One of the reasons so many Australians voted No in the landslide rejecting the Voice was that, as the official No case stated, ‘The High Court would ultimately determine its powers. Legal experts don’t agree, and can’t know for sure, how the High Court will interpret such a constitutional change.’

There is, at best, a wariness about the High Court.

But such confidence that remains in the court as a national institution will plummet as people become aware of the recent successful actions brought by a convicted terrorist and a convicted child-sex abuser, the subject of final decisions by six or fewer unelected black-robed lawyers

As to the cases the Court chooses to consider on appeal from lower courts, the High Court usually performs properly, as it did in the appeal brought by Cardinal Pell. There it applied unanimously the elementary principle, curiously overlooked by the Victorian courts, that a crime must be proven beyond reasonable doubt.

The fact is Australia never had to have a High Court which goes beyond hearing appeals and is empowered to invalidate legislation.

At Federation, neither the UK nor Switzerland did.

And given the disastrous history of the US Supreme Court, especially in relation to the Civil War and later segregation, it is surprising our founders were not wary about creating a similar court here.

In fact, the Australian constitution leaves it to parliament to confer the power of interpretation on the High Court.

But if it had not, the Court would probably have done what the US Supreme Court did in the celebrated case of Marbury v. Maddison (1803) – confer the power on itself.

In any event, we have a High Court that can invalidate legislation. Its decision is final.

That is, final until a future High Court changes its mind. That has just happened, and spectacularly so.

This related to its 2004 decision that the fact that a non-citizen faces indefinite detention does not mean that the provision authorising this is unconstitutional. Now it is unusual, but not unknown, for the High Court to overrule a precedent. The High Court has now heard the appeal by a Rohingya man from Myanmar, known as ‘NZYQ’. He was in detention, after serving time for raping a 10-year-old boy. Normally he would be deported. The government accepts that he is a refugee and therefore unable to be sent back to Myanmar. Unsurprisingly, no other country will take him. He therefore faced indefinite detention.

The Chief Justice recently and somewhat inscrutably announced that ‘by at least a majority’, the judges had agreed that the provision was unconstitutional. The court, he said, would publish reasons ‘in due course’. There was, of course, an order for costs.

We know neither which judges supported this, nor their reasons. And why was the Court in such a hurry to have NZYQ released?

This reminded me of the 2010 Get-Up case.

There the High Court bent over backwards to hurriedly hear two plaintiffs, both in breach of the electoral law. In a rushed decision announced on 6 August, the Court held the 2006 amendments to the Commonwealth Electoral Act closing the one-week window between the calling of the election and the closing of the rolls was unconstitutional.

Close to 100,000 additional voters, impossible for the AEC to verify, were then put on the rolls. The 21 August election resulted in a hung parliament. Hardly anyone noticed when the court published its reasons and revealed it was a close 4:3 decision just before Christmas.

The reasons are, in my view, unpersuasive.

Returning to the current cases, the release of NZYQ and it is thought, over 90 others, followed another successful appeal, this time by a notorious terrorist, Algerian Abdul Nacer Benbrika. He was found guilty in 2008 of leading a terror cell that plotted attacks on Melbourne landmarks in 2005, including the AFL grand final. By a 6:1 decision, the Court ruled that the legislation under which Minister Peter Dutton stripped him of his citizenship was unconstitutional. Because of the separation of powers, this, they said, could only be done by a court. This should not have come as a surprise to the legislators as the judges were clearly heading this way.

One solution might be to have a federal terrorist offence which carries a mandatory punishment including the removal of Australian citizenship from dual citizens.

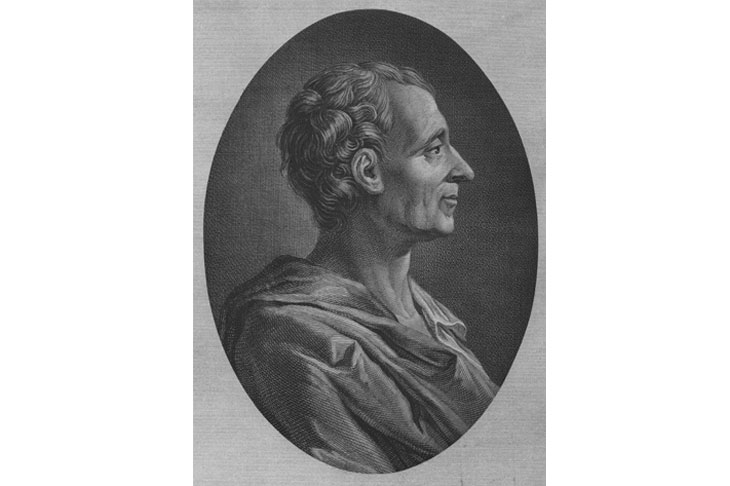

Montesquieu saw the separation of powers, which he found in England, as a way of controlling the abuse of power. In practice, the separation has never been precise. There are several exceptions, above all the intermingling of the executive and legislative powers in the Westminster system. While a general ministerial power to strip citizens of their citizenship would not be acceptable, attaching it to a serious criminal conviction with appropriate safeguards should, on reflection, be in order.

What is undoubtedly unacceptable to rank-and-file Australians is to see plaintiffs like these profiting from long and expensive trials, talk of civil claims for damages, the release of others including a murderer, and that the decision of a few judges is final. The judges might as well say the constitution means whatever they say it means.

The founders who were well informed could have guarded against this.

Patrick Glynn, who proposed the most approved part of the constitutional system, the reference in the preamble to the blessing of Almighty God, proposed the court consist of a chief justice and all state chief justices. That would have removed its centralist trend that has moved so much power to Canberra and avoided the failure of politicians on both sides to appoint judges who will strongly defend the federation and interpret the constitution as it was originally intended.

What is needed now is to ensure that, as in Switzerland, the Australian people are equipped to review and overrule the court, not on specific decisions, but on constitutional interpretation.

On that, until next time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in