In 1348, the year the Black Death reached England and devastated the country, Matilda, the wife of Robert Comberworth, attacked someone called Magota and drew blood. She was fined 3d. Agnes, the wife of William Walker, attacked William de Pudsey and was fined four times the amount. Amica, an official watch-woman tasked with guarding a fruit crop, caught a certain Cecilia stealing. These women are among the many who star in Philippa Gregory’s latest book.

Post-Conquest England is well-trodden ground, but Gregory’s history is not one of great men. It is of normal women – the women of legal battles, petitions, wills and letters. Her characters farm, pray, heal the sick, revolt and go to war. They are mothers, political agents, activists and victims. They are 50 per cent of the population over 900 years.

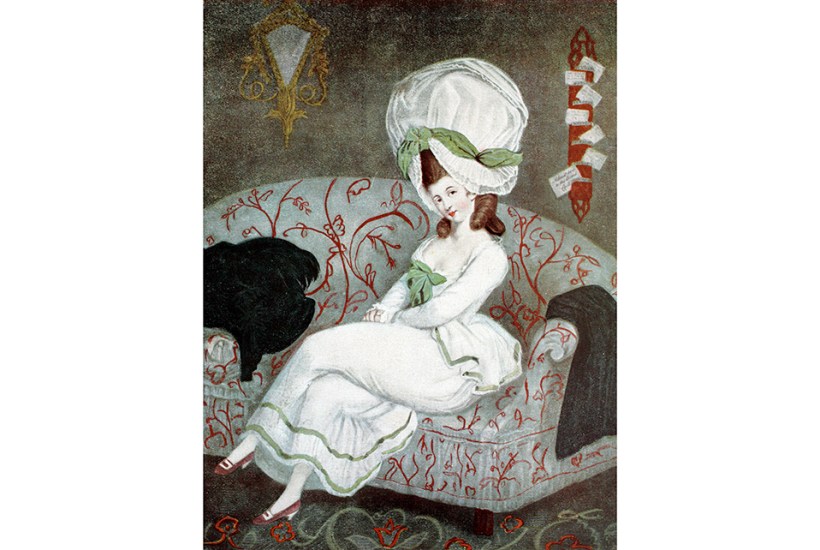

The Norman Conquest was ‘Doomsday for women’, according to Gregory. The Normans introduced oppression painted with a veneer of legal tradition. Women were excluded from inheritance and generally undervalued and undermined. Gregory notes that the Bayeux Tapestry has ‘more penises on it than it does women: 88 on the horses and five on the men’, one of whom is naked, chasing a woman from a burning house. But this history is not one of female victims (though domestic abuse and sexual violence certainly figure) but of women who demonstrated agency in multiple ways.

We see them involved in the business of credit, such as the 13th-century Jewish English moneylender Licoricia of Winchester, who became ‘one of the country’s greatest financiers’. The textile industry also had a strong female element. In 1239, Henry III commissioned Mabel of Bury to create an embroidered standard for Westminster Abbey. At a humbler level, women bartered goods and took seasonal jobs such as sheep shearing and harvesting. The physical labour was often immense. Gangs of women in the charcoal business ‘went into the forest to cut or gather firewood, turning it into charcoal by controlled burning’, a task which took days to complete.

Other examples of enterprise included prostitution. Elizabeth Brouderer was accused of running a brothel in 1394, and admitted to sex with ‘three scholars of Oxford, two Franciscan monks, six foreign men, a woman called Joan’, and (dressed as a man) with ‘many nuns’. When venereal disease emerged in the 16th century, ‘unchaste women’ were blamed, and sex work was prohibited – until the accession of Charles II, when prostitution was one of the many hedonistic activities he legalised.

More surprising is the extent to which women were involved in rebellion. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 began with Joan Hampcok and Agnes Jekyn from Kent. At its peak, another formidable Kentish woman, Johanna Ferrour, called for the beheading of the Archbishop of Canterbury after the rebels dragged him from the Tower of London.

Gregory describes how those who’d chosen a cloistered life suffered during the Reformation, with ‘women-only traditions… lost in the Dissolution’. Displaced from the haven of their convents, they were cast into a Protestant, man’s world where only a woman who’d had intercourse was considered ‘womanly’. Some, faced with renouncing their Catholic faith, chose martyrdom, among them Margaret Clitherow of York, crushed to death over an agonising 15 hours. There were cases of heavily pregnant women going to the stake.

Gregory’s pervading theme is that women kept on fighting. They resisted the 17th-century Enclosure Acts, by which previously common land could be bought by wealthy landowners who charged impossible rents, and the Corn Laws in the 19th century, which banned cheap wheat imports that could have fed the poor. And of course they fought the Nazis, often as spies.

Finding evidence of women in the record is challenging, but Gregory places centre stage decades of scholarship in women’s history, a genre that started to become important only in the 1970s. Voices of the past can be heard through careful analysis of the fragments that do exist, and reading a document ‘against the grain’ of its author’s intention often reveals crucial details. This celebration of women is a triumph of popular history.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in