Everybody who knows nothing else about the French writer Renaud Camus knows that – as Wikipedia immediately asserts and as therefore is repeated every time he is mentioned in the press – he is ‘the inventor of the Great Replacement, a far-right conspiracy theory’.

Until now, actually reading Camus has not been possible in English, so thoroughly has he been shunned by the mainstream media. Here, at last, are some of his core political essays in translation, published by a small press in America, that will make such dishonesty blatant in future. It is in that way, for good or ill, an essential publication, as few can genuinely be said to be.

These are not the writings of Camus that I myself enjoy the most. I first became aware of him through a glancing reference in Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission in 2015. Intrigued, I bought a volume of his journals – he has published a fat book of them every year since the mid-1980s, also putting a new entry online for subscribers every day – and found myself captivated by his irascibility, his aestheticism and his radical honesty about being, in almost every little respect, about as deeply conservative as it is possible for a human being to be.

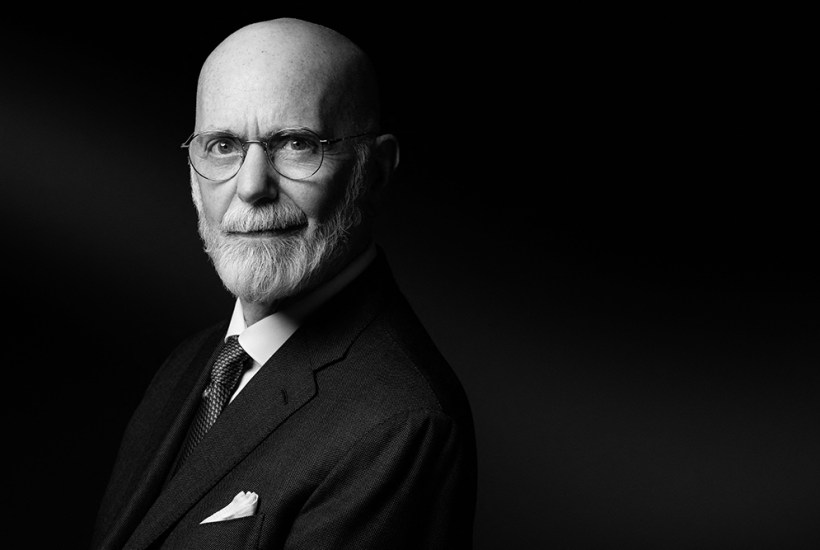

So in 2016 I went to interview Camus for Spectator Life, in the towering castle in the Gers he bought in 1992 by selling his small flat in Paris. I very much enjoyed meeting him and I’ve been reading his journals ever since.

The only book by Renaud Camus to have been translated into English previously was Tricks, of 1982, introduced by Roland Barthes, a journal explicitly describing 25-odd passing gay encounters. What has continued from that into all his subsequent work – unmanageable quantities of it, since he is a graphomane, his most recent tract La Dépossession running to 827 pages – is his commitment to such clarity, however awkward or unwelcome. As an addendum to his online journal he publishes on free access each day an ‘agenda’ of his life, detailing not only what he has read, written, seen, heard and eaten, but also his health, his finances and other setbacks.

Camus, now 77, told me that the notion of the Great Replacement occurred to him around 1996, when he was writing a survey of the department of the Hérault (he has written many excellent guidebooks under the rubric Demeures de l’Esprit, including two on Britain). In the medieval villages there, he found, as he says here in a speech delivered in 2010 simply titled ‘The Great Replacement’:

There almost exclusively appeared a population never before seen in these parts, which by its dress, demeanour and even language seemed not to belong there but rather to another people, another culture, another history.

Some may welcome such new arrivals, but Camus considers the change of population to be an unprecedented disaster:

In 15 centuries, there has not been a single episode, dramatic though some may have been, neither the Hundred Years War nor the German occupation, that has represented a threat as serious, deadly and virtually definitive in its consequences for our homeland as the change of people.

He does not accept that these incomers can be French in any true meaning of the word: ‘If they are just as French as I am then French does not mean much.’ He uses the image of Lichtenberg’s knife – ‘one changes the haft, then the blade, but it is still the same knife’ – to illustrate what is happening.

Camus does not cite any population statistics, those relating to ethnicity in any case being forbidden in France. But, he urges, ‘it is not yet entirely forbidden to believe one’s own eyes and one’s own daily experiences’. One statistic worth knowing, however, is that, despite having been cancelled by his publishers, Fayard and P.O.L, since 2010, resorting to self-publishing, and being prosecuted and traduced, this term that Camus invented has become very widely used in France and not only among followers of the National Rally or Éric Zemmour. A poll from 2021 by Harris Interactive revealed that 61 per cent of respondents thought the Great Replacement would happen.

The other pieces translated in this obliquely titled collection all revolve around the central idea. Camus believes that only educational collapse – ‘the little replacement’ – could have allowed the change in population to happen as it has, having faith that a people that knows its classics does not consent to its own disappearance. The Great Deculturation is a fierce defence of cultural elitism against what he calls hyperdemocracy, ‘the implementation of equality in domains where it has no business’.

In ‘The Second Career of Adolf Hitler’, he contends that it is the legacy of Hitler that has effectively prohibited

not only all references to races, it goes without saying, but also to one degree or another all reference to ethnicities, peoples, civilisations, diverse cultures, origins in general, and nations in their temporal aspect, that is, their heritage, transmission and survival.

Throughout, Camus emphasises that he does not believe in a conspiracy:

Alas, no, what I believe is that there are obscure movements in the depths of the species, subject to the very laws of tragedy, starting with the first of them, which has it that the wishes of men and civilisations whose disappearance is foreordained shall be granted.

The ‘Great Replacement’ is simply an observation, offensively named.

So there they are, in English now, these statements, saying the unsayable with eloquence and vim. The translators are at pains to say that they wouldn’t have published the book if they had thought it would lead to Camus’s inventive terms being further turned to evil ends ‘by determined, violent racists and white supremacists whose violence Camus abhors’. Indeed, they claim, they’re actually making that less likely by filling in the ‘contextual vacuum’.

They make little mention of Camus’s other works, his novels, elegies and eclogues, those remarkable journals and his prolific, aphoristic tweets. There the reader realises that his conservative horror of change extends much further: to the casual use of first names, to degenerate syntax, to the appearance of wind turbines, the prevalence of pop music, the general suburbanisation of the world, T-shirts, public transport, the use of mobile phones in public, loud voices, the disappearance of double doors in hotels. He craves silence, space, courtesy and kindness.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in