Twenty-one years ago, when I was a young Labour MP, I wrote a piece in these pages about going blind. I described a rare degenerative eye condition called choroideremia, which shrinks and darkens one’s vision until eventually there’s nothing left. I started to see less in my late teens; by the time I wrote the piece in 2002 I was 33 and perhaps half-blind, but could still manage to do most things pretty well.

The daily differences were such, though, that people could tell there was something not quite right. I would do things – such as failing to see, and therefore to shake, an outstretched hand – which just seemed odd. I worried that my bumping into and tripping over things all the time would make people think I was drunk. As I quite often was drunk in those days, I really didn’t want people thinking I was when I wasn’t.

Instead, I wanted people to know that I couldn’t see properly, but I didn’t want to have hundreds of awkward conversations about it. Indeed, I didn’t want to talk about it at all. So I wrote about it.

People were very kind. Tony Blair sent a long, sincere, handwritten note. David Blunkett, who was then home secretary and whom I didn’t really know, had me over for sandwiches and an avuncular chat. That hour with Blunkett has stayed with me: furtive kindness masked by iron rigour and resolve.

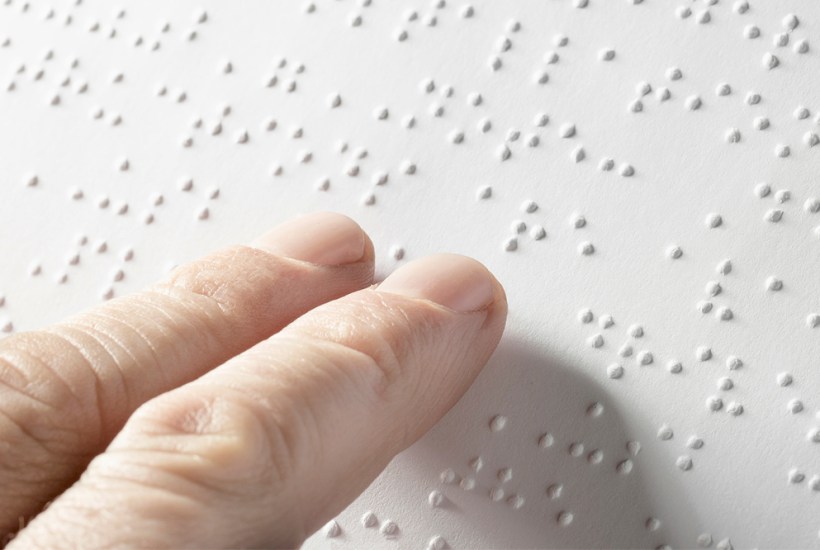

I asked him how, when winding up parliamentary debates, he made notes on all the speakers, as parliamentary practice dictates, while sitting on the front bench without his Brailler. He explained that he had a little stylus, like a bookie’s pencil, with which he pushed up from underneath the Braille dots of his prepared speech. To do this, he clarified, you must be able to write Braille dot-by-dot, upside down, in a mirror image. He learned when he was five.

People are still kind to me. These days I use a symbol cane: not the long one with the bobble that you see blind people tapping from side to side, but a short one that you just hold out in front of yourself as you walk. Its only purpose is to let people know that you can’t see, yet the positive effect is hard to overstate. Without it, I would really struggle to get about. Even with a cane it’s stressful, but everywhere I go, once they can see that I’m blind, almost everyone accommodates and there is always someone who actively offers help. If I had ever lost it, it would have restored my faith in humanity.

I still have some sight left for now but feel entitled to call myself blind because this summer saw me finally registered as such. It has been a great moment of validation. One of the problems of losing my sight gradually has been always feeling that I wasn’t quite blind enough. Now I have a certificate of authenticity, and I feel better for it.

I know that to think this way is the anti-thesis of the ‘social model of disability’ in which everyone’s impairment is valid and shouldn’t need to be corroborated. In principle I largely agree; it’s just not my own experience. Which leaps out as evidence that I have ‘internalised ableism’. In other words, that I have adopted the dominant societal beliefs that disability is shameful, and that people, particularly with invisible disabilities, could well be lazy scammers. I’m sure ‘internalised ableism’ is a real thing and there’s no reason I should be immune; I clearly do have the symptoms.

Yet I don’t think it’s quite that simple. Everyone knows that feeling when you trip and go flying and really hurt yourself, that moment in which you feel not just fury but also deep, hot-faced shame. These days my whole life feels like this. As much as the actual injuries, a thousand smaller humiliations seem like minor versions of that same primal feeling: that you’re exposed and at risk because your body doesn’t work the way it should.

One is not supposed to say ‘it should’, but I don’t think I’ve merely internalised society’s view that there’s something wrong with me. My experience reminds me every minute that one of my basic senses doesn’t work, that there are many vital things I can’t do which almost everyone else can; that, in fact, there is something wrong with me. I’d like to feel allowed to say that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in