The recent armed conflicts in Northern Kosovo and the reluctance of Serbia to recognise the existence of Kosovo as an independent state raise the question as to the importance of that territory for Serbia. To understand the current animosities, it is necessary to delve into the history of Serbia, specifically the region of Metohija.

Metohija is positioned at the south to southwest of Kosovo. It covers approximately 35 per cent of the total Kosovo area and has a population of over 700,000 people. It is the region where Serb people lived for thousands of years, where Serbia was founded, and where over forty Serbian monasteries are located, and Serbian culture flourished.

Serbia has a rich history. In 490 AD, a Serbian state was formed in the city of Skadar, which today is in Albania. Emperor Dušan proclaimed his Law Codex in 1349. Serbian territory gradually expanded south, north, and east from present-day Kosovo. In the 15th Century, the Ottoman Empire conquered the territory of Serbia, and some Orthodox Serbs opportunistically switched their allegiances from the Orthodox religion – the dominant religion following the division of the Christian Church into a Catholic and Orthodox denomination, which occurred in 1054 – to the Islamic religion to enjoy societal benefits. The 1455 ‘defter’ (Ottoman cadastral tax census) revealed that in the territory that is now Kosovo, there were only 46 ethnic Albanian families in 23 villages out of over 500 villages and towns where Serbs were in a majority. However, during the five centuries of Ottoman occupation, demographics changed significantly. Besides Serbs and Muslims, in the 19th and 20th Centuries, many Albanians immigrated north to Kosovo. These Albanians mostly adhered to the Muslim religion. During the second world war, approximately 200,000 Serbs relocated from Kosovo to central Serbia due to ethnic Albanian support for Nazi Germany. After the war, the Yugoslavian communist government, ruled by Josip Broz Tito, did not allow ethnic Serbs to return to their family homes in Kosovo.

Tito, who was an ethnic Slovenian surrounded himself with ethnic Slovenian and Croat staff and advisors. During Tito’s long tenure as the President of Yugoslavia from 1944 to 1980, Serbia, as one of the six Yugoslavian republics, was continuously weakened by partisan federal policy. During the 1950s and 1960s, Serb-owned factories were nationalised, dismantled, and moved to Slovenia. In 1974, constitutional reforms further weakened Serbia by creating autonomous regions, Vojvodina in the north and Kosovo in the south. Meanwhile, due to the hard-line regime of Enver Hoxha, leader of communist Albania, many Albanians illegally crossed the border into Kosovo and settled there without registering with the local government. They also failed to register their newborns and did not accept local government assistance. The immigrant Albanians lived in their own communities, spoke their own language, and established their own educational system. These Albanians came from the north-eastern part of Albania, the religion of which was mostly Muslim. Although these were undocumented immigrants, Serbia condoned their presence in Kosovo. However, in the early 1980s, Kosovo Albanians, although they were officially not Yugoslavian citizens, but buoyed by their increasing numbers and rapid population growth, demanded autonomy with the option of independence. Consequently, many international politicians made their careers by speaking on behalf of Kosovo Albanians and promoting their ideas. One such prominent politician was the American Senator Bob Dole, who travelled to Kosovo for the first time in 1990 – a turning point in Kosovo’s quest for independence.

And in 1999, following the bombing of Serbia’s capital, Belgrade, by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato), another 200,000 Serbs were forced to relocate to central Serbia. Nato’s action was in response to the Kosovo conflict of 1998-1999 when Serbian forces allegedly engaged in the ethnic cleansing of Albanians. These bombing raids destroyed multiple public buildings in Belgrade and killed civilians.

During the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Kosovo was the remaining obstacle that prevented the fragmentation of the Yugoslavian state. After the illegal Nato bombing of Serbia in 1999 – the UN Security Council never authorised the bombing raids, and a Human Rights Watch report concluded that Nato violated international humanitarian law – UN Resolution 1244 supported: ‘A political process towards the establishment’ of a political framework ‘providing for a substantial self-government for Kosovo, taking full account of … the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.’ However, nine years later, Kosovo declared independence and since then, together with the United States and the European Union, is lobbying for international recognition, the main objective of which is the acceptance and recognition by Serbia of the existence of the Republic of Kosovo as an independent state, eligible to be admitted as a member of the United Nations.

Ironically, what is happening today in Kosovo is that the government in Pristina – Kosovo’s capital – is seeking to rewrite history by declaring that Serb monasteries in Metohija are not Serbian but instead are Albanian. In this context, it should be noted that the earliest historical recordings on Albanians in Kosovo only date from the second half of the 19th Century. Furthermore, the small remaining number of Serbs that live in north Kosovo routinely experience hardships and suffer abuse from Kosovo authorities with the aim to limit the use of their ethnic language, culture, and way of life.

As Serbia has applied for European Union membership, the political pressure placed on Serbia to recognise Kosovo as an independent state is unrelenting. One reason for this is that recognition of Kosovo would effectively condone the illegal 1999 Nato bombing campaign and exonerate the culprits of this aggressive act towards a sovereign country, which resulted in the dismemberment of its territory.

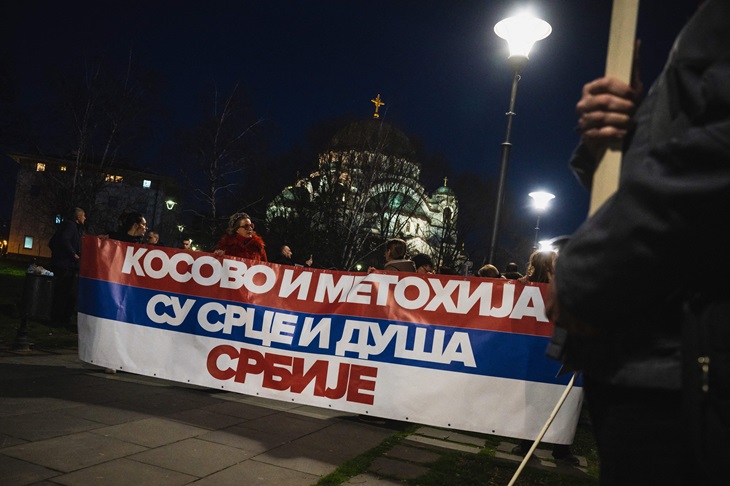

The local sentiment in Serbia is that Kosovo is part of Serbia, and that there are no legal grounds for its secession. Most Serbian people believe that Serbia should never recognise Kosovo independence. Moreover, Serbia’s population thinks that the international community, in evaluating Serbia’s application for membership of the European Union, is tricking the government in Belgrade into recognising Kosovo.

In conclusion, what Jerusalem is to Christians, Muslims, and Jews, Metohija is to Serbia. In other words, if it is legal and ethical to dismember a country’s own territory by creating an independent state, could this principle also be used in matters relating to Catalonia, Eastern Ukraine, Gaza, or perhaps even Hawaii?

Dejan Hinic is a financial and investment expert operating from Belgrade, Serbia. He received his law degrees from the University of Belgrade and the University of Queensland.

Gabriël Moens AM is emeritus professor of law at the University of Queensland and served as pro vice-chancellor and dean of law at Murdoch University. He is the co-author of The Foundations of the Australian Legal System: History, Theory and Practice (LexisNexis 2023). He has also published a novel about the origins of the COVID-19 virus, A Twisted Choice (Boolarong Press, 2020). His most recent co-authored book, The Unlucky Country will be published by Locke Press, Brisbane.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in