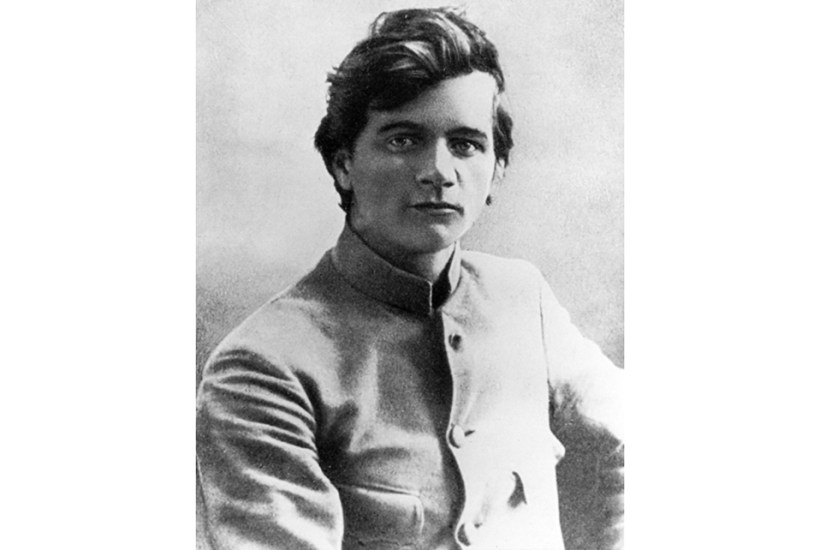

It has been a long journey into the light for the greatest Russian modernist most people have probably never heard of: Andrey Platonov. Born in 1899 in Voronezh, he started professional life as a mechanic and land-reclamation engineer, making him one of those rare writers with an affinity for both people and machines. In the mid-1920s, he was branded an ‘anarchic’ spirit by Maxim Gorky, who nevertheless admired his work. His great early novels were openly critical of the Soviet policy of ‘total collectivisation’ – which, in Platonov’s nightmare scenarios, tends to collectivise people to death. The best and longest, Chevengur – now available in a handsome translation, with an abundance of fascinating historical notes – wasn’t properly published in his lifetime, partly because he was relatively unknown but also because he was being read by the wrong people. (Stalin reportedly scrawled ‘scum’ in the margin of one of his early stories.)

Based on Platonov’s experiences touring collective farms in the Volga, Chevengur follows the converging storylines of Russia’s poorest people in the early 20th century, along with some of its most nobly aspiring community organisers and its most horrifically destructive political apparatchiks. They live and work in small towns and rural hamlets where many subsist on nothing but sunflower seeds and fantasies of fulfilment about a collective Soviet future that, as they soon learn, turns out to be built on the bodies of slaughtered kulaks and bourgeois landowners.

The central character, Sasha Dvanov, is an orphan. As he searches for a home in an endlessly hungry world, he encounters political thugs, ideologues and highway robbers belonging to both Red armies and White. Yet – like his creator – he never gives up believing in a beautiful future even when he watches it being built on a rocky, arid historical present that looks irredeemably ugly.

Chevengur describes a utopian community that might have improved on our sorry world if not for the horrible crimes that brought it into existence. It’s a modernist parable that sometimes feels fractured by too many characters, disorienting time shifts and a fair share of redundancies (such as the too-often recurring ‘joke’ of a zealous ideologue named Kopionkin, who rides around on a horse named Strength of the Proletariat and dreams of being romantically united with the ghost of Rosa Luxemburg); but it’s still hard to read a page without encountering passages of rare beauty. Sasha, while acquiring some unwelcome knowledge in his various journeys, reflects:

Inside every man there also lives a little onlooker – he takes no part either in his actions or in his suffering and is always dispassionate and always the same. His work is to see and to witness, but he has no say in a man’s life and no one knows the reason for his solitary existence. This corner of a man’s consciousness is lit up day and night, like the caretaker’s room in a large building. For days on end this ever-vigilant caretaker sits by a man’s front door; he knows all the tenants of his building, but not one ever asks him for advice… In the event of fire, the caretaker telephones the firemen and goes outside to observe fur-ther developments.

Like many of Platonov’s remarkable fictions (now, thanks to Robert Chandler and his translating collective, very available), Chevengur offers contemporary readers a wholly imagined, often surprising and by turns terrifying and delightful world. It is one in which magic realism doesn’t predominate but which is invested by an otherworldly testimony about our dizzyingly unbelievable history, and brought to memorable life by a man who wasn’t afraid of telling all that he knew, believed and hoped.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in