This year’s Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Frans Hals retrospective at London’s National Gallery are testaments to the enduring appeal of the Dutch artists of the Golden Age.

When the 80-year war between Spain and the Dutch Republic ended in 1648, it left the Dutch strong in military and economic terms. They founded colonies across the world. The affluence and stability provided the perfect medium for creativity. Painting flourished, and buying art was no longer the domain of the wealthiest.

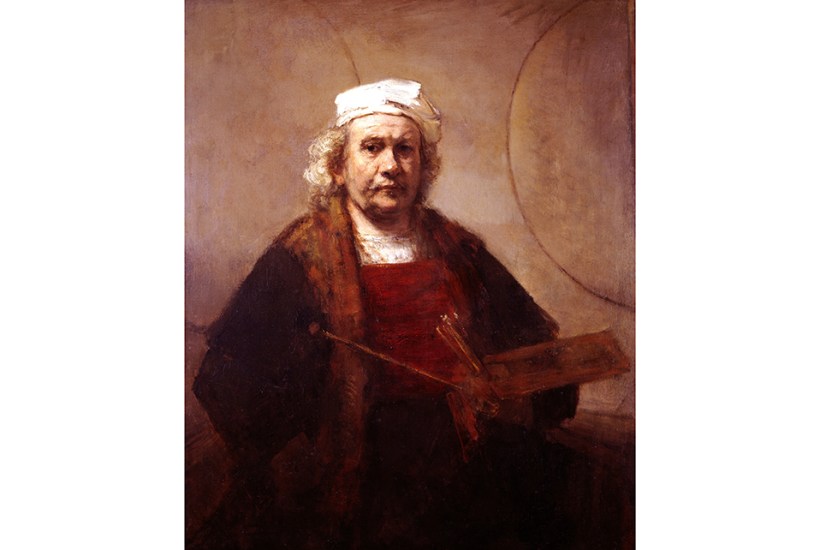

Benjamin Moser’s first book since winning the Pulitzer for Sontag explores this burgeoning world. The lives and works of the greatest and lesser-known Dutch artists of the era are here: dark drama and chiaroscuro from Rembrandt; exquisite serenity, teasing intrigue and light from Vermeer; warmth and mischief from Frans Hals’s portraits; and emotive beauty from Fabritius, who was killed in his prime by the explosion in Delft in 1654. There are genre paintings from Ter Borch, with his eye for the sheen of satin, and vibrant colours and glossy materials in Metsu’s peaceful home scenes. There’s understated domestic contentment from De Hooch and bawdy hedonism from Jan Steen, frequently featuring his own dissolute self. There are ice-skating vistas with scabrous details from the deaf and mute Avercamp; tranquil church scenes and mastery of perspective from Saenredam and livestock from Potter. The are Ruisdael’s magical transformations of flat, marshy terrain into brooding landscapes; Ruysch’s flowers (she’s the only woman artist featured here); Coorte’s tiny still lifes and Eckhout’s representation of indigenous people in Dutch colonies in Brazil.

The story is also of Moser’s own journey finding out about these painters. Thus, when he first mentions Pieter de Hooch, he tells us that the artist died in an insane asylum. Hold on, I thought, wasn’t that his son? Sure enough, Moser takes us to the moment when art historians first made this discovery.

Many interesting facts are gradually revealed. Out of three different paintings, by Metsu, De Hooch and Vermeer, of a woman weighing precious items on a tiny balance, most would pick Vermeer’s as the most awe-inspiring for its technical prowess, beauty and enchanting tranquillity. So were the other two followers? In fact they painted their versions before Vermeer. The history of art, like that of literature, is one where creatives are constantly stimulated and influenced by the work of others.

This makes for a form of symbiosis whereby exploration of a new theme by one artist can lead to variations on that theme by others. It also explains the order in which artists are examined in this book. I expected the giants to be discussed first, then the more peripheral figures. But Moser intermingles great and lesser names so that we can make direct comparisons between the work of a master and his followers.

Rembrandt, for example, used chiaroscuro to bring shock and violence to his work, whether in his series of self-portraits from youth to skull-like old age or in the fury or terror on the faces of many of his figures. But compare his version of ‘The Sacrifice of Isaac’ with that of his student, Ferdinand Bol. Rembrandt’s is shocking: Isaac’s neck is forcibly exposed so that the dagger can slice it. Bol’s is anodyne by comparison. But which would you rather face every day? It’s easy to see why Bol made a fortune in his lifetime while Rembrandt, despite intermittent success, died in poverty.

The fascinating details keep coming. Did you know that Frans Hals was sued at least ten times for being unable to pay for basic food, clothing or rent? Or that Pieter Bruegel’s ‘Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap’ coincided with the beginning of a Little Ice Age? The dropping temperature also explains the ubiquity of ice skating in Avercamp’s work.

I don’t always agree with Moser. He finds Jan Lievens’s ‘Penitent Magdalene’ ‘repellent’ and ‘disgusting’ because of her swollen fingers. I think they are a clue to her manual labour – a telling detail, like the dirt on the feet of a worshipper in Caravaggio’s ‘Madonna of the Rosary’. But this book is a joy. Read it with your smartphone and look up every painting discussed in full colour.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in