A little more than a week before Hamas carried out its Operation Al-Aqsa Flood, the US National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, said: ‘The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades.’ Sullivan was expressing a consensus view, one apparently shared by the Israeli government. Then came the attacks of last weekend and, as the Israeli President, Isaac Herzog, said, ‘Not since the Holocaust have so many Jews been killed in one day.’ The surprise attacks have been called Israel’s 9/11, its Pearl Harbor, and so the question Israelis are asking is: how could this happen? And of more consequence, perhaps: who was really behind it?

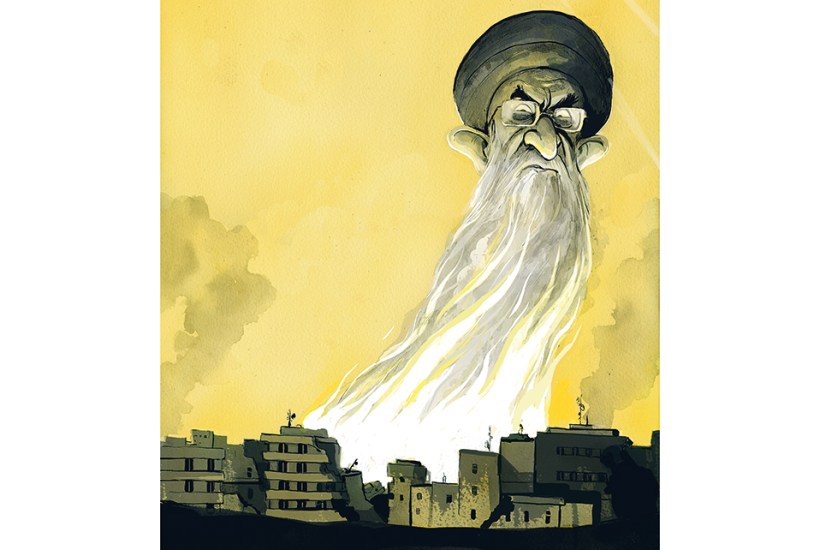

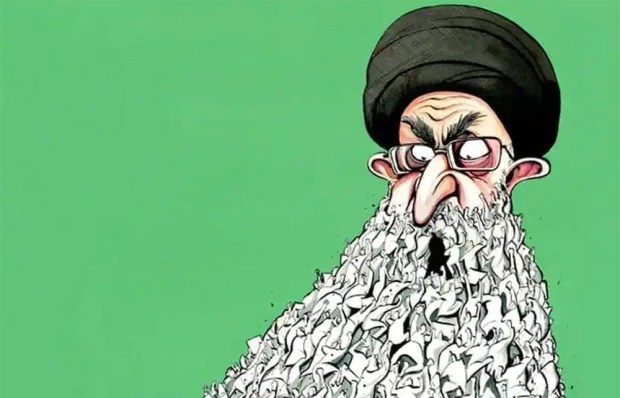

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Kha-menei, denies it was him. In a televised speech he said: ‘We kiss the foreheads and arms of the resourceful and intelligent designers [of the operation]… but those who say that the recent great event is the work of non-Palestinians are making miscalculations.’ Khamenei delivered his speech wearing a Palestinian scarf. There followed some standard rhetoric about ‘the Zionist regime’s’ ultimate defeat. ‘I say that this devastating earthquake has managed to destroy some of the main structures of the oppressive regime’s rule, the reconstruction of which is not easily achievable.’

What happened in Israel is certainly being celebrated in Iran’s official media – a cartoon in a government-run newspaper shows a Palestinian boy making the victory sign with his fingers and holding two balloons that read ‘1k’, a reference to the death of more than 1,000 Israelis. The caption reads: ‘We reached a thousand.’ But the US government says its intelligence agencies have yet to find proof that Iran planned these attacks. Still, Joel Rayburn, who used to be in charge of Iran policy on the US National Security Council, isn’t buying the denials. Iran was the author of the attacks, he told me. Hamas was not an independent actor.

He said that Iran’s Quds force, which runs Tehran’s foreign military -alliances, has continually tightened the reins of control with its proxies and clients such as Hamas. They would have directed any major initiative, including its timing and execution. ‘That’s the way their relationships operate. And there’s no exception.’ It’s been widely suggested that Iran was trying to stop Israel signing a peace treaty with Saudi Arabia.

Rayburn believes it’s more nuanced than that. He told me that Iran had been trying to build up Hamas to be more like Hezbollah, the force it commands in Lebanon. The US says Iran sends Hamas $100 million a year but more importantly has instructed Hamas engineers in how to make rockets from common materials such as pipes and fertiliser. Rayburn said Iran wanted to be able to threaten Israel in the south with Hamas and in the north with Hezbollah, ‘to paralyse Israel and by extension to paralyse the United States’. In the absence of a nuclear weapon, he said, Iran needed Hezbollah and its missiles for deterrence, so ‘preserving Hezbollah is a strategic imperative’.

Rayburn said that if Hamas were destroyed in Gaza, as Israel intended, that would leave Hezbollah dangerously isolated. ‘That is something that the Iranian regime and Hezbollah cannot tolerate.’ In other words, the war will spread – into Lebanon, and perhaps Syria, Iran and the wider Middle East too.

I spoke by phone to a senior Hamas politician, Osama Hamdan, about the alleged Iran connection. He used to be the Hamas representative to Tehran and, coincidentally, was photographed there – standing next to the Supreme Leader– the week before the Hamas operation. He stuck to what seems to be the agreed line, denying that Iran was behind the attacks. Iran supported Hamas just as the US supported Israel, he said. It did not dictate. Echoing Khamenei’s words, he added: ‘All that has been done is our will, from the Palestinians.’

Hamdan called what happened at the weekend ‘a legitimate operation against the Israeli army’, adding that videos on social media showed ‘huge moral actions’ by Hamas fighters: one had told a frightened female hostage and her two children that ‘We are Muslims, we will not harm you’; another had asked permission before taking food from an Israeli house. What about the videos showing the summary executions of civilians? ‘Every-one is talking about the blue blood of the Israelis. But no one is talking about the red blood of the Palestinians. This is hypocrisy.’ He went on: ‘You can’t control everything, everywhere; you can’t control everyone. I’m sorry for what may have happened. But the fact is, our people are being killed. That was happening because of what the Israelis have done. It was a normal reaction.’

The part about not being able to control everyone revealed something important about the bloodshed at the weekend. Hamdan told me that all of Gaza’s militant groups had taken part in the attacks. In fact, a number of civilians from Gaza seem to have joined in as well, pouring through the fence once it became clear that the Israeli military wasn’t coming, a do-it-yourself pogrom. The men on the quad bike kidnapping the concert–goers were not wearing uniforms, for instance. As one Palestinian academic put it to me, the sheer scale of the Hamas attack may not have been planned. Things got out of control. They might not have planned for the reaction, either. I asked Hamdan if Hamas had, in effect, committed suicide by organising such attacks. No, he said – Israeli governments had promised many times in the past to end Hamas but they had always failed. ‘They will not break the resistance.’

What then was the strategy? What were the attacks supposed to achieve? To end the occupation, Hamdan said. There was ‘no need for anyone to be killed’ if Israel did that. He meant the occupation by Israel of land captured in 1967: the West Bank and east Jerusalem. Despite Hamas’s founding charter calling for the destruction of Israel, since 2017 the group’s stated position has been for a settlement based on the ’67 borders.

Hamas had been forced to order its attack, he said: under Netanyahu’s government there was no hope for a Palestinian state; more settlements were being built, more land stolen, the West Bank was being steadily annexed. ‘This means the end of the Palestinian cause. The Palestinians have to act. The Palestinians have to defend themselves. This action [at the weekend] is to tell everyone: there is a Palestinian nation, and they are still resisting the occupation. And they are seeking to have their freedom and to build their independent sovereign state on their homeland.’

I spoke about all this with Danny Yatom, a former head of Israel’s spy agency, Mossad – starting with the attacks on Israel. This is a man whose profession had been to anticipate the worst, to think the unthinkable, but he said over and over how ‘shocked’ he was. This was not, however, so much a failure of intelligence as a failure to correctly interpret intelligence and to act on it. There were clear signs that Hamas was planning something. In full view of Israeli drones, they carried out an exercise to attack a mock Israeli settlement they’d built in Gaza. The Israeli army even reported that Hamas forces were gathering near the border fence. But the analysis was that Hamas wanted quiet, not least so that it would get cash from Qatar. So the intelligence chiefs – and the politicians – ignored the evidence. ‘They did not read correctly the intentions of Hamas.’

According to Yatom, the attacks also happened because Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, had acted deliberately to build up Hamas so as to weaken the Palestine Liberation Organisation, which rules in the West Bank. Sounding at times almost like Hamdan, Yatom said that Netanyahu wanted to make sure there would never be a Palestinian state, to stop any possibility of negotiations, to annex ‘Judea and Samaria’, as Israelis call the land west of the river Jordan. So Netanyahu allowed money for Hamas to be sent to Gaza and he allowed supplies – especially cement – for aid projects that ‘everyone knew’ was going to build the infrastructure of Hamas. ‘He wanted to buy silence along the Gaza border… He wanted to buy silence from Hamas.’

The result was a day of chaos and confusion more horrific than any that Yatom had seen in his decades as an intelligence chief and as a soldier – he retired as a major general – and that included the Yom Kippur war. All this could wait for a public inquiry but for now the effort should be to ‘harm Hamas very badly… They slaughtered hundreds of innocent Israelis: women, children, the elderly, babies. No one will be able to forgive these terrorists. It should be painful. It should be severe. So Hamas will not be able to rehabilitate for many, many, many years to come. Every option is on the table.’

In Jerusalem, the godfather of Israeli strategy, Professor Martin van Creveld, was gloomy about a second front in the north and about the prospect of ever attaining peace based on the two-state solution. The 500,000 Israeli settlers now in the West Bank made that impossible. ‘Twenty years ago, I very much hoped it would happen, but it’s too late for that. It will never happen. Never. Never.’ With members of his own family mobilised, he agreed that Israel seemed doomed never to see the end of war. That did not mean the fighting in Gaza would continue indefinitely. Israel would eliminate Hamas’s weapons and then negotiate a ceasefire with them. ‘We’ve been negotiating with Hamas for 20 years and anyone who says otherwise doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’

For all the justified talk of a new and unprecedented phase in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, this may be the most likely outcome. If there is to be an earthquake, as Khamenei says, it may shatter the wider Middle East yet leave the conflict at the heart of the region relatively untouched.

In the past, stung by some suicide bombing or other outrage, Israelis have spoken of ‘mowing the grass in Gaza’ – a terrible phrase given the reality of modern weapons. That is what is happening now, albeit on a larger scale, over a longer period, with more blood spilled. To adapt Winston Churchill’s famous phrase about the Ulster conflict, once the smoke of battles recedes, the same landscape will emerge – the red roofs of the settlers, and the minarets of Hamas – ‘the integrity of their quarrel’ unaltered, however devastating the surrounding cataclysm.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in