For a disconcertingly large constituency in Britain, Indian history ends in 1947.The two centuries leading up to that bloody year – when British rule formally ended, India gained independence and Pakistan was conjured into existence – were replete with books, articles, pamphlets, lectures and debates on India. What unites this body of work, apart from colonial condescension, is an effort to comprehend India. That impulse faded once India attained freedom.

Britain’s sins in India – racism, carnage, plunder – are a matter for British consciences. But a more confident India will also one day acknowledge that its modern state would have been improbable in the absence of the encounter with Britain. It was the British who, reacquainting Indians with their past glory, reminded them of their great and tragically squandered history. The Indian sociologist André Beteille, no apologist for empire, has written about the intellectual currents provoked by the public universities raised by the British in Kolkata, Chennai and Mumbai. They revolutionised for the better a society that had been frozen for centuries in a ‘conservative and hierarchical mould’.

After independence, India surged forward; Britain’s idea of India, however, remained captive to the past. India became the subject of conservative nostalgia – epitomised by interminable documentaries about the railways – and the object of progressive pity. India hands became a vanishingly rare breed in Britain. Now, as India emerges as an economic force and Narendra Modi’s sectarian Hindu revivalism displaces Pandit Nehru’s ecumenical secularism as the state’s de facto religion, Britain has barely anyone who can demystify this extraordinary transformation.

The all-pervading ignorance of India prompted British officials to make a series of self-wounding mistakes. The late Robin Cook, visiting Delhi in 1997, offered with an almost viceregal air to act as a mediator in Kashmir. His offer, clothed in casualness and hauteur, went down badly in a country then celebrating 50 years of independence. The almost inaudibly soft-spoken Inder Kumar Gujral, India’s prime minister at the time, told Cook that he was the emissary of a ‘third-rate power’ harbouring delusions of grandeur.

Tony Blair tried hard to mollify Delhi. Then, just over a decade later, Cook’s successor, David Miliband, nearly immolated the Anglo-Indian relationship by – as many Indians saw it – blaming India for provoking the attacks by Pakistani terrorists in Mumbai in 2008 in which more than 170 people were killed. Swapan Dasgupta, one of a tiny handful of unapologetically Anglophile figures in the Indian intelligentsia, called Miliband’s performance a gratuitous ‘assault on the geniality that has marked Indo-British relations’.

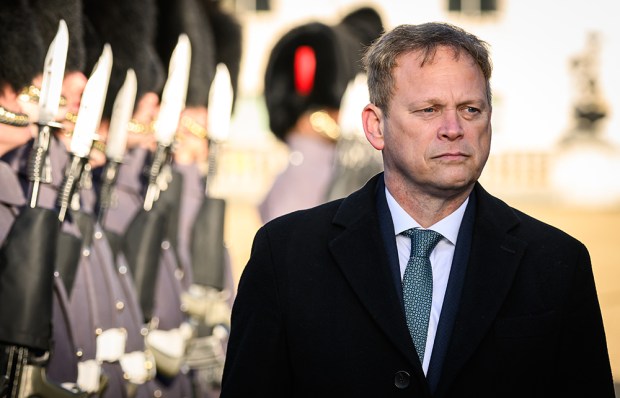

That low point in the bilateral relationship quickened the political reconfiguration under way in Britain. Labour, traditionally Delhi’s friend, drifted away from India. The Tories, who had oscillated between indifference and hostility during India’s decades of socialism and non-alignment, emerged as its ally. The Tory party started to view people of Indian descent as people, not projects, and politicians of Indian heritage rose rapidly through the party. Today the UK, led by a Tory PM of Indian ancestry, is pursuing a trade relationship that may shape Britain’s future following Brexit.

Just as Britain is reawakening to India, India’s democracy is deteriorating. How should Britain react? Be cautious, appreciate that Indian citizens alone can determine which way India goes, and discard the temptation to sermonise. Britain, the centre of the world for my parents’ generation and still the preferred destination for affluent Indians, no longer looms so large in the Indian imagination. Modi’s reactionary ‘New India’ will not abide another preening Miliband. And yet the relationship as it is unfolding between the two nations would have been inconceivable a few decades ago. We must hope Rishi Sunak’s tour of India is the beginning of a new era of informed, respectful, equal and comprehensive partnership.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in