To present a TV history documentary these days, one must first have access to the full Angels and Bermans dressing-up box – everything from britches to bonnets. The past must be experienced as pantalooned immersion: throw in some CGI cavalry charges or naval battles, plus artfully dressed period locations, back-alley washing-lines fluttering with greying rags, and you are just about ready to go. This is not necessarily to complain. Every generation finds its own way of exploring complex historical questions.

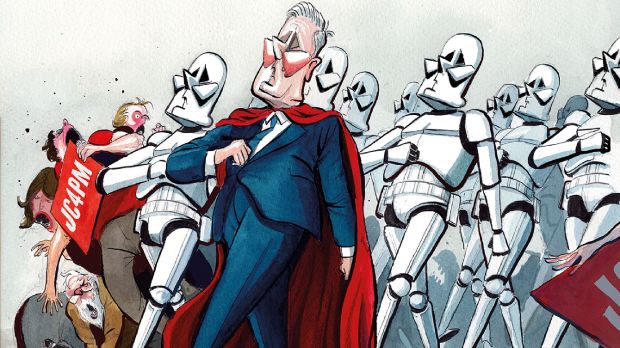

But there is one television series that stands as a monument to the virtues of focused seriousness, and that is still being streamed today. Fifty years ago this month, in 1973, ITV audiences sat down to watch – and to absorb – the most remarkably comprehensive and compelling chronicle of the then recent past, The World At War. It went out on Wednesdays at 9 p.m. for 26 weeks, and its aim was panoptical: examining not just the decisive military developments, but also the crushing human impact of conflict, as experienced from London’s East End to Japan.

The conception of the producer Jeremy Isaacs (later the first, pioneering head of Channel 4), it was commissioned by Thames Television and – thanks to an extraordinarily high budget for a documentary series – was filled with the most dazzling research and careful nuance.

It mixed extraordinary contemporary footage from all theatres of conflict with some remarkable and occasionally startling interviews: from the bomb-happy US general Curtis LeMay and Hitler’s secretary Traudl Junge to the former prime minister Anthony Eden; from civilian survivors of the Siege of Leningrad to the pilot of the Enola Gay and gently boozy East End Blitz veterans. In the case of the episode dealing with the Holocaust – a subject which at that stage was still not widely discussed on television or elsewhere, as if the world was still flinching – the quiet interviews were devastating.

The series overall was produced with the help of the Imperial War Museum. The plangent title music by Carl Davis, and the accompanying images of photographic faces melting in flames, remain haunting. The episodes were threaded through with scripts of great elegance and careful structure, narrated with distinction by Sir Laurence Olivier.

‘After he did the first episode, we had a message through that Olivier wasn’t going to do any more,’ says one of the directors and scriptwriters, David Elstein (who himself went on to forge the most remarkable broadcasting career). What had gone wrong? ‘Olivier’s agent suggested he didn’t feel loved enough,’ says Elstein. ‘Jeremy Isaacs had to go and see him to tell him how marvellous he was.’ Mollified, Olivier thereafter narrated the remaining 25 episodes.

Elstein himself secured some of the series’ most remarkable moments. In an interview with the Luftwaffe general Adolf Galland, it emerged that unlike their RAF counterparts, the German fighters saw no special significance in the Battle of Britain, except as a dummy run for an attack on Russia. US bomber supremo Curtis LeMay suggested that in terms of the war with Japan, the US simply ran out of cities to burn; even the nightmare 1945 attack on Tokyo, in which some 100,000 perished in the all-consuming fire, did not appear to bring the end of the war much closer. And so, as LeMay elliptically hinted, the atomic bomb was all that was left. The series, says Elstein, ‘overturned assumptions’.

But, says Elstein too, what also made the series remarkable was the weight given to other interviewees in all walks of life. Previous documentaries had featured ‘generals in sandpits pointing at tanks’. The World At War was careful to follow the repercussive effects on wider populations, and of what happened after the conflict as well.

Another extraordinary aspect of the series in today’s terms is the fact that even the most famous interviewees were not given special treatment, but were intermixed with less famous voices. This led to double-takes: the sudden, unannounced appearance on screen of Albert Speer, the Nazi minister for armaments – himself not long released from his war crime sentence in Spandau prison – is at first startling, and then grimly fascinating; the persistence of his vanity combined with his continually veiled soul. This interview has itself become a fragment of history.

‘It was demythologising but not iconoclastic,’ says Elstein of the series’ broader approach. Authenticity was absolutely key. An adviser saved the team when he told them that Soviet footage of the 1943 Battleof Kursk was fake – he could tell by the angle of the sun. The battle had in fact been re-staged for Soviet cameras after the Nazi retreat. Conversely, in terms of popular myth, London interviewees were happy to divulge that when Winston Churchill visited the bomb-damaged East End, he was booed by some. His private secretary Jock Colville disclosed for the first time that Churchill’s ascension to office in 1940 had been met in some government circles ‘with despair’.

Isaacs gave his writers and directors free rein. One such writer, the brilliant Neal Ascherson (whose episode on Operation Barbarossa is utterly hypnotic) might, Elstein suggests, now aver that the series was missing an episode on many of the wider horrors within eastern Europe, the ‘bloodlands’. ‘We didn’t give enough weight to it,’ says Elstein. ‘But there wasn’t the footage.’

But Ascherson, Elstein and the other writers found a unique blend of eloquence and economy, all enhanced by Olivier’s nuanced narration (even if some of his pronunciations were eccentric – he had to be dissuaded from referring to Soviet leader ‘Staleeeen’, and these days his sharp delivery of ‘The Ukryne’ is also arresting). Elstein, himself a historian, learned this particular craft on an earlier series, Day Before Yesterday, where the presenter/narrator Robert Kee told him that his first draft script had ‘far too many words’ and that he ought to ‘let the pictures breathe’, to ‘let people absorb the images’ and to ‘sculpt his script’.

Unlike many of today’s history programmes – where the grammar of television demands that they continually clamour for the viewer’s attention, with noisy intros, art-house shots of presenters staring into the middle distance, and continual simpleton summaries of all that has been said so far – the directors of The World At War were working on the assumption that their audiences were intelligent and receptive. ‘In the days before video recorders, we did think that if someone sat down to watch an episode, then they would be sitting there to watch the whole thing,’ says Elstein. The ratings were more than respectable too.

Ironically, nothing dates faster than history. Yet The World At War retains a freshness and a capacity for surprise, as well as featuring so much amazing footage that hasn’t very often been seen since. Partly because the series was spread out over 26 weeks, there was more room for rare images of, for instance, 1930s Berlin (the macabrely paganistic Nazi torch-lit funeral of President Hindenburg), or white snow-suited Red Army troops vs literally freezing under-prepared Wehrmacht forces.

The team did not anticipate the extraordinary afterlife of the series (though it was a huge critical success in both the UK and America). It has been replayed frequently. Yet David Elstein is slightly frustrated by the show’s current streaming incarnation on UKTV Play. In fairness, the service is free and all 26 episodes are there. But they are peppered with advertisements and each is abridged to 44 minutes (rather than 52). What would be ideal, he says, is if BBC4 – a channel in part dedicated to history – might see its way to a discussion with the rights-holders Fremantle to mark the 50th anniversary by hosting a proper re-run of all the full-length episodes. The series, after all, counts as a -valuable artefact in its own right.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in