept in large, well-ordered gardens. Botanists need both dead and alive for reference and teaching. This makes it all the more mystifying that the trustees at Kew have decided – to the dismay of botanists across the world – to relocate seven million pressed specimens, some safely preserved for more than three centuries, to a science park 40 miles away. I wonder if reading this compelling book might encourage them to change their minds.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in