A year ago Liz Truss’ brief government collapsed when markets lost confidence in Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget. A large part of the problem, it was explained at the time, was that the Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) – founded by George Osborne specifically to provide some independent backing for Budget measures – had not been invited to give its views.

Isn’t the real problem that the OBR fails to make any allowance for political events?

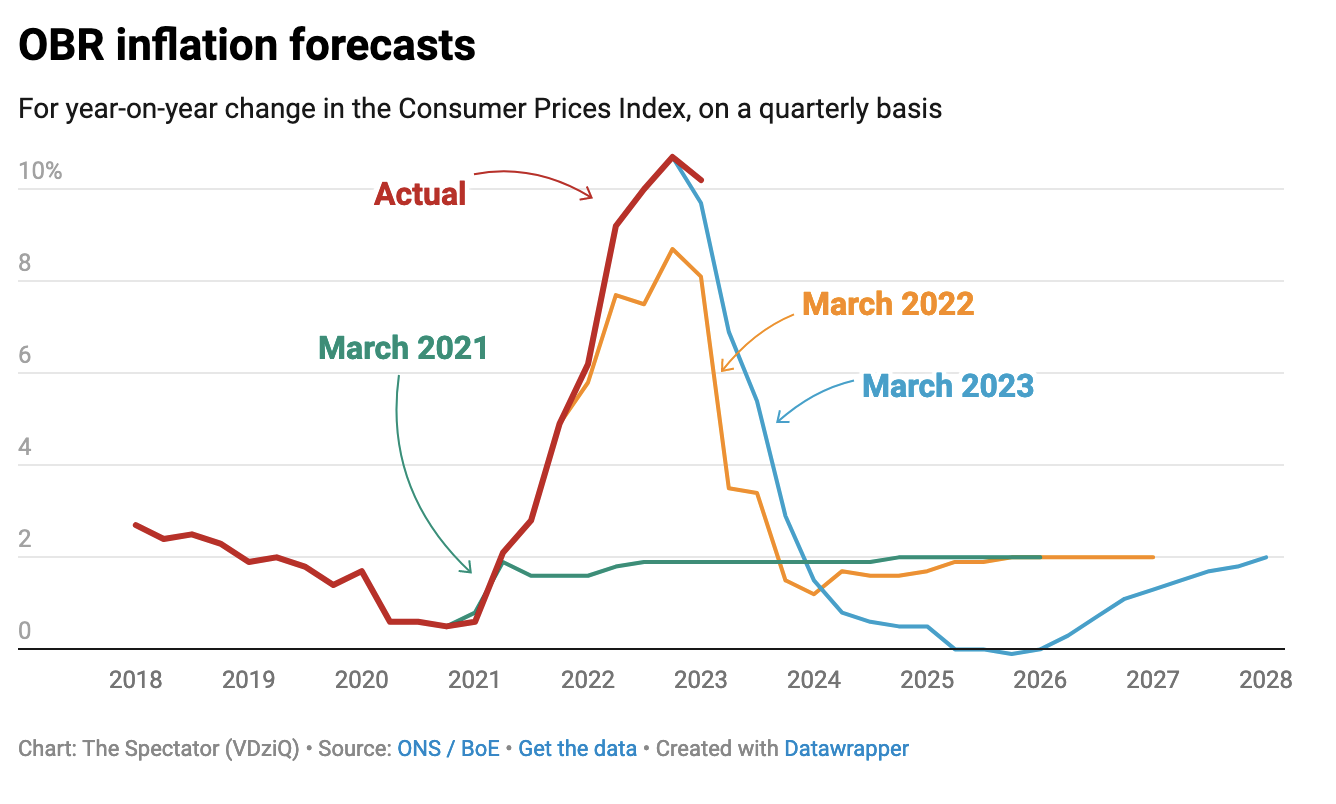

But how much use would a judgement by the OBR have been in any case? Let no one say that the organisation has no insight into its own failures. Today it has published a mea culpa on the forecasts it made in March 2021 and March 2022, both extremely important as the first informed a Budget and the second a spring statement. Like Michael Fish and his non-forecast of the 1987 hurricane, it is an exercise in explaining how things went so horribly wrong.

Both forecasts, the OBR recognises, significantly under-estimated inflation and over-estimated economic growth. In March 2021, it foresaw inflation as rising no higher than 2 per cent for the duration of that year as well as throughout 2022 and 2023. By the end of 2022 that forecast was a whopping 8 per cent out. The forecast made in March 2021 for economic growth in 2022/23 was not a lot better, over-estimating growth by 3.3 per cent. Government borrowing was £21.5 billion higher in 2022/23 than had been forecast in 2021.

Unsurprisingly, the OBR blames the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Fair enough. We expect the cream of OBR economists to be experts in money supply and so on; it would be a bit too much to expect their forecasting skills to extend to what is going on inside Vladimir Putin’s head. And true enough, the Ukraine invasion had severe consequences for the global economy as European countries boycotted Russian oil and gas leading to a surge in energy prices.

But is it really fair to say, as the OBR does, that its March 2021 forecasts can ‘be thought of as a counterfactual for what might have happened if the invasion had not taken place’? That rather suggests that the OBR still thinks it would have been spot on had Putin kept his tanks parked within Russia.

The OBR does say that it is going to have another look at its inflation models, as well as develop a deeper understanding of receipts for self-assessment income tax and onshore corporation tax. But isn’t the real problem that the OBR fails to make any allowance for political events when it is trotting out incredibly detailed economic forecasts for several years ahead? It might have been difficult to foresee the events in Ukraine, but they are hardly a one-off, once-in-a-century cataclysm. Events like that are happening all the time, not least in the Middle East in the past fortnight.

Yet ignoring Harold Macmillan’s remark that governments are constantly undermined by ‘events, dear boy’, the Chancellor faithfully trots out the OBR’s forecasts ever Budget time as if they were forecasts of planetary alignments – which really can be forecast years ahead. The truth is that economic forecasting is a mug’s game. Governments would be better equipped to deal with, or even avert, economic turmoil if they took less notice of fairweather forecasts and instead asked themselves: what is the very worst that could happen over the next few years and how can we defend ourselves against it?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in