More people are being jailed than the justice system can manage. There are only 557 places left across 120 prisons in England and Wales, while prisoner numbers are increasing by 100 to 200 every week. Justice Secretary Alex Chalk had some tough-sounding rhetoric on Monday to deal with the problem: lock up dangerous offenders and send foreign criminals back home. Yet it distracted – perhaps deliberately – from the most liberal penal policy reform announced by a government minister in decades: a legal ‘presumption’ against short sentences.

Does the government want the message to go out that shoplifters won’t hear the clang of the prison gates?

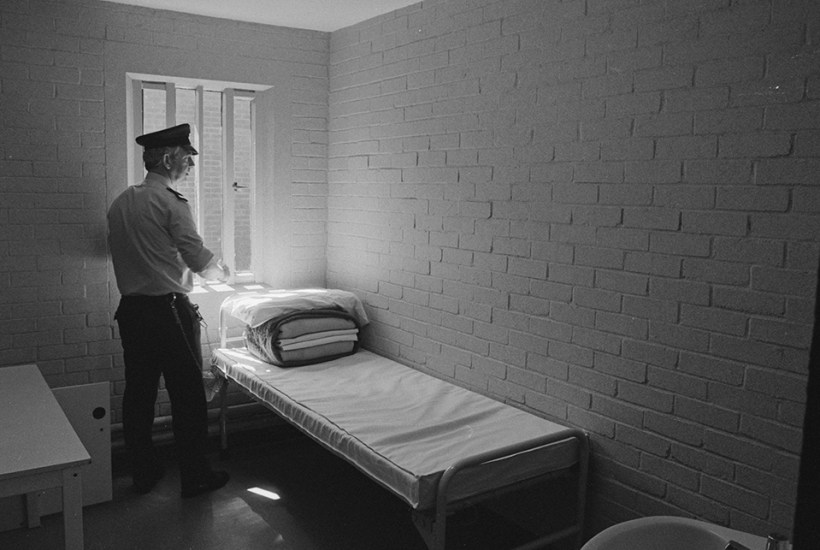

Incarceration is expensive: it costs £47,000 per inmate per year. In many cases, the costs are hardly important compared with the need for public protection, punishment, deterrence and rehabilitation. Yet for offenders given short jail terms, a growing body of research suggests prison simply makes things worse and is not cost-effective.

Short sentences sever prisoners’ family ties, disrupt employment and provide little time to address offending behaviour, poor mental health or addiction problems. As the former prisons minister Rory Stewart put it, these terms are ‘long enough to damage you and not long enough to heal you’. Reoffending rates are appalling. More than 50 per cent of adults who are sentenced to less than 12 months in custody are convicted or cautioned within a year of release. For those who are jailed for up to six months, the figure is approaching 60 per cent.

Criminal justice campaign groups have argued for many years that short prison terms are useless. Community sentences would be a better and a far cheaper option, they claim. Their calls were ignored by both parties, who were worried about appearing ‘soft’ on crime. But in 2019, then justice secretary David Gauke, encouraged by Stewart, secured backing from No. 10 for a change. Gauke had commissioned a study that found that offenders given a community order or suspended prison sentence were 4 percentage points less likely to reoffend than those jailed for less than 12 months. In a speech in July of that year, he announced plans for restrictions on the use of short prison sentences, saying it would lead to ‘thousands’ fewer victims of crime. Four days later, however, when Boris Johnson was confirmed as Theresa May’s replacement as prime minister, Gauke resigned. His departure, and Johnson’s premiership, stopped the reforms.

It was a missed opportunity. Since then, the prison population has grown by almost 6,000 to 88,225 – the highest it has ever been. We’ll never know for sure, but it’s possible that if Gauke’s plans had been implemented the capacity crisis now facing our prisons would have been averted.

Chalk revived Gauke’s ideas on Monday, saying that the government would legislate to ensure the courts move towards suspending prison terms of less than 12 months rather than sending criminals directly to jail. Exactly what that means in practice depends on the wording of the legislation and how the courts interpret it. Chalk has already said short prison terms will still be an option for prolific offenders, those who breach the terms of court orders and criminals who ‘blight’ communities. Nevertheless, with jail sentences of less than 12 months making up 55 per cent of all custodial penalties, it has the potential to make a sizeable dent in the prison population, reducing the number at any one time by up to 3,000 – the equivalent of two large jails.

This approach has to strike a balance. If the rules are tightly defined and rigorously adopted by the courts, they risk creating a two-tier justice system: on the one hand, the most serious crimes will result in long spells behind bars while, on the other, a whole class of offending will seldom, if ever, lead to a prison sentence. At present, one in every eight sentences of less than 12 months is for shop theft. There is already huge concern about whether shoplifting is effectively legal. Does the government want the message to go out that shoplifters won’t hear the clang of the prison gates? There’s also the problem of violent offences, including common assault and attacks on emergency workers, which make up one in six short sentences. Will those responsible really have their sentences suspended under the new regime? At the same time, if ministers create too many exemptions, the changes will be pointless, and prisons will only get more crowded.

Alex Chalk has made a bold move to halt the soaring prison population, and all things considered, this policy should help things. But the judiciary must still be able to impose short prison sentences on those whose behaviour has not been changed by other punishments – and where public confidence demands it. Fewer people in prison is a good thing, but the public will want to know which people and which crimes don’t deserve jail.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in