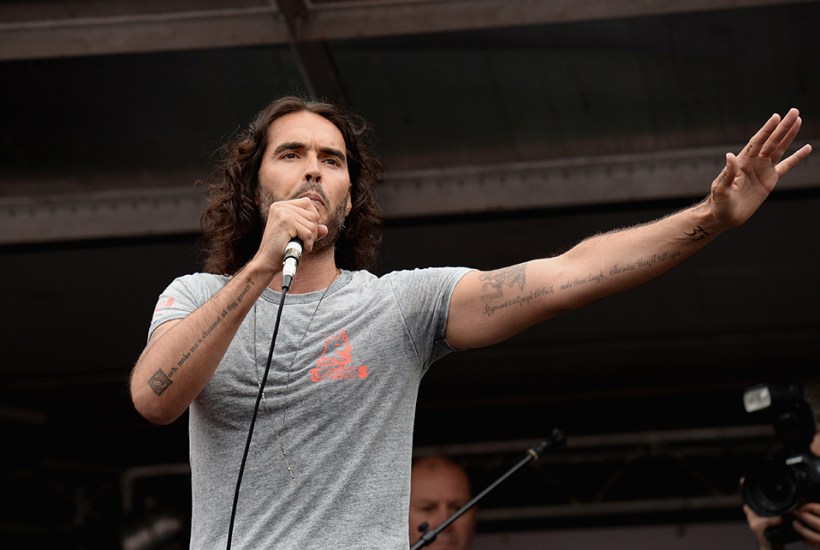

In 2014, Rolf Harris was convicted of sexual offences against girls. I wrote in this space that this would have represented more of a cultural change in the treatment of celebrities if he had been unmasked at the height of his fame. Current stars, I suggested, are much more rarely denounced: ‘I would not dream of suggesting that Russell Brand is a sex criminal, but we know, from his own account, that he has slept with a great many women.’ He had even, on his infamous Radio 2 show, boasted of sleeping with Andrew Sachs’s grand-daughter, yet ‘the BBC broadcast this as comedy’. ‘If the celebrity wheel of fortune ever went against Brand,’ I went on, ‘would it be surprising if some of the women decided to accuse him of “inappropriate” acts? Would the BBC then find the whole thing less funny?’ Nine years on, young Russell Brand is now 48. Has he been ‘called out’ because the culture has finally turned against the exploitation of young women by powerful men, or because he is now, by the cruel judgment of showbiz, a has-been?

This provokes reflection on the fate of Bernard Looney, the chief executive of BP, who has resigned. The formal reason, which presumably is genuine, is that Mr Looney had failed to be ‘fully transparent’ with the board about the full extent of his ‘personal relationships’ with staff members. Was another factor also in play? Mr Looney had won many plaudits for moving BP away from fossil fuels and into renewables. That trend was all the rage in the early days of net zero. But it was perilous to expose BP, a company made rich by oil and gas, to the intermittent power of wind. In February 2020, announcing his ‘new purpose and ambition for the company’, Mr Looney said, ‘We all want energy that is reliable and affordable, but that is no longer enough. It must also be cleaner. To deliver that, trillions of dollars will need to be invested in replumbing and rewiring the world’s energy system. It will require nothing short of reimagining energy as we know it.’ His reimagination began to get the better of him. Although BP had investments in Russia, he did not imagine the war in Ukraine. He also refused to imagine that reliable and affordable energy for all, and his company’s profits, might be badly damaged by the repudiation of fossil fuels. As reality supervened, the Looney tune began to sound less attractive. Therefore, fewer people were willing to catch him if he slipped. We shall see more such falls, because many of the business propositions net zero involves are not, to use a word its adherents love, sustainable. This week, Rishi Sunak has at last recognised the political version of this truth.

After the alleged infiltration of the China Research Group in parliament, it is being suggested that parliamentary visitor passes should be issued only after security background checks. Apparently, one suspect sometimes got in on a visitor pass. For practical reasons, however, this is a mad idea. All visitors to parliament already undergo bag and coat checks. If they had to wait for background checks as well, the system would grind to a halt. Besides, there is an objection of principle. The clue is in the name ‘House of Commons’. The ‘Commons’ mean everybody. Everyone has a right to visit. It would be extraordinary if the people were barred from the parliament that governs in their name, or even if a parliamentary authority, such as the Speaker, were to select who could enter. The public can seek out MPs in the Central Lobby (hence the right to ‘lobby’) and queue for seats in the public gallery. If the Commons had a central list of all the visitors it admitted, this would be information which could be hacked or abused. Imagine, for example, if you were an exiled Hong Kong dissident wanting to see an MP. If you thought the organs of the Chinese Communist party could follow your movements, you would not come.

There seems no overwhelming reason why the doctors’ strikes – resuming as I write with what the ever-festive NHS calls ‘Christmas Day cover’ – should not go on indefinitely, now that the taboo has been broken and therefore professional standards have failed. My friend the frontline doctor writes, ‘A fair few docs are getting quite rich out of the strikes. Consultants can extract rates of up to £200 an hour to cover striking junior doctors.’ (This is possible because consultants’ and junior doctors’ strikes usually take place at different times.) He continues, ‘Those of us who are scabs sometimes get scab fatigue. I haven’t yet given in, but when you’re on a chaotic ward or two on your own and being abused by managers who know nothing about clinical priority, it is tempting not to turn up for the next day, just for a rest.’

Those British organisations trying to help Ukraine continue to get a dusty answer from the Charity Commission. These, they tell me, are some of the obstacles thrown in their way: 1) That the Foreign Office says no British passport holders should be in Ukraine, and that the Commission thinks small charities cannot keep their volunteers safe there. 2) That everything should be handled only by the big charities combined in the Disasters Emergency Committee. 3) That by taking vehicles (mostly field ambulances) and medical supplies to frontline areas, the volunteers become a ‘political’ organisation and not a charity because they are helping only one side in the war. 4) That by taking vehicles painted green, they are ‘military’ and thus political. Not all these objections are individually idiotic, but collectively they fail to recognise the reality of need and of war. One example: the Russians target white vehicles. Another: Ukraine is under martial law and so, in a sense, everything is run by the military. Surely the Charity Commission should accept that volunteers are happy to act at their own risk. Besides, some of those involved are charities it has recognised. Why is it trying to block others?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in