Next year, Exeter University will offer an MA in Magic and Occult Science: the first of its kind in a British university. The new course has led to newspaper headlines about a ‘real-life Hogwarts’ and questions as to whether magic is as worth studying as say, economics. The course director, Professor Emily Selove, refused my request for an interview – with polite apologies, although one could hardly expect the convenor of Exeter’s Centre for Magic and Esotericism to be anything but esoteric.

A similar tension, it turns out, is at the heart of the debate about the degree. For all the media snideness, the most serious objections come from Britain’s growing magical community. In the 2021 census, 95,000 people said they believed in Paganism, Wicca or Shamanism, up from 70,000 in 2011.

Bob Osborne has devoted years to studying the paranormal, particularly around his Cornish village of Zennor, publishing his book Zennor: Spirit of Place earlier this year. He confirms that many magical practitioners are deeply opposed to the course: ‘It’s the popularisation of ancient doctrines that have been hidden for centuries, passed down through a succession of secret societies and bloodlines who have been “initiated”. Adepts have this information, but if the public experiment with rituals it could go very wrong.’

Since Professor Selove won’t speak to me, I decide to explore the south-west’s magical community myself. I meet Bob in the Tinners’ Arms in Zennor. The pub is purportedly haunted by a tin-miner, and there are reports of glasses being raised by poltergeists, even when everyone present is sober. The barman has a pentagram around his neck.

Bob’s main complaint about the university course is the phrase ‘occult science’. He is very much of the opinion that it is an art, not a science. We sit in the pub and he draws connections between the writers and artists who lived in Zennor, such as D.H. Lawrence, Peter Warlock and the occultist Aleister Crowley. He then offers to show me a house above the village probably used by Crowley for rituals. Of course we go: walking through the bracken to the top of Zennor Hill, where huge outcrops of granite look down over the landscape. Beneath this carn is Carn Cottage. There is, in fact, no proof Crowley stayed here, but that has not stopped the abandoned place becoming a site of pilgrimage.

Ivy is insinuating itself through the walls and ceiling, and some of the floorboards have been pulled up to reveal bare earth beneath. Others are daubed with magical symbols: pentagrams in circles, and complicated sigils. I take a photograph of one and tweet it to a folklore expert. He tells me it is not any magical figure he recognises and is ‘almost certainly someone playing silly buggers’. On the walls are more pentagrams, inverted crosses and a surprisingly well-rendered Peter Griffin from Family Guy. There is a huge hearthplace, with evidence of recent fires. ‘I once came and someone was slaughtering a goat there,’ Bob says.

What we do know about this cottage is that in 1938, local magistrate (and neo-pagan) Katherine Laird Arnold-Forster visited and had a fatal cardiac arrest. What caused this in a healthy 51-year-old is subject to more speculation. ‘One of the more outlandish – but not totally unbelievable – stories,’ Bob tells me, ‘is that Crowley summoned an 8ft-tall reptilian creature, with horned wings, and the sight of the demon gave her a heart attack.’

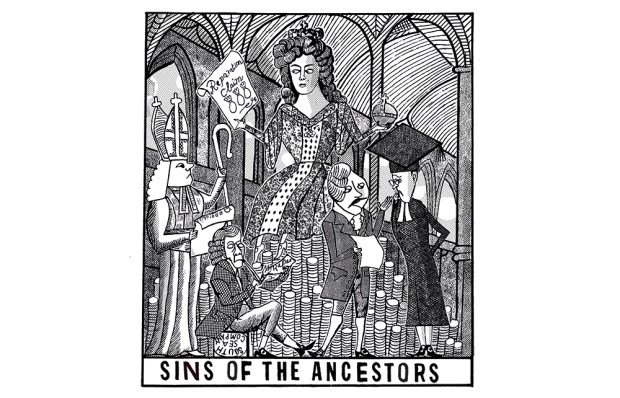

On the way back to the village, Bob asks me how much the Exeter MA pays its lecturers. He may be coming round to the idea of teaching the subject to anyone with an undergraduate degree and a spare £12,000, but many of his friends are still very much against the course. ‘They hate all commercialism of the occult – some of them are still angry about the museum in Boscastle.’

This, the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, grew out of the personal collection of Cecil Williamson, neo-pagan warlock and MI6 agent. Oddly, the ‘career opportunities’ section of the Exeter prospectus mentions museums and academia but not espionage, although there has always been a connection and – Bob hints heavily – there still is. When I drive into Boscastle village, the valley is covered by mist rolling in from the sea. I feel, not for the first time in Cornwall, that I am in the opening scene of a folk-horror movie.

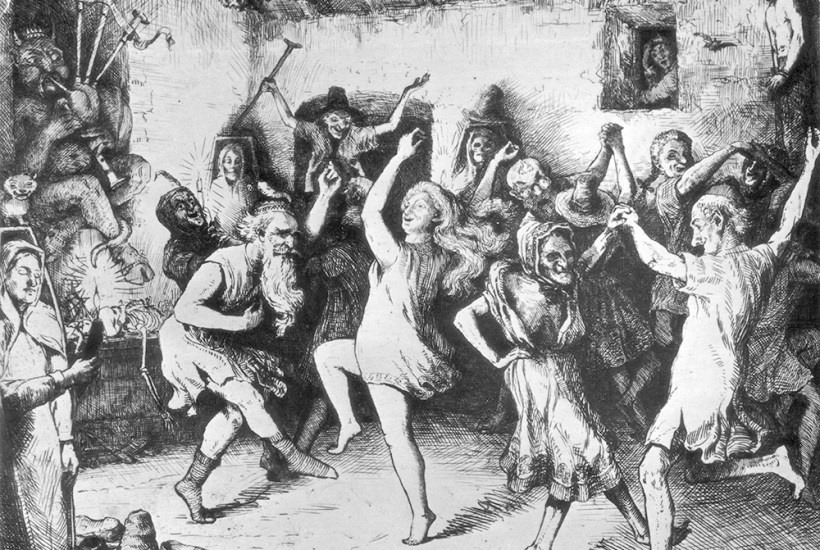

The museum’s exhibits are eclectic – from Crowley’s wand to mass-produced pin cushions for sticking pins into the Kaiser’s arse to help the war effort. The creepiest items are those which were not so much collected, as offloaded on the museum – including a poppet (a doll representing a person for magical rituals) which ‘emitted such strongly negative energies’ that it was expelled from its previous museum. There’s also a weighing chair to weigh those suspected of witchcraft against a Bible, but it is sensibly chained to the ground to avoid any accidental modern witchfinding.

Boscastle is only 60 miles from Exeter, so I combine my trip with a visit to a conjuring show. Professor Brian Rappert, the conjuror-in-residence at Exeter Phoenix arts centre, is a sociologist whose main interest is deception, especially in the context of diplomacy and the security services. Next year, he will also be a lecturer on the magic course. The Phoenix’s marketing refers to what he does as ‘entertainment magic’, to distinguish it from magical magic – which, if unwieldy, is less twee than calling the latter ‘magick’, as Crowley did when he wished to emphasise he wasn’t doing children’s parties.

Brian’s is an extremely intimate show. He gathers half a dozen of us round a baize table, rolls up his sleeves and starts shuffling cards. The lights go down, and it feels even more like a seance. After each ‘effect’, as he calls them, he opens the conversation, seminar-like, to discuss the way in which our minds deceive us, or allow us to be deceived.

When I look down at the hand I have shuffled myself and see that he has somehow changed the order of the cards, it is more eerie than anything I saw at Zennor or Boscastle. Professor Rappert refuses to share the knowledge of how it is done. Maybe for that, you need to sign up to the course.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in