SPI-M-O are at the Covid inquiry this week. They’re the shadowy group of mathematical modellers who contributed – more than most – to the evidence that backed up lockdown. On Monday we heard from Professor Mark Woolhouse of Edinburgh University. Surprisingly – for an inquiry that seems from the outset to be focused on the deaths of the vulnerable and how we should have ‘locked down sooner’ – Professor Woolhouse focused his evidence on the mistakes of lockdown.

Lockdown was ‘disproportionate, unsustainable and not as effective as was being claimed’, he told the inquiry. He also said they were ‘a failure of public health policy’. Blame lay with the government, who had simply failed to ask the modellers to come up with anything different.

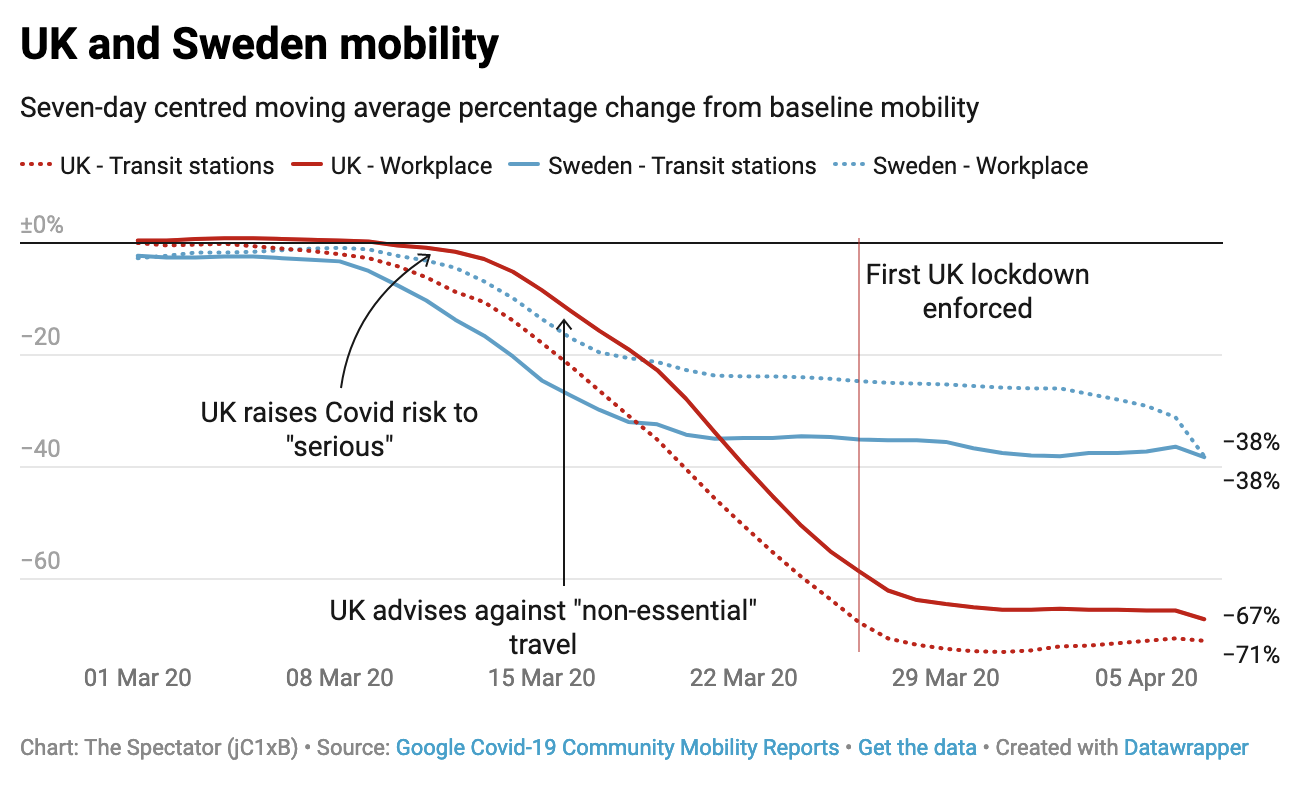

Brits – like Swedes who avoided a full lockdown – kept themselves to themselves in response to the ever gloomy news from Italy and closer to home

Today it was back to script as Professor Neil Ferguson took the stand. Ferguson had supplied the inquisitors with an 105-page witness statement, and seemed desperate to lose his association with lockdown.‘I know I’m associated very much with a particular policy’, he said. At one point the interrogating KC even quipped: ‘You call it mandatory [restrictions], professor. But we all know we’re talking about a lockdown’.

Much of the KC’s questioning seemed focused on the accusation that Ferguson and his scientific colleagues had not done enough to raise the alarm around the pandemic. ‘Where was that warning?’, the KC demanded. This was a staggeringly unfair assertion, given how frequently Professor Ferguson could be found proclaiming imminent doom on the Today programme.

Bizarre though it was, this line of questioning proved fruitful in other areas. The official position from Ferguson, and almost all scientists involved in Covid and lockdowns, is to hide behind the structure of Sage. They could only answer the very ‘narrow’ questions that the government asked of them they say. So, if the government did not directly ask them ‘should we lock down’ or ‘what are the wider costs of doing this’, they could not answer. The inquiry’s barrister didn’t accept this defence.

He pointed to page upon page of evidence from private emails Ferguson and other modellers had expressed views on policy to members of the government – usually the chief medical and scientific officers. It was this line of questioning that – although surely not what the KC was getting at – led to the most worrying conclusion. Lockdown became a both inevitable and unstoppable force. Indeed, as Ross Clark points out, the decision to lock down happened without anyone bothering to check what the NHS could actually cope with.

The interesting parts of the professor’s evidence though came largely as an aside just before lunch. The KC wanted to know if modelling had factored in how different population groups were affected by pandemic measures. How effective would stay at home orders be among different ethnic groups, for example. ‘None of the models looked at the indirect consequences of interventions’, came the reply. The lawyer had his answer and moved on. But this seems a staggering confirmation of what has been clear for some time.

None, not a single one, of the models that led to the biggest legally enforced restrictions of our freedom since the war considered what side-effect those lockdowns might have. Those effects have now become painfully clear: record excess deaths, school absences, sky-high anxiety, missed cancers and worklessness. Those factors were never once considered by those pushing the decisions that got us here. ‘Did anybody take any steps, to say, in the context of Sage or to the government? We need to have a structure for working out the cost benefit of the measures which – god forbid – might have to be considered’, asked the KC. ‘I can’t think of an instance of that happening’, replied Ferguson.

Perhaps he is due a modicum of credit here though. The emails examined in his evidence showed he was aware of this fatal flaw at the time. In one email with Downing Street he wrote: ‘This event is in the natural disaster category and the cure (e.g. massive social distancing, shutdowns) could be worse than the disease.’ The inquiry lawyer seemed to think this somehow inappropriate. But the KC did not seem keen to press the point.

That was left for the end of what was a very long evidence session when a lawyer representing various children’s charities finally looked at some of lockdowns’ cost. He pointed to a passage in Ferguson’s witness statement that said Sage were never asked to come up with interventions that would have minimised economic and social effects. Could that have been done if the government had requested it? ‘Yes’, came the reply.

None of these reservations stopped Ferguson’s team at Imperial producing figures for countries all over the world about what would happen if they failed to lockdown. Figures that proved overly pessimistic time and time again. Sweden, for example, would see 85,000 deaths but ended up with less than a third of that.

Another key point the inquiry would do well to spend time on featured only briefly: the behaviour changes people would make of their own accord. It was hardly considered that Brits might regulate themselves in such a way that a legally enforced lockdown – a lockdown that is still chasing people through the courts today – might not have been needed. There are no such ‘validated’ models to do that, said Ferguson. Indeed he himself pointed this problem out in an article in Nature in 2006. ‘We do not assume any spontaneous change in the behaviour of uninfected individuals as the pandemic progresses but note that behavioural changes that increased social distance together with some school and workplace closure occurred in past pandemics and might be likely to occur in a future pandemic even if not part of official policy,’ he wrote back then. So nearly 15 years before Covid struck Ferguson knew how crucial self-governed behaviour change might be and how unprepared modelling was to take account of it.

In the end the data bore this out. Brits – like Swedes who avoided a full lockdown – kept themselves to themselves in response to the ever gloomy news from Italy and closer to home, as the below graph shows.

We can only hope that at some point in the many years of this inquest we’ll get a more in-depth examination of flawed modelling. The vital question they need to ask is were flawed models better than nothing at all? As Nassim Nicholas Taleb said of flawed financial risk models: ‘You’re worse off relying on misleading information than on not having any information at all. If you give a pilot an altimeter that is sometimes defective, he will crash the plane. Give him nothing and he will look out the window.’ Might the same have been true of Covid models?

Toward the end of Ferguson’s evidence session – once the KC had returned to the bizarre idea that the professor and his colleagues had not raised the alarm – came the key point. A point that this inquiry seems almost designed to miss. ‘Was that [first] lockdown necessary?’ ‘This is not a question we can definitively answer, the professor replied. Would voluntary measures have been enough? ‘We’ll never know.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in