Speaking at the Centre for Policy Studies fringe event at Conservative party conference this afternoon, Jeremy Hunt reiterated once again that there would be no big tax cuts this year. ‘Debt interest payments have gone up so much in the past six months’, he told CPS director Robert Colvile, taking estimates for debt servicing payments over the £100 billion mark this fiscal year. The Autumn Statement, the Chancellor said, will lay bare just how dire the situation is: ‘It’s likely that our debt interest payments… are going to go up by more than £20bn pounds a year in the Autumn Budget compared to what was predicted in the spring.’ In other words: no tax cuts until inflation stops wreaking havoc on borrowing costs.

What triggered the inflation crisis that has caused so much damage to personal and public finances? There are many reasons cited, but some suit certain agendas better than others. Both ministers and central bankers have worked hard over the past year to point the finger at factors out of their control. In the government’s case, it tends to cite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the Bank of England’s case, it cites the war, as well as accusations of a ‘wage-price spiral’ (despite wages increasing for over a year well below the rate of inflation).

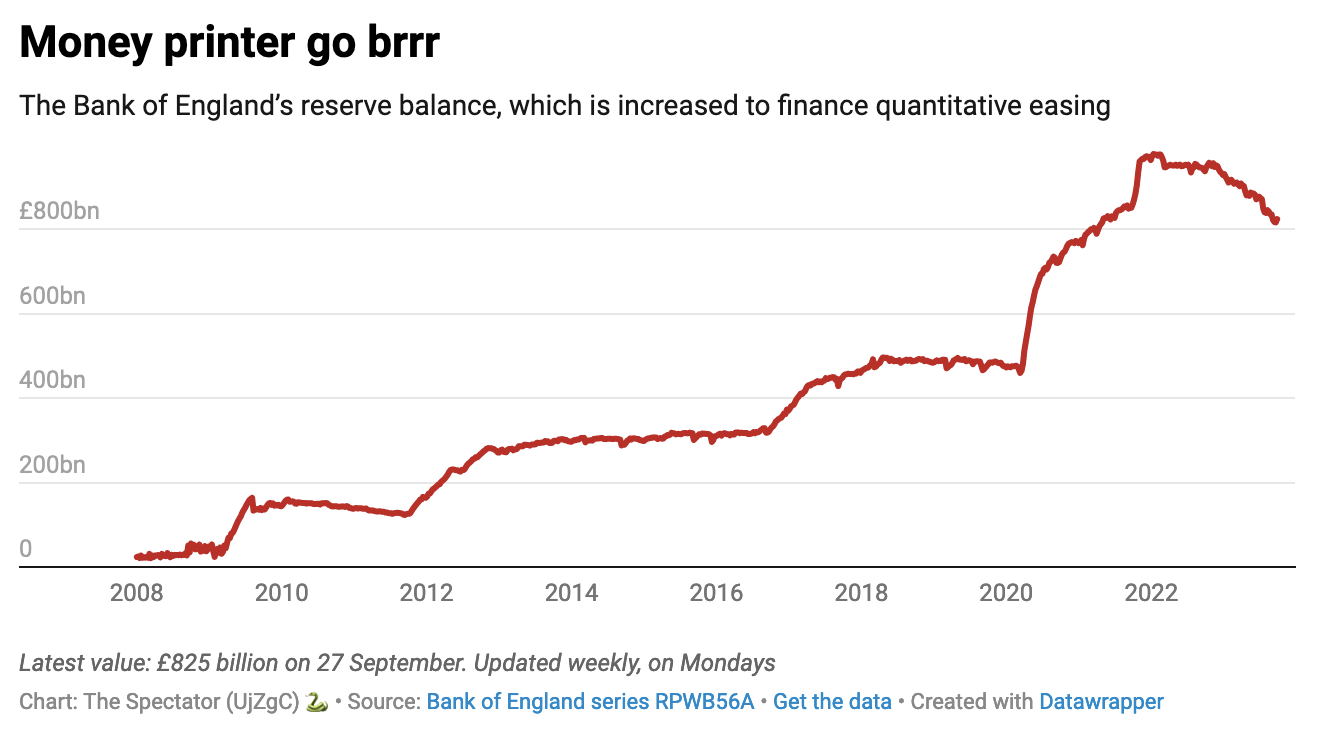

What’s often left off the list is what happened at the start of the pandemic: a mass money-printing exercise carried out by central banks to allow politicians to spend without limits. In Britain, the Bank printed more in the first year in the pandemic than it did in the ten years leading up to it. As inflation tends to be a monetary phenomenon, it makes sense that quantitative easing had a direct impact on price spirals, and some are willing to point this out.

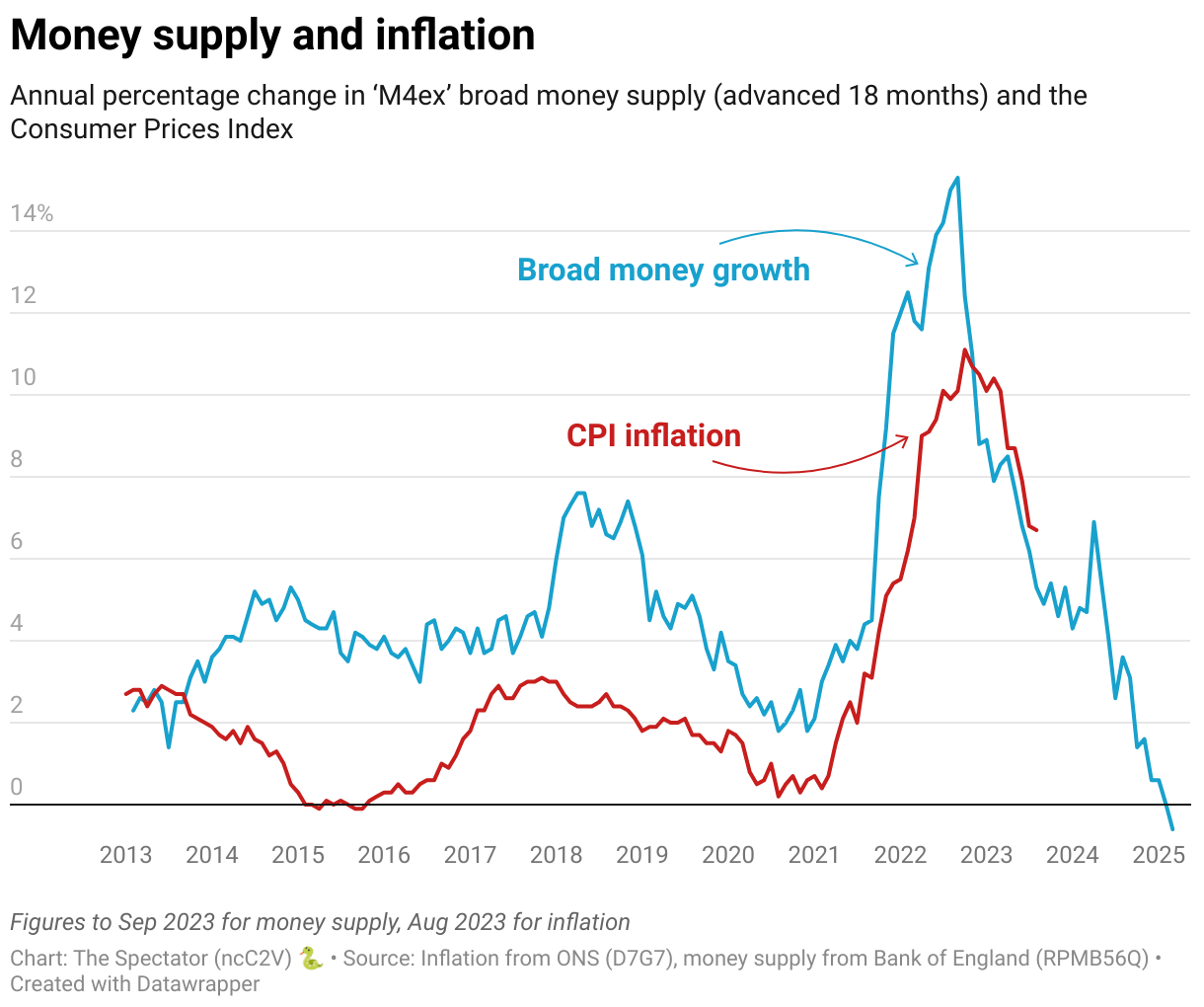

Former chief economist to the Bank Andy Haldane was warning about the effects of money-printing on prices back in June 2021, when the rate of inflation was just starting to rise. Former Bank governor Mervyn King has been saying since last year that ‘too much money’ contributed to the inflation spiral. Economist Julian Jessop wrote on this topic for Coffee House last month, noting how the annual rate of inflation has roughly followed the growth rate of broad money. Yet it’s been in the interest of both ministers and central bankers to avoid addressing the role of money-printing directly: better for the crisis to be something they’ve been forced to respond to, rather than something they helped to cause.

But this afternoon Jeremy Hunt cautiously added his name to the list. Asked what he thought had contributed most to the inflation crisis – the war in Ukraine, money printing or a wage spiral – he said:

I hate ducking questions. I don’t think it’s quite as straightforward as ranking them one, two, three. I’d definitely put Russia’s war in Ukraine at the top of that list. I think that quantitative easing…I think it is reasonable to say we collectively underestimated the impact of that. Although in fairness to the Bank of England they did start to raise interest rates before everyone else.

Threadneedle Street did move first to raise rates, but once other central banks like the Federal Reserve followed suit, they did so faster and more aggressively than the Bank of England: a move which is now thought to have helped get America’s inflation rate down to almost half that of Britain’s. Indeed one of Hunt’s predecessors – and now boss – Rishi Sunak was well aware of the possibility that QE could trigger an inflation surge: long before Russia’s invasion, chancellor Sunak was working to protect the UK’s finances from the prospect of even a small hike in the rate of inflation back in spring 2021.

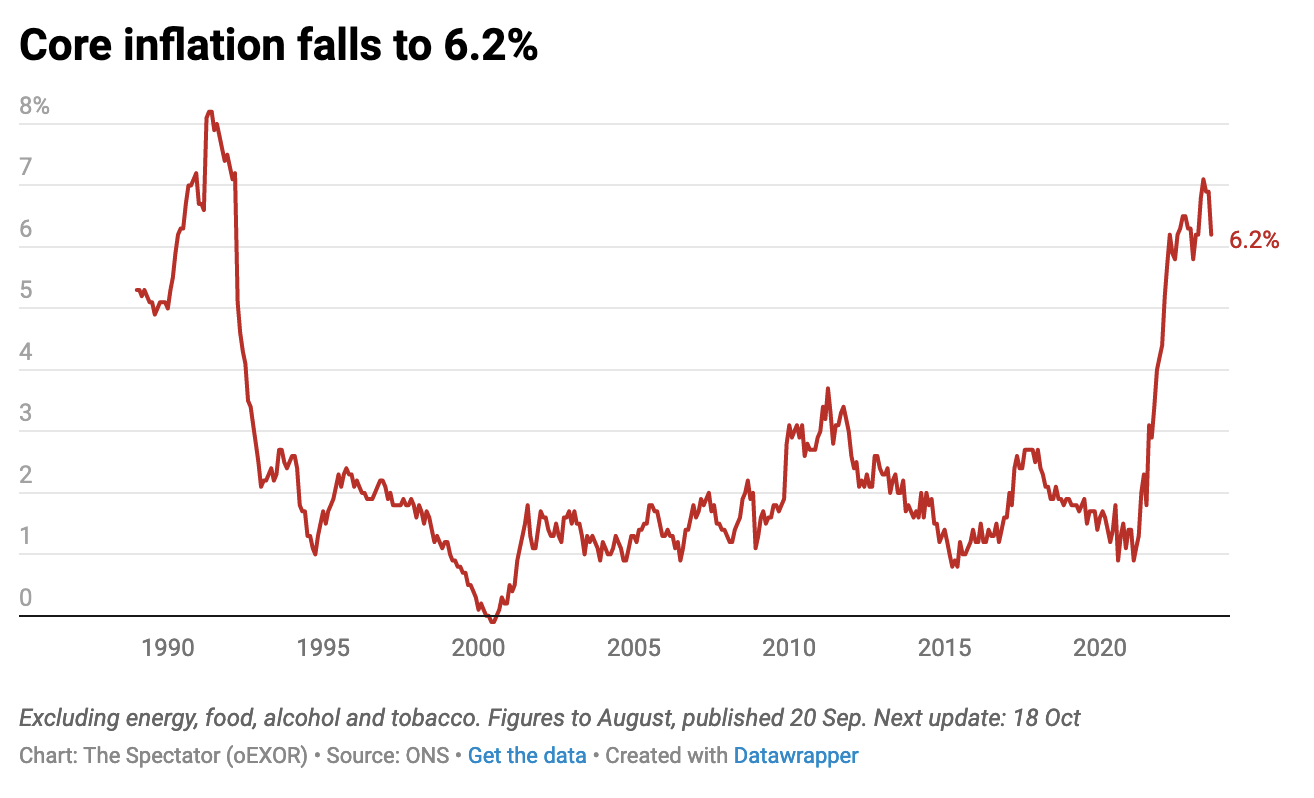

The evidence is there: while falls in energy costs have seen the headline inflation rate come down, inflation was more than double the Bank’s target months before Russia’s invasion. Furthermore, the huge rise in core inflation (which excludes food and energy prices) suggests the inflation crisis has been triggered by much more than energy costs: it has slowed from a peak of 7.1 per cent on the year to May to 6.2 on the year to August – still triple the Bank’s target.

Tackling inflation remains Hunt’s priority. What are the prospects for tax cuts once that’s achieved? ‘All Tories want tax cuts’ he told the CPS’s audience. ‘But we need to focus on how we get there.’ For the chancellor, the answer lies in public sector efficiency gains. ‘If we want to stop taxes going up,’ he said, ‘we have to increase productivity growth in the public sector by half a per cent a year.’ For those with experience in the private sector, he said, the attitude is that ‘surely we can do that.’ Yet ‘those of us who have worked in the public sector know that’s a very big challenge… but we have to do it.’

If Hunt does find some fiscal headroom, what will those first tax cuts be? The ‘first priority’ he said, is ‘business tax cuts.’ It’s likely Hunt would look at the current ‘full expensing’ scheme to encourage more business investment, telling the CPS today that ministers ‘absolutely do want to make it permanent.’

On personal tax, the Chancellor expressed his hope that ahead of an election something could be done for ‘ordinary people’ to ‘show people our values and that we believe money is better when it stays in people’s pockets.’ Still, he insisted at the moment the Treasury is not in a position to have that discussion ‘or even to ask what if’.

The clock is ticking.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in