My recent Spectator Australia article, Labor’s revolutionary agenda to destroy Australia, gave an overview of the Albanese government’s Industrial Relations Bill, also known as the Loophole Bill, currently before the Senate. Like the ill-advised Voice to Parliament referendum, the Loophole Bill aims to overturn the fundamental laws and institutions under which we are governed.

The Voice was an attack against the Constitution. The Loophole Bill constitutes a major attack against the legal basis upon which our economy and society is structured. We will look at how the Bill erodes the concept of a commercial contract and in doing so, upends the core philosophy that underpins commercial activities in Australia.

But first, we must consider the overarching question raised by this Bill: Should individuals be allowed to earn their income through commercial contracts?

Earning an income through commercial contracts defines a small business. The Albanese government’s answer to that question, as revealed by the Loophole Bill is, ‘No!’ The Labor Party genuinely does not want this sort of employment to exist.

In other words, this is a deliberate attempt to destroy Australia’s self-employed and small businesses community. It’s an aggressive move from the government against the right of Australians to be self-employed – to be their own boss. At a minimum, this is an attack against the incomes of 1.2 million self-employed Australians. These are pretty bold assertions, but they are supported by the structure and wording of the legislative proposal.

I’m not a lawyer, but we need to set the legal scene.

There’s a legal process called the multi-factorial test.

Since the time of the second world war, when deciding whether a person is an employee or a self-employed independent contractor, Australian courts have used what is called the ‘multi-factorial’ test. This test involves a detailed legal analysis of all the factors and behaviours involved between the parties to a work contract.

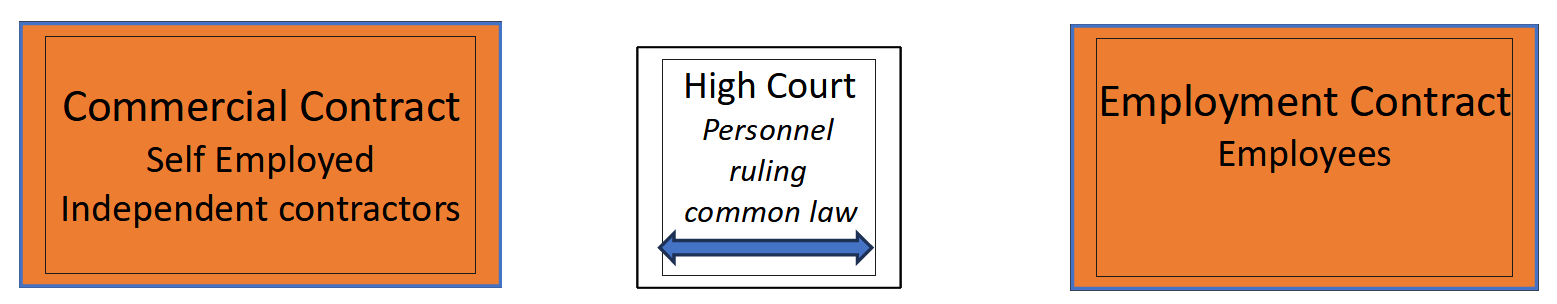

The court process essentially looks to determine whether one person ‘has the right to’ or does ‘control’ the other person. If there is ‘control’, there is an employment contract (called contract of service). If there is ‘offer and acceptance’ where there is no ‘right to control’, the contract is a commercial contract (called contract for services).

Lawyers love this multi-factorial process because it’s complex and generates large legal fees. (I apologise to my dear lawyer friends, but they do admit I’m correct on this!)

But the High Court has declared the written contract to be king, thus throwing a bit of a spanner into this multi-factorial (lawyer money-making) machine.

In February 2022, the Australian High Court (in the Personnel case) dared to take what some consider a massive leap. All seven High Court judges agreed that if a written contract is clear and comprehensive, then the written contract alone should be relied on. This ruling breaks from the complexity of the multi-factorial test.

It seems that the High Court had observed the confusion, complexity and cost associated with the prevailing legal multi-factorial processes and sought to create certainty. The court stated:

‘…it is the task of the courts to promote certainty with respect to a relationship of such fundamental importance.’ (Paragraph 58 of the HC Ruling)

Well, thank damn goodness for that! Isn’t ‘certainty’ something we need from the law?

But ah! apparently not, says the big army of lawyers, academics, and (surprise! surprise!) unionists who have declared the High Court’s decision a calamity. This federal Labor government has responded to its support base with the creation of the Loophole Bill which intends to undo this High Court-created certainty.

It’s worth directly quoting the clause in the Bill. The relevant clause states:

15AA Determining the ordinary meanings of employee and employer

(1) For the purposes of this Act, whether an individual is an employee of a person within the ordinary meaning of that expression, or whether a person is an employer of an individual within the ordinary meaning of that expression, is to be determined by ascertaining the real substance, practical reality and true nature of the relationship between the individual and the person.

(2) For the purposes of ascertaining the real substance, practical reality and true nature of the relationship between the individual and the person:

(a) the totality of the relationship between the individual and the person must be considered; and

(b) in considering the totality of the relationship between the individual and the person, regard must be had not only to the terms of the contract governing the relationship, but also to other factors relating to the totality of the relationship including, but not limited to, how the contract is performed in practice.

Note: This section was enacted as a response to the decisions of the High Court of Australia in CFMMEU v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1 and ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek [2022] HCA 2.

This clause is effectively a legal description of the multi-factorial test. This will override the certainty that the High Court says is of such importance. Look at the ‘note’ which states the clear intention is to override and neuter the High Court ruling. In the Spectator Australia last year I cautioned that Albanese’s Labor would likely seek to neuter the High Court. That’s exactly what Albanese’s Bill seeks to do.

To repeat, the Loophole Bill will subvert, and is intended to subvert, the High Court’s Personnel ruling. It will impact all self-employed people and many more. The words in the Bill show this.

Let me take this understanding a touch further.

The defining difference between an employee and a self-employed independent contractor is surprisingly straightforward.

An employee earns their income using the employment contract.

A self-employed independent contractor earns their income using the commercial contract.

Whether the employment or commercial contract is being used is determined in common law through the process decided on by the courts. The common law is often referred to as the ‘ordinary meaning’ which is the expression in the Bill above.

This diagram shows it all.

This simple reality is often lost in the confusion created by a lot of legal and political commentary.

Take another step.

The employment contract is regulated through industrial/workplace relations statutes.

The commercial contract is regulated through commercial and competition statutes.

Again, this is often shrouded in confusion.

This split between the employment and commercial contract permeates and is critical to, the operation of the Australian economy and any free market economy. This is why the High Court referred to this as a ‘relationship of such fundamental importance’.

Clause 15AA of the Bill (referenced above) seeks to do something never before done under Australian statute. That is, the clause would remove common law (as ruled by the High Court) as the defining difference between the commercial contract and the employment contract for the purposes of federal workplace relations statutes. It’s a killer of the core structure of commercial law.

The consequences of this are major.

Have no doubt. This is a trashing of a fundamental part of commercial activity. For those people in our society who aspire to ‘smash capitalism’ this is a pretty good strike in that direction. It smashes the right of people to ‘be their own boss’ and to engage in society as ‘mini-capitalists’ to use such terminology.

Did someone say ‘Marxism?’

I’m no ‘capitalist’. Pure capitalism aspires to allow monopoly. (Oops. I bet I’ll have plenty of Spectator Australia readers debate me on that statement!) But free markets (which I do support) allow for the aspiration towards monopoly but always frustrate its achievement. That’s good. If you’re prepared to at least accommodate my take on free markets, then the following understanding of industrial relations should resonate.

That is, competition law and industrial/workplace relations law have fundamentally opposed objectives driving their different processes.

Competition (commercial) law and regulation are about the prevention of price-fixing, anti-competitive collusion and monopoly in the economy.

Industrial/workplace relations are about the reverse – the implementation of price-fixing (wages) and collusion to enforce that price-fixing.

These two regulatory and legal environments are total opposites. The Loophole Bill seeks to, and will, destroy one side – commercial/competition law – to favour the other side – employment/monopoly law.

Further, 15AA of the Bill creates an irreconcilable clash between them.

A contract could readily be declared a commercial contract based on common law and subject to competition and commercial statute and regulation, yet the same contract could be declared ‘employment’ under 15AA and subject to the statutes and regulation of industrial/workplace relations law. This will create victims who will be caught in a vice between competition and employment regulation. Those victims will be ‘self-employed’ people.

In other words, self-employed, independent contractors (as defined by the High Court at common law) and the businesses/persons who engage them could (and will) find themselves subject to competition law, yet at the same time be forced or required under industrial/workplace relations laws to breach competition law.

There’s much more to say on the issue. In this article I’ve covered just one page of the 284-page Loophole Bill. I’ve lots more analysis to follow that will detail and explain how the structure of the Loophole Bill corrupts the commercial contract.

Ken Phillips is Executive Director of Self-Employed Australia and publishes on Substack.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in